Trillions of dollars move around in markets, and many of these flow through large asset management companies. To understand these stocks, and invest in them, requires understanding the basics of the industry and how asset management has undergone major changes lately.

One of the most obvious developments has been the move from active to passive strategies. Investors are increasingly adopting lower cost passive investment products like ETFs.

This shift to passive asset management has created pressure for some of the top publicly traded asset management companies today.

These more traditional asset managers include large companies like:

- $BLK – BlackRock

- $TROW – T. Rowe Price Group

- $BEN – Franklin Resources

- $IVZ – Invesco Ltd

Though the winds seem to be permanently shifting towards passive management, you can’t paint this industry with a broad brush and declare active asset management dead.

The truth of the matter is that there are an increasing variety of investment vehicles, and that asset management has so much more to do than just traditional actively managed mutual funds. The very diverse mix of clients extends past just your average Joe investors, and with their varying goals comes different needs and different solutions.

Better said—it’s not likely that asset management will ever go away.

And as some investors move away from the traditional stocks/ bonds portfolio and towards more exotic alternative options, there are a number of solutions from other top investment firms including:

- $BX – Blackstone

- $BAM – Brookfield Asset Management

- $KKR – KKR & Co

- $APO – Apollo Global Management

- $OWL – Blue Owl Capital

In each of these groups of asset management stocks there have been recent winners and losers; in this post we’ll cover the basic drivers of this industry, how some of the top players have been performing recently, and how investors can take advantage now and into the future.

The Basics of Asset Management

You can think of asset managers on a broad level as stewards of other people’s capital.

The definition of other people has a broad range—it can start as small as the average mom and pop investor, all the way to some of the largest institutions in the world. Institutions can include pension funds for firefighters and teachers, university endowment funds, insurance companies and so much more.

Because of the broad diversity of types of asset management clients, it’s important to get a basic sense of how the industry has traditionally and currently operates—especially before making any sort of judgments on the direction of the industry or the stocks within it.

The first term to understand for asset managers is AUM, or Assets Under Management.

In most forms of asset management, a manager will provide a product or service which directs the investment (or conservation) of those assets; the manager usually gets a (percentage) fee for delivering this.

So, AUM tends to drive revenues and profits for asset managers, as the larger the AUM the more income is generated just because fees are charged as a percentage of assets.

The next major metric for asset management companies is “net flows”.

The Net flows metric gives investors in these stocks a sense of how the organic growth of an asset management company is performing.

Asset managers have a variety of ways to grow AUM; one easy way is to acquire the assets from another manager (like a “regular” company would do M&A).

However, growing AUM from acquisitions might not be a good indicator of a company’s core business, as it could potentially mask from the real internal performance of the underlying assets being managed (and the ability of the manager to retain those).

There are a few main drivers which tend to influence AUM greatly:

- Investment performance (especially against a benchmark)

- Client sentiment (fearful or greedy)

- Client needs (liquidity or maximum growth of capital)

- Competitive forces (there are MANY).

Investment Performance

Investment performance tends to be measured against a benchmark because of the various risk/ return profiles of different types of investments and investment styles.

For example, stocks have traditionally outperformed bonds over the long term.

This intuitively makes sense because stockholders own an equity claim in a business, and get to participate in potentially unlimited upside from their claim on the business’s profits. Bondholders’ returns tend to be capped to the coupon payments if held to maturity, but they are safer than stocks in the case of default, as they have a priority claim (versus stockholders) on any remaining value of a bankrupted company.

Measuring the performance of an asset manager with a product or service which offers bond investments against the stock market would not be a fair comparison; underperforming stocks with a bond portfolio is not the sign of a bad manager.

Most investors intuitively know this, and so they tend to track an asset manager’s performance against its benchmark when making a decision of whether to join with or keep a particular manager.

Client Sentiment

One of the downsides of the asset management business is how income tends to fluctuate with the overall markets.

While many investors like to think of themselves as rational, when push comes to shove and markets fall into a temporary panic, some investors will pull their money out from the market even if it’s not the most beneficial thing to do for the long term performance of their portfolios.

Investors and institutions may switch from one manager to another if they perceive that their money is not being managed optimally; just as fear and greed can arise during different market cycles, so can fear of missing out affect an investor’s perseverance in an underperforming strategy.

Just as markets cycle, so does the relative outperformance and underperformance of different investment strategies.

Unfortunately, though people might understand this fact, they still might not act according to these principles for a variety of reasons—which can make retaining AUM for asset management companies difficult if the sentiment against their products/ services remains negative for an extended period of time.

Client Needs

One of the reasons that a client might withdraw the funds from an asset manager would be for reasons outside of chasing performance.

If an institution goes through a liquidity crunch (especially during tough market panics), they might need to withdraw their funds which were originally supposed to remain invested for the long term.

A retail investor might withdraw from a 401k, even if this is detrimental for long term performance, if they have a big, unexpected expense which comes up or they lose a job.

Or, an investor might decide that the portfolio needs to move more into fixed income instead of equities to reduce volatility; the fees for fixed income tend to be less than equities or some alternatives.

Competition in the Asset Management Industry

Finally, asset managers can (and have) come under intense competition from innovative products, services, or strategies which can reduce the long term AUM for even the best run companies.

A great example of this is the increasing demand for passive management instead of active management. Passive management tends to earn much lower fees than active does, and the continued pressure from this development has caused AUM fees to fall across the board.

More alternative asset management strategies such as private equity and real estate have put the pressure on traditional stocks and bonds managers—particularly those who offer higher fee mutual funds that are not meeting the changing demand from various kinds of investors.

From Active to Passive Asset Management

One of the vanguards which has driven the push towards passive management is the famous Vanguard and their offerings of ETFs which track major market indexes.

Vanguard is privately held as I write this, and so you can’t buy the stock of this tidal wave ETF giant.

However, other companies like Blackrock and T. Rowe Price have increasingly expanded their passive ETF offerings; other publicly traded companies have taken notice and are launching their own passive products/ solutions.

The pressure on AUM fees from the passive movement has not been trivial, and like I said already it has hit the rates across various investment types.

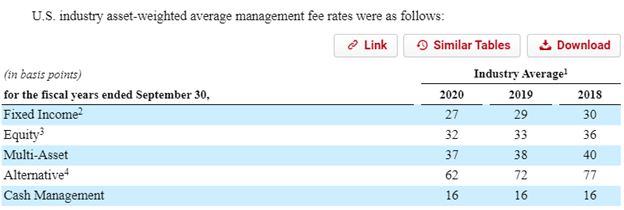

Publicly traded asset manager Franklin Resources disclosed in a recent 10-k the scope of these changes in the US:

If you’re buying the stock of a company you generally want to see pricing power; what all publicly traded asset management companies in the U.S. are seeing is exactly the opposite.

Small changes in basis points like these might seem like pennies on a dollar, but they really add up when it comes to the revenues generated from AUM. Even a 3 basis point (bps) move for multi-asset represents an almost -10% in fees from the same amount of AUM; this can be millions or billions of dollars for some asset management companies.

Note: Basis points are a way to present percentages. 100 basis points = 1%, so 27 basis points would be 0.27%.

Client Base and AUM Mix

Though the move to passive funds has created pressure on industry AUM fees, the extent to how this affects individual companies generally varies on a company-by-company basis.

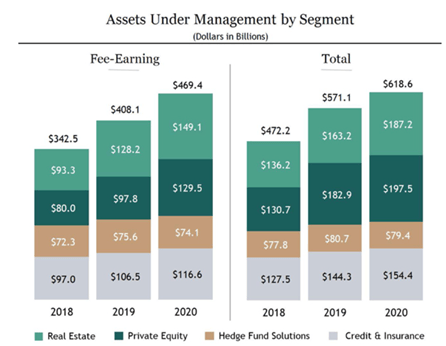

For example, Blackstone, which is currently the largest asset management company by market cap at $173B, divvies up their AUM by 4 major segments:

- Real Estate

- Private Equity

- Hedge Fund Solutions

- Credit & Insurance

Notice how different these services are compared to a traditional stocks and bonds manager. These solutions might see returns which drastically depart from the overall stock market, which can be a big part in why some of these are so attractive depending on a client’s needs.

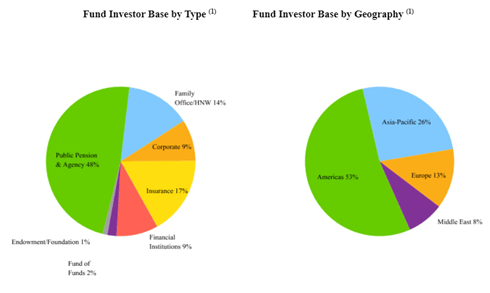

To speak on the variety of clients that an asset management stock might serve, here’s a description of the investor fund base for $KKR:

You can imagine how the goals and needs of an insurance company might greatly differ from a family office/ High Net Worth individual, and yet the asset manager companies drive AUM fees from both types of clients, which can make their revenue streams more diversified.

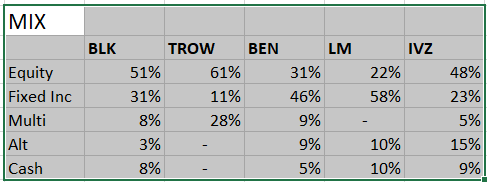

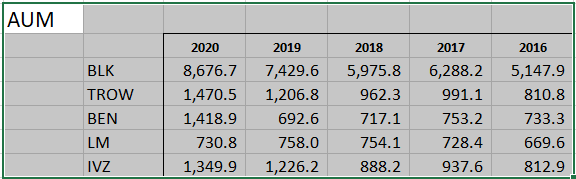

Traditional asset manager stocks see their AUM mix vary greatly even from these two examples; here’s a table I put together grouping some of the bigger publicly traded asset managers with more traditional mixes:

The extent of asset management doesn’t stop at traditional or alternative managers either; large banks such as Bank of New York Mellon ($BK) and State Street ($ST) have a large Private Banking focus and derive fees from the management of assets which tends to have a very personal touch for ultra high and high net worth individuals; contrast that to passive or active funds which can be simply purchased in the open market with zero touch or communication.

Evaluating Trends: AUM and Flows

There has been an interesting dichotomy in this industry over the last 5 years even just between the major traditional asset managers which I displayed above— $BLK, $TROW, $BEN, $LM, $IVZ.

First let’s look at Total AUM (in billions) for these 5 over the last 5 years.

I’d like to note that in 2020, Franklin Resources ($BEN) acquired Legg Mason ($LM), which is why you see the jump in AUM for $BEN from 2019 to 2020.

Note that the actual financial results from this merger were not fully reflected until the end of Fiscal Year 2021.

That’s right—those are 4 companies with AUM over $1 trillion.

These companies, especially Blackrock, can move the market.

The difference in the changes in Total AUM from year-to-year for this group is stark, to say the least. $BLK has been on a screaming tear, while $BEN and $LM have generally struggled.

But, remember how changes in AUM do not tell the whole story of how an asset manager’s core business might be performing. AUM fluctuates with market prices or foreign currency changes as it does with acquisitions; an asset manager with more AUM in equities will likely see revenues fluctuate more with the overall stock market than the average asset management company.

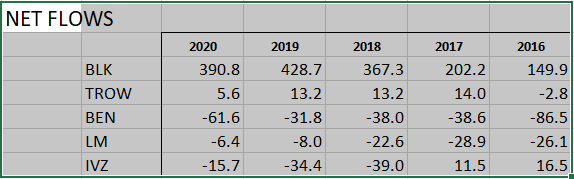

To get a better underlying idea of the demand for these asset managers from clients we need to compare the changes in net flow (in billions):

To really compare these apples-to-apples we’d want to combine changes in net flows with Total AUM to get percentage changes, but the same stark contrast remains between $BLK and $BEN, $LM, and even $IVZ.

Not only are these traditional asset management stocks seeing these declines in demand, but they’re also seeing those pressures on AUM fees which I talked about earlier; that’s double trouble which has contributed to a struggle in growing revenues for these companies (at least organically).

One final concerning note— $BEN and $LM have seen negative net flows for 8 and 6 consecutive years respectively, which shows a long term struggle and has definitely contributed to their weak stock performances in those periods.

Next Steps for Prospective Investors

Hopefully you’ve gotten a blueprint for how to evaluate asset management stocks and those companies in related industries on a basic level.

From here, you can go deeper into the various asset and client types and make a determination on how you see the futures of these various companies.

Like with any industry, the competitive forces are subject to constant changes and can have a big impact on the future profitability of these stocks.

That’s where doing a hard analysis on the competitive advantages of a company can be extraordinarily useful—after all, that was a major key to Warren Buffett’s success.

Related posts:

- Biofuel Industry Overview: Stocks to Watch (Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel) Some of the hottest renewable energy stocks which are working to fight climate change can be found in the biofuel, or biodiesel and renewable diesel,...

- Basic Overview of the G-SIBs Industry (U.S. Market) G-SIBs, or Globally Systemically Important Banks, comprise some of the biggest banks in the world and face additional regulations than smaller banks. They are called...

- BNPL Companies: Changing the Landscape of Payments Buy Now, Pay Later. The “new” payment scheme trend many analysts project will generate $100 million in sales in 2021. The buy now, pay later...

- How to Analyze Investment Banking Stocks: Understanding the Financials The oldest investment bank in the world, Berenbeg Bank, began in 1590 in Hamburg, Germany. And from there, the investment banking journey began. Recent incarnations...