Studying Warren Buffett’s past investments remains a great way to learn. Over the years, Buffett’s investments have changed, but not a ton. He still looks for great companies at a fair price, and one of his best investments that goes under the radar is his purchase of National Indemnity.

National Indemnity, an insurance provider, is one of the first companies he bought as the owner of Berkshire Hathaway.

This investment allowed him to generate a ton of cash, which he would use to great impact.

Buffett’s buy of National Indemnity, along with Geico and General Re, has helped propel Berkshire into the future. It has been 56 years since his investment which has helped transform Berkshire.

To put it mildly, Buffett has loved insurance companies since his first meeting with Geico back in the day. And even though Berkshire remains a huge conglomerate worth billions, insurance remains the heart and soul of Buffett’s business.

In today’s post, we will learn:

- Brief Overview of How Insurance Companies Make Money

- Why Warren Buffett Loves Insurance Companies

- Details Behind the Purchase of National Indemnity

- What We Can Learn From Buffett’s Purchase of National Indemnity

Okay, let’s dive in and learn more about Buffett’s purchase of National Indemnity.

Brief Overview of How Insurance Companies Make Money

Before we dive into Buffett’s investment in National Indemnity, we need to understand the insurance business.

Despite the scary terms and different financials, the insurance business is simple.

The simplest way to explain how insurance companies work: they bet on risk. They bet on the risk that you won’t crash your car or have a fire in your house. They bet they can take in more in premiums, our payments, than pay out in claims.

The basic idea which drives the insurance revenue model is a contract with an individual or company. The contract ensures the insurer will pay out a specified amount of money in the event of a loss. These events can include accidents, fires, illness, or death.

Insurance can come in different flavors, the most common being life and property/casualty.

In return for taking this risk, insurance companies receive regular monthly payments from their customers. These policies or contracts can cover life, home, auto, illness, business, or anything else.

At the center of all of this, insurance companies remain for profit. Their goal is to take in more in premiums than they pay out.

Insurance makes money based on two methods.

The first method is easy to understand. As Geico collects insurance premiums and our monthly car insurance bill, the less they pay for accidents, or claims, the more money they make.

Insurers who retain more of their premiums operate at an underwriting profit.

The insurance industry operates on the idea they will collect more in premiums than they pay out in claims. The combined ratio or metric is the one they use to measure these flows. Anything below 100% indicates a company operating at a profit.

The combined ratio measures the incurred losses or claims compared to premiums. If a company operates above 100%, it indicates they lose money. Over the years, Buffett’s combined ratio hovered near 90-95%, generating profits for Berkshire.

Here’s an example, let’s say Geico earned $5 billion in premiums last year and they paid out $4 billion in claims the same year. That would mean Geico earned a profit of $1 billion ($5 billion – $4 billion = $1 billion).

The second method includes investment income.

When an insurance company takes in premiums, they bet it will take years, if not decades, to pay a premium. During that lull, they will invest those premiums in the stock market, typically the bond market.

Most bonds include safer investments, such as corporate or government bonds. Leading the insurance industry has a large stake in the bond market.

While bond investments don’t generate huge equity-like returns but offer safer returns, they also offer liquidity if the company “needs” funds sooner rather than later.

Life insurance companies typically have a much higher proportion of fixed assets like bonds versus equities. Property & Casualty companies can have a larger portion of equities while still heavily invested in the bond market.

Now, here is where Buffett stands out from the crowd. Most of his insurance profits remain invested in equities like Apple, Coca-Cola, and American Express.

Why Warren Buffett Loves Insurance Companies

As mentioned above, most insurance companies invest their profits in bonds. Buffett takes a different approach; over the years, he has used the “float” from National Indemnity to invest in stocks and acquisitions.

So what is float?

It’s a term Buffett has made famous over the years, and he has used the float to generate wealth for himself and his shareholders.

Float is the money an insurer holds between when customers pay premiums and insurers pay out claims.

Here is Buffett explaining float:

“Insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. This collect-now, pay-later model leaves us holding large sums — money we call “float” — that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, we get to invest this float for Berkshire’s benefit.

If premiums exceed the total of expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income produced from the float. This combination allows us to enjoy the use of free money — and, better yet, get paid for holding it. Alas, the hope of this happy result attracts intense competition, so vigorous in most years as to cause the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Usually, this cost is fairly low, but in some catastrophe-ridden years, the cost from underwriting losses more than eats up the income derived from the use of float.”

Buffett LOVES the idea of insurance float because he gets to invest with other people’s money.

As an insurance business grows, so does the float. Think about the growth of Geico over the years; that growth has led to growth in Berkshire’s float. All those commercials with the little green gecko have helped grow Berkshire’s float over the years.

The growing moat means Buffett has more money to invest and acquire companies.

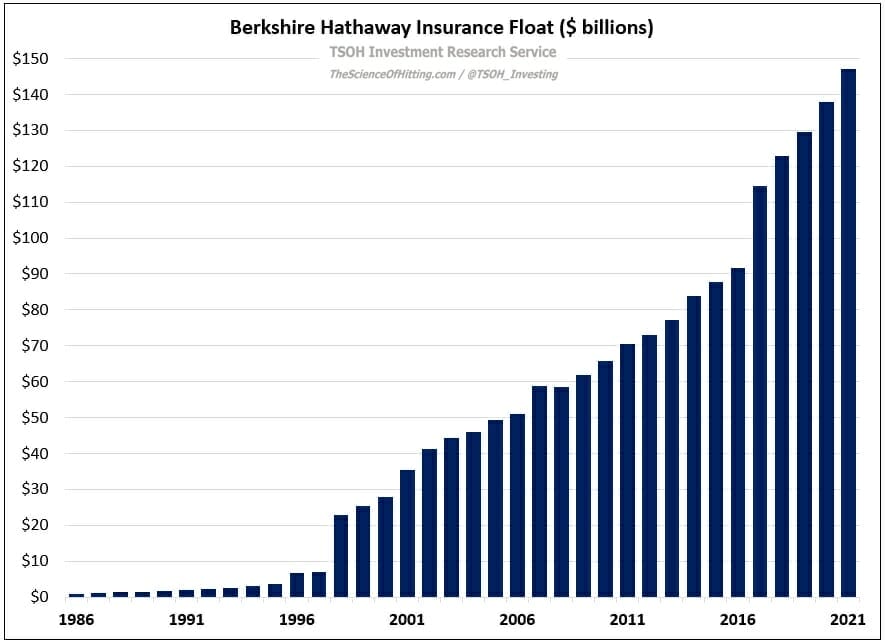

Berkshire’s float has grown from $19 million in 1967 to 2021’s level of $147 billion.

That’s a lot of play money for Buffett to work his magic. And it helps explain why he believes his 1967 investment in National Indemnity helped propel Berkshire.

Details Behind the Purchase of National Indemnity

Before we discuss the purchase of National Indemnity, let’s look at how Berkshire appeared in the middle to late 1960s.

Berkshire was a struggling, capital-intensive textile business when Buffett took over in 1966. One of Buffett’s first objectives was optimizing the company’s overhead costs, capital expenditures, and working capital requirements.

He could free up money to buy investments or acquisitions by focusing on these objectives.

The financial state of Berkshire in 1966 was the following.

The net income from the textile industry was roughly $2.6 million in 1966, while the realized gains from the investment portfolio were about $166,000. In 1966, Berkshire had a free cash flow of around $5 million. The textile industry lost money in 1967 to the tune of roughly $1.3 million.

So, not in great shape.

Enter National Indemnity, which, once acquired, helped stabilize net income and provide funds for investment.

So who was National Indemnity, and why or how were they on Buffett’s radar?

National Indemnity was a property/casualty insurer founded in 1940 by Jack Ringwalt. Along with National Indemnity, he had an affiliate called National Fire & Marine Insurance Company.

Here are a few fun facts about the world’s events during 1967, the time of the acquisition.

- The Beatles released “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”

- The confirmation of Thurgood Marshall as the first African American Supreme Court Justice

- The average American earned $7.3k a year.

Throughout National Indemnity, a familiar face from Warren Buffett’s early days reappears.

Jack Ringwalt, the company’s private owner, was the same Omaha businessman who had declined Buffett’s initial offer to invest $50,000 in his investing partnership.

Ringwalt’s company covered risks that were challenging to value, and his company’s catchphrase was “There are no bad risks, only bad prices.” People who knew Ringwalt said he had been quite successful in business and was only prepared to sell once or twice a year, usually when he was particularly unhappy about something.

Early in 1967, Buffett reportedly learned that Ringwalt was in one of these moods via a mutual acquaintance.

As told by Alice Schroeder in Snowball, the story was Buffett was looking for some help at Berkshire. He was looking for a company to offset the poor returns at Berkshire. He was also looking for opportunities to invest Berkshire’s cash flow into steadier businesses.

Buffett saw something promising in National Indemnity, which began in 1941 as an insurer for taxi liability insurance. The company focused on specialty insurance and, over the years, had become broader in scope.

What set National Indemnity apart was Ringwalt’s business ideas.

The foundational idea of National Indemnity was that there was a good premium for any valid risk, and the insurer’s main goal was always to make the right judgment and generate an underwriting profit. The company was prepared to cover risks like casualty for long-haul trucks, taxis, and rental cars, unlike typical auto insurers at the time. In contrast to its competitors, National Indemnity did not pursue revenues when they would not be lucrative at the underwriting level. Another essential component of sound management at National Indemnity was this capital discipline.

Buffett loved the fact National Indemnity managed its business with profits as the main goal, as opposed to growing as fast as they could.

In 1967, National Indemnity earned $1.6 million in net income on $16.8 million in premiums. After the acquisition, they improved to $2.2 million in net income on $20 million in premiums.

Buffett valued the intangibles of the business and Jack Ringwalt greatly. He paid $8.6 million for the company, equaling at the time a 5.4 P/E ratio ($8.6 purchase price / $1.6 earnings).

Buffett had first offered $35 a share for the company, with Ringwalt countering at $50. Buffett agreed, and after a handshake, they finalized the deal.

During his 1968 Partnership Letter, he stated, “Everything was as advertised or better.“

What We Can Learn From Buffett’s Purchase of National Indemnity

Here is what Buffett thought when he made the National Indemnity acquisition.

Buffett paid $8.6 million for a company with a tangible net worth of $6.7 million. Buffett paid a premium of $1.9 million (28%) for an insurance business generating a combined ratio below 100% or a profitable company. He paid $6.7 million for $19.4 million in float, which he could invest in American Express or other businesses.

As he loved using “others” money, the idea that he paid $6.7 million to use the $19.4 million would have been quite the allure. He didn’t get to keep the float, but he did keep any dividends, interest income, or capital gains. And that is how he started building the Berkshire Hathaway we all know.

Buffett’s return on his investment over 50 years later? A cool 1,826,163%, which is not too shabby.

What can we learn from Buffett’s investment in National Indemnity?

- Buying a wonderful company at a fair price

- Looking beyond the earnings

- Finding companies who can raise capital and reinvest said capital at higher rates

All three of these ideas keep popping up in Buffett’s investments; you might say they represent a trend.

Buying National Indemnity wouldn’t qualify as expensive, based on its earnings. But Buffett was willing to pay a higher price because he saw the potential to reinvest the float for greater returns. After the success of his American Express investment in 1965, he was determined to find others in the same vein.

Buffett saw that National Indemnity could generate profits with their assets. Then they could reinvest those profits at higher rates. This, to him, was the “perfect” kind of investment, with low capital requirements and high returns on capital.

If you look at the history of his investments, from:

- See’s Candies

- Coca-Cola

- American Express

- Geico

- General Re

- Apple

These companies represent capital-light companies generating profits and free cash flow. All at high rates of return on capital, which helps create a flywheel to keep generating higher returns.

We can use this framework to help us find great companies selling at a fair price with great returns on capital. Simple, huh?

It sounds simple, but it’s not easy.

But ask yourself, what would you be willing to pay for certain companies if they generate great returns on capital over a long period?

Once you figure out the answer, you will find great companies to buy. Remember, you don’t have to swing at every pitch; you can wait for your pitch.

Investor Takeaway

Buffett used the acquisition of National Indemnity to pivot away from an unprofitable textile business to the giant company it remains today. The acquisition set the stage for transforming from a capital-intensive textile mill worth $20 million to the $696 billion titan of today.

Today, Berkshire has three main insurance businesses under its hood. The reinsurance business, General Re, and Geico, plus some smaller insurers, including National Indemnity.

Collectively, Berkshire’s insurance businesses have grown the insurance float from $19 million to $145 billion today, remarkable growth for such a big business. They have also grown their insurance business by an astonishing 74% since 2010.

Considering how much Buffett loves insurance and the float they generate, I wouldn’t be surprised to see it continue to grow for another 54 years.

The National Indemnity investment continued in the same vein as American Express. Find a profitable, cash-generating investment and pay a fair price for those assets. He continued to use the same investment process with Coca-Cola and Geico later.

It was a theme he would return to time and time again, and we can learn to find the same kind of investments if we do the work and spend the time learning his timeless lessons.

And with that, we will wrap up our discussion regarding Buffett’s acquisition of National Indemnity.

Thank you for reading today’s post; I hope you find something of value. If I can be of any further assistance, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Until next time, take care and be safe out there,

Dave

Sources:

https://einvestingforbeginners.com/invest-in-insurance-companies-daher/

https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2021ltr.pdf

https://enterprising-investor.com/national-indemnity-acquisition/

https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2021ltr.pdf

https://pragcap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/1968.01.24.pdf

Dave Ahern

Dave, a self-taught investor, empowers investors to start investing by demystifying the stock market.

Related posts:

- What We Can Learn From Warren Buffett’s Four Pillars of Investing Warren Buffett has covered every aspect of investing over the years. Whether in one of his letters to shareholders, an interview, or an essay, a...

- Warren Buffett’s Railroad Investment Updated 9/15/2023 2007, Warren Buffett revealed he had bought over 60 million shares in Berkshire’s first railroad. Buffett continues as our generation’s greatest investor. And...

- What is Minority Interest and How Do I Find It? Acquisitions, as a part of growth, continue to play a role in the markets. Many companies use this strategy. Berkshire Hathaway, Google, and Constellation Software...

- Evaluating Management with a Simple Checklist for Investors “When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that...