Investors fortunate enough to see the share price of an investment increase up to their calculated intrinsic value are then faced with the hard dilemma of whether they should sell and lock in profits, or, hold on and let the stock ride. This article will discuss the company and tax analysis that investors should carry out as they make the decision to lock in profits or let it ride.

Update the Intrinsic Value Calculation

First and foremost the initial intrinsic value calculation and investment thesis should be revisited. Depending on how long the investment has been held, the business and its intrinsic value could have changed materially. It is important to get an up-to-date valuation of the business before making a decision.

The IFB Equity Model spreadsheet can be used to get a sense of valuation and allows users to play around with the operating expenses of the company and revenue growth (or decline!) rates. This model is one of the courses and spreadsheets available on the IFB products page and allows users to easily value a company in a fully customizable model using six different techniques which grabs data automatically from forecasted 10-year financial statements.

What Kind of Company Did I Invest In?

The next question to ask one’s self is what kind of company did I invest in? Depending on whether the investment was made in a distressed, mediocre, or great company can have wildly different implications on future growth in the intrinsic value of the business and whether or not to sell the company. We can refer back to return on invested capital (ROIC) analysis to evaluate what type of company we are invested in and what the further growth implications might be.

Distressed Company: The original investment was probably made because the company was trading well below intrinsic value or net asset value and is what the Warren Buffet would refer to as the “cigar butt” investing style practiced by the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham.

By distressed, we are talking about a company whose ROIC is lower than an economical 6-9% range and it is not able to consistently earn its cost of capital. This company is likely distressed and struggling to meet its sustainable capital expenditure needs, let alone grow the business.

As the company has little hope of growing, let alone surviving, the investment SHOULD BE SOLD when it reaches intrinsic value or net asset value and the investor can move on to finding the next “cigar butt” to hold for a little while.

Mediocre Company: The original investment was probably made because the company looked relatively cheap and offered a superior earnings yield to other investment options considered. By mediocre company, we are referring to a business which is able to earn its cost of capital with a return of capital around 6-9%. The business should be able to continue operating as a going concern and grow alongside the broader economy. As such, investors should feel comfortable adding a growth rate of long-term potential GDP growth (say 3%) on top of the earnings yield.

As the company should continue as a going concern, and hopefully grow along with the economy, the investment CAN BE HELD even when it reaches intrinsic value.

That being said, when holding a mediocre company, the investor should once again look at other potential investments to see if a superior earnings yield plus growth rate, or discount to intrinsic value, can be found. Always keep in mind taxes as will be discussed in the next section.

Great Company: When we talk about great companies, we are referring to companies that are able to earn a ROIC well above their cost of capital which as a rule of thumb means earning ROIC above that 6-9% range. A great company is able to earn such a return by having what Warren Buffett refers to as an “economic moat” that the industry competition is not able to replicate.

By being able to earn a ROIC above the cost of capital, a great company will be able to continue to grow the intrinsic value of the business above the rate of inflation by using the excess returns to invest in growth projects. These growth projects can take the form of investing in new assets to expand the business but could also simply be the company repurchasing/investing in their own shares because that “economic moat” is hard to replicate. Investors should feel comfortable adding a reasonable growth rate above 3% on top of a great company’s earnings yield.

Great companies SHOULD BE HELD as their intrinsic value could be constantly growing at a rate above GDP growth. It is a rare opportunity to buy great companies at favorable prices and investors should let this opportunity compound tax-free.

Warren Buffett’s 1988 investment in Coke would be a great example of letting an investment in a great company ride long-term and continue to compound as Berkshire continues to hold their treasured Coke shares to this day over 30 years later.

Take into Account Capital Gains Tax

As the famous quote from Benjamin Franklin goes,

“Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”

While investors cannot avoid paying taxes, we can certainly try to delay paying them.

Depending what type of account an investment is held in, taxes can have large implications in the decision making process of whether to sell or hold an investment. The larger the profits from the investment, the larger the capital gains tax that needs to be paid. This means that when an investor is thinking about selling an investment with a certain earnings yield or discount to intrinsic value for a relatively better one, they need to be sure they COMPARE THE NEXT INVESTMENT IN TERMS OF AFTER-TAX DOLLARS that will be invested.

While each investors tax situation is different based on country tax codes and personal marginal tax rates, we will use some generic tax rates as an example to get the point across. Investors should look at their own country’s tax code and personal marginal tax rates to develop their own tax analysis.

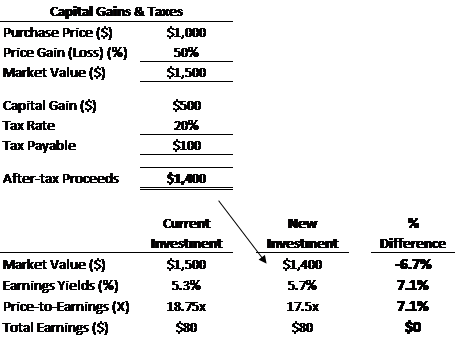

As example, let’s imagine an investment that was originally purchased at an 8% earnings yield (12.5x P/E). Given the investor’s country and personal tax bracket, their capital gains are taxable at 20% (approximate maximum rate for long-term U.S. investments held over 1 year). After two years, the investment has now increased to trade at a 5.3% earnings yield (18.75x P/E) and at a price that the investor calculates to be the company’s intrinsic value. At what valuation would the investor be indifferent between selling their shares for a new investment or continuing to hold on to the current investment?

The first step is to determine what after tax proceeds can be invested into a new investment. As calculated below, in this scenario, there would be $100 tax payable on the $500 capital gain meaning that only $1,400 will be able to be invested in a new stock. This means that in order to keep the dollar amount of earnings the same, the new investment would need to trade at a valuation that is 7.1% cheaper which in this case would be an earnings yield that is a least 5.7% for a P/E ratio of 17.5x.

While this 7.1% difference might not seem huge, it is enough to effect the decision making process. The bigger the percentage capital gains, the bigger this difference will be. In Warren Buffett’s case with Coke, the share price has increased around 1,750% since Berkshire’s initial investment which would make taxes a huge consideration in the decision to continue to let it ride!

Related posts:

- How to Find the ADR Dividend Tax Policy of a Company in Minutes An ADR, or American Depositary Receipt, is a simple type of share that allows U.S. investors to invest in companies headquartered outside the U.S. But...

- Capital Gains Tax Calculator for Relative Value Investing Turnover of investment holdings is a natural occurrence in any portfolio that triggers realized capital gains and taxes, which can eat into a portfolio’s return....

- How Do Dividends in a Roth IRA Work? What about REITs, MLPs, or ADRs? When I first learned about Roth IRAs, I thought the whole point of them was to eliminate taxes. Well, in essence, pay the taxes first...

- Qualified Dividends are Your Way to Minimize Tax on Reinvested Dividends! Long story, short, the answer is yes – you are going to have to pay taxes on reinvested dividends. While there are a ton of...