Post updated: 9/07/2023

When it comes to projecting or estimating future free cash flow growth, there isn’t a strict science behind it. Some common methods involve ROE and retention ratio, for example.

While using traditional methods to estimate future free cash flow growth can help for a ballpark projection, this can be inaccurate for many reasons. We will discuss some of these today, including:

- The Traditional Methods of Estimating Growth

- How Capital Allocation Drives FCF Growth

- Industry Maturation and Free Cash Flow

- Real-Life Example: Shutterstock

- Estimating Future Free Cash Flow Growth (Example)

Alright, grab a coffee and let’s dive in.

The Traditional Methods of Estimating Growth

First, let’s examine some of the most common and useful ways to numerically estimate future free cash flow growth:

- ROE and Retention ratio

- ROIC and Investment rate

- Historical growth

- Relative (essentially matching competitor’s historical growth)

I highly recommend you give yourself an in-depth education on these methods with the articles linked below.

As a very superficial summary, here’s the formulas for each of the main methods:

- ROE and Retention ratio

- Estimated growth rate = ROE x Retention ratio

- Where, retention ratio = percentage of earnings not distributed by dividends and share repurchases

- ROIC and Investment rate

- Estimated growth rate = ROIC x Investment rate

- Where, investment rate = percentage of free cash flow not distributed by dividends and share repurchases

- Historical growth

- Examining financial statements and recording the growth in FCF/ share or EPS over a selected time period

- Relative to competitors’ growth

- Same process as historical growth, but measuring competitors’ financial statements

You’ll notice that each of these factors rely on historical data, which makes sense because historical data is the only reliable picture we can paint about a company’s performance (unless you have a crystal ball).

But, blind use of this data to estimate future free cash flow growth can be detrimental to an investor’s results because there are many other factors that can change the course of a business’s ability to create profits.

These can include:

- New competitors entering high-margin markets and reducing future margins

- Current or new competitors creating a more valuable product or service

- Industry consolidation creating stronger competitors

- Changes in consumer preferences and behaviors changing demand or profitability

- Changes in the macroeconomic picture, or regulation, or a myriad of other factors leading to an industry becoming less (or more) profitable, having a higher (or lower) growth in revenues potential, etc

That’s not to say that investors are hopeless, or that we have to spend thousands of hours on every investment idea to think of every possible factor in the future.

But that is to say that we need to adjust our valuation models.

We can do this by requiring a higher margin of safety. Especially when there seems to be many more outside factors than an investor might want.

Let’s take one historical example of a factor that influenced free cash flow growth, but on the positive side. And then, we’ll look at a real-life example.

How Capital Allocation Drives FCF Growth

Since Buffett is the king of free cash flow (what he calls owner’s earnings), let’s break down the types of businesses he likes investing in.

Obviously, he likes the businesses with a superior competitive moat and great growth—like Coca-Cola, American Express, and GEICO. But he’s also quite happy to invest in cash flow cows, businesses that aren’t necessarily the best or the fastest growing but require very little capital to spit out high amounts of free cash flow—See’s Candies and Dairy Queen are just examples.

See’s Candies doesn’t need to invest heavily in new technology. They don’t really need to spend much on marketing, since their brand name is so strong.

Instead, See’s Candies spits out great free cash year after year as customers consume their chocolates for the holidays and Valentine’s Day. Buffett uses that free cash flow to invest in other businesses.

Of course, See’s Candies probably had to reinvest heavily in its own business at the start to grow and scale. But at a certain point the company felt like it grew enough, and then funneled those profits back to its owners rather than to expand continuously. This is evident by the fact that See’s Candies has historically been a West Coast brand, and has a muted mall presence around the country.

Rather than battle it out for global supremacy, See’s happily sold to Buffett, who has happily let See stay in their niche while re-allocating those profits elsewhere.

It’s that inflection point where I want to focus today.

At a certain point, a company has to decide whether to heavily reinvest free cash flows into the business to continue to aggressively grow…

Or, dial down the free cash flow reinvestment and continually return much of that cash back to shareholders (these days, it’s more aggressively done through share repurchases rather than dividends).

Industry Maturation and Free Cash Flow

Really at the end of the day, it all comes down to industry maturation.

In a great piece about life cycles of an industry, Cameron Smith revealed the 5 major stages of an industry’s life, which can be applied to individual businesses as well:

- EMBRYONIC Stage

- GROWTH Stage

- SHAKEOUT Stage

- MATURE Stage

- DECLINE Stage

Essentially, there is exponential growth for a market until the SHAKEOUT stage, at which point demand for the industry’s products and services begins to slow and stops its exponential trend.

Valuations start to compress back to the more rational values here, and the difference between the strong and the weak competitors finally becomes evident.

As this evolves into the MATURITY stage, which as Cameron states is hopefully the longest and most fruitful for companies and investors, the efficiency of an industry really hits the inflection point and businesses have a fundamental decision.

Should they (1) stay a free cash flow cow, (2) find attractive opportunities in a new market, or (3) destroy shareholder value?

In situation 2, if the company can intelligently find a great new market to funnel free cash into to maintain its historical growth (and ROE and ROIC), then those free cash flow growth formulas work well in projecting its future.

In situation 3, which can be a by-product of a failure of situation 2, traditional free cash flow growth projections won’t work so well in identifying the company’s true performance, as new capital is invested at rates that return less in future growth than when the industry was younger.

Let’s dive into a company’s financial statements to try and identify situation 1, where a company decides to just stay a cash cow.

Real-Life Example: Shutterstock

I want to examine a small business in a small niche market, Shutterstock ($SSTK). This is a company that provides paid stock photos, which businesses and consumers use to remain copyright complaint on blog posts, videos, and other commercial use or personal use material.

This industry is interesting because most of the players work on an almost “Uber” model for stock photos.

Basically, contractors can submit their own photographs, and businesses and consumers purchase the rights to these photographs, with a website like Shutterstock simply providing the marketplace for it.

More on that in a bit, let’s see why I identified this company as possibly at an inflection point for FCF.

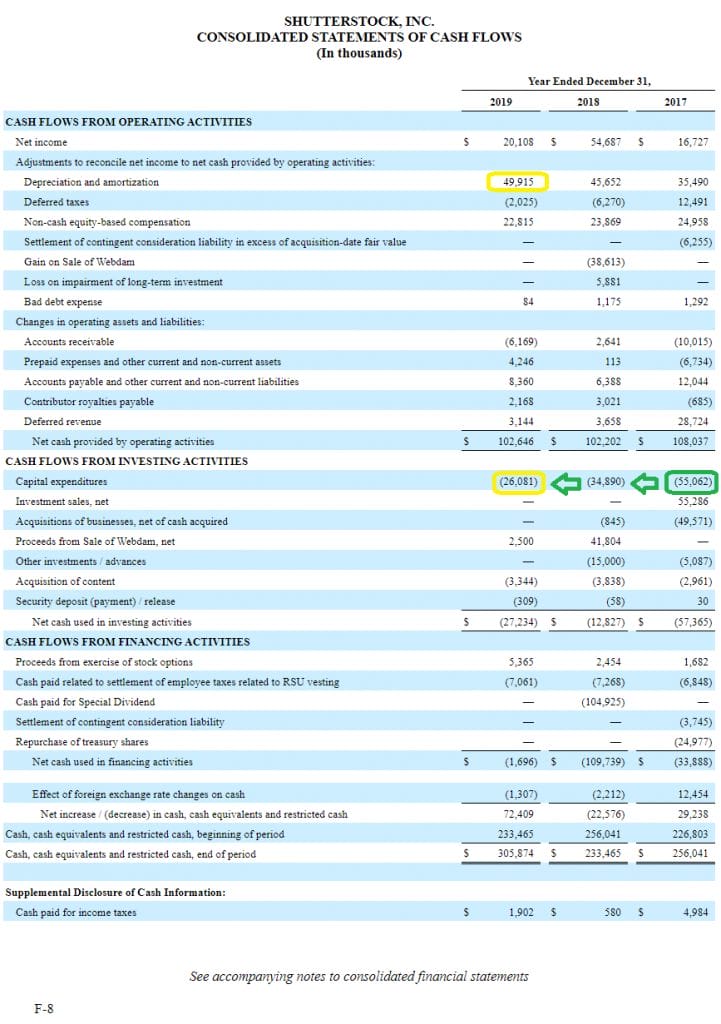

Taking the company’s 10-k filed in February 2020, their cash flow statement reported the following:

Notice the two trends here. We have Capital Expenditures that are significantly lower than Depreciation and Amortization in 2019, and rapidly declining Capital Expenditures from 2017 to 2019.

Cash from operating activities are basically flat from 2017 through 2019, but a rough estimate of FCF (CFFO minus Capex) shows a free cash flow growth rate of 27% in 2018 and 13.7% in 2019.

Note that shares outstanding has been flat in this same period, so we can substitute FCF for FCF/share.

The next question becomes, what has the company done with this unlocked FCF?

There was a special dividend in 2018 of $104m, so that looks like the big capital allocation over the last 3 years.

Since historical Depreciation and Amortization has been between $35m and $49m, and Capex has decreased from $55m to $34.9m to $26m, that’s an extra $40m or so in free cash flow which the company unlocked simply by lowering their capital expenditures (evolving to a cash cow).

This begs another question:

- Is management dropping the ball by not getting aggressive to reinvest in future growth?

- Or, has management identified that their industry is in the MATURITY stage and will stay there?

That takes us back to evaluating the industry itself and where it is in its life cycle, which is where an investor’s circle of competence comes in.

Estimating Future FCF Growth (Example)

Let’s gather what we know and can reasonably assume.

We know that competitors will grow and attempt to steal market share.

- How Shutterstock handles this threat depends on its competitive advantage (or lack of).

We know that the company will see growth from inflation and the growth of the market without doing anything, if it maintains its market share.

- Companies will always need copyright-compliant materials

- We know that the number of U.S. businesses will grow every year

- We know that as inflation rises, so do most products and services

The market looks small enough to not make a drop in the bucket for most big companies.

- $650m in revenue for our leader SSTK

- Industry with mostly private companies should make it hard for an outsider to aggressively acquire a large majority of this market

The industry is commodity-like. Taking market share has traditionally been hard.

- Outside of dramatically lowering prices and/or making a massive push in marketing spend, stealing considerable market share appears difficult

- Companies still need stock photos and can shop around willingly

- Unsplash.com is trying the free model but its website’s performance hasn’t been trending in a good direction lately

With that all said, let’s develop a free cash flow growth estimate, based on 2017-2020 financials.

Looking at the company’s 10-q filed October 2020, the company has spent $20m on Capital Expenditures through the first 9 months of the year, which compares with the almost $19m spent in the first 9 months of 2019.

So, it appears that we might’ve found the matured (annual) maintenance capex for this cash cow, the same ~$25m spent for capex in 2019.

Noting that revenue growth for the company over the last 2 years has been 4% and 11% respectively, and the CFFO (cash from operating activities) has been flat due mainly to extraneous transactions like changes in working capital and taxes and a divesture, I think a revenue growth estimate for the future could fall in the 4%-6%.

Let’s say that 2%-3% comes from growth of the number of businesses and 2%-3% from inflation.

This should flow smoothly down to free cash flow unless there are any crippling risk factors to those margins (like industry disruption).

There could be some margin improvements here or there, but in general I like to stay conservative and generally won’t add those to a free cash flow growth estimate.

However…

This all assumes that Shutterstock can thwart its major disruptive threats; today (as of September 9, 2023), it appears that A.I. could be a huge threat to the company’s business model.

In that case, if a competitor (AI-based or not), takes significant market share, then the matured industry growth dynamics we’ve estimated above probably won’t happen. The actual results could be much, much worse.

Investor Takeaway

I hope that helps provide clarity on projecting future free cash flow growth for a company in a matured industry.

There’s definitely potential of finding gems with this approach, where the substantial increase to free cash flows from a transition to maintenance capex at an inflection point of the business has not been baked into estimates yet.

For ideas on when that could happen, I recommend reading Dave Ahern’s article on calculating maintenance capex through a few formulas. Or, you could additionally find maintenance capex from a company’s 10-k if they make the distinction explicit.

Either way, it comes back to Warren Buffett’s owner’s earnings, and perhaps provides great clarity on why his free cash flow estimates are different than the traditional definition—where he’s dividing capex into maintenance capex and growth capex.

By valuing companies on their probable maintenance capex rather than total capex, you get to participate in the company’s substantial free cash flow growth once they hit the inflection point of reducing total capex spend.

A fantastic unlock of value, for both the company and the investor, as long as the industry conditions are right.

Andrew Sather

Andrew has always believed that average investors have so much potential to build wealth, through the power of patience, a long-term mindset, and compound interest.

Related posts:

- Understanding AFFO for REITs: The REIT Equivalent of Free Cash Flow Estimating a valuation for a REIT is vastly different than a valuation for any other company because of the unique business model for REITs. That’s...

- Making a 3-Variable DCF Sensitivity Analysis in Excel A DCF sensitivity analysis is a fantastic way to estimate valuation on a company because it gives you a range of intrinsic values instead of...

- Building a DCF Using the Unlevered Free Cash Flow Formula (FCFF) Updated 12/12/2023 “Intrinsic value can be defined simply: It is the discounted value of the cash that can be taken out of a business during...

- Using 65 Years of Statistics to Make an Intelligent Cash Flow Projection In valuation, the name of the game is expected future cash flows. It’s not about the past, it’s about the future. So in trying to...