“It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

-Warren Buffett

Many investors use the above Warren Buffett quotation to describe his investment approach. Buffett now emphasizes investing in high-quality firms and has since stopped purchasing inexpensive, unloved enterprises.

He emphasizes his willingness to pay a reasonable amount for them because he knows that exceptional enterprises rarely sell for low prices. What does he mean by fair, though?

As Charlie Munger, his longtime business colleague, has noted, paying too much for a high-quality company might result in a bad investment. So how do investors find the ideal balance between price and quality?

Quality company share prices have risen significantly in recent years. The rising prices have contributed to the stellar returns of well-known fund managers such as Terry Smith and Nick Sleep.

Both invest in a concentrated portfolio of high-quality companies (less than 30 shares) and hold them for an extended period, joining Buffett as successful long-term buy-and-hold quality investors.

In today’s post, we will learn:

- What is a Quality Stock?

- Why Pay Up for Quality Stocks?

- What Does a Quality Company Look Like?

- Example of a Quality Company Selling for a High Price

- Investor Takeaway

Okay, let’s dive in and learn more about paying up for quality companies.

What is a Quality Stock?

The most ambiguous factor in the world of investment may be quality. There is no unified description for it, and there is no universal agreement that it truly stands alone.

Furthermore, it lacks the explanation for the presence and permanence of the value factor, which is the risk story, fundamental economic intuition, and easily observable behavioral underpinnings.

What is Quality?

Depending on who you ask, there are several answers to this question:

- Measures of profitability, such as gross margins, return on equity, return on invested capital, and stability, such as earnings variability.

- Growth, such as earnings growth or dividend growth, and financial health, such as debt/equity ratios, are common criteria asset managers and index providers use to define quality stocks.

High-quality businesses often have strong balance sheets, are continuously profitable, and continue expanding.

Many companies Buffett and Munger have held over the years fall into the category of quality companies they bought for a higher price.

Coca-Cola, Costco, Visa, and Gillette fall into this category.

During his 1996 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter, he stated:

“Companies such as Coca-Cola and Gillette might well be labeled “The Inevitables.” Forecasters may differ a bit in their predictions of exactly how much soft drink or shaving-equipment business these companies will be doing in ten or twenty years.

Nor is our talk of inevitability meant to play down the vital work that these companies must continue to carry out, in such areas as manufacturing, distribution, packaging, and product innovation. In the end, however, no sensible observer – not even these companies’ most vigorous competitors, assuming they are assessing the matter honestly – questions that Coke and Gillette will dominate their fields worldwide for an investment lifetime. Indeed, their dominance will probably strengthen.

Both companies have significantly expanded their already huge shares of market during the past ten years, and all signs point to their repeating that performance in the next decade.”

Why Pay Up for Quality Stocks?

Buffett’s famous phrase from the 1989 Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders gives us an apt description of quality: wonderful companies at a fair price.

Before the last two major market downturns in 2000 and 2007-2009, quality companies operated at their lowest prices at the height of the Internet bubble and the prelude to the Great Financial Crisis.

After the markets fell, the prices of quality companies rose as investors fled to quality.

It is crucial to consider how much we might pay for high-quality stocks. Although quality remains important, perhaps price is more crucial.

The biggest advantage investors gain from buying quality companies at a fair price remains the ability to compound over long periods.

Compounding growth is a quality company’s key to long-term better rates of return while limiting downside risk and creating shareholder wealth. The difficulty for investors is that only a small percentage of the hundreds of publicly traded companies on the world’s markets can regularly compound profits while offering some capital preservation in uncertain economic or market environments.

When a business has a sustainable ROIC due to recurrent sales that produce high gross margins with little capital intensity, it has the potential to be a “compounder.”

Compounders build with pricing power to safeguard their profits as expenses rise and recurring revenues to support sales volume on dominant and long-lasting intangible assets.

Compounders frequently outperform other businesses during economic downturns because of this. As a result of their consistent operational cash flow and lack of excessive borrowing, their profits are less reliant on cyclical factors.

For example, Visa, one of the leading global payment companies, has returned an 18.1% CAGR over the last ten years. But the company has traded above a P/E of 20 over the entire period, even reaching 40 P/E over the last few years.

Would you pay a higher multiple or valuation for an 18.1% return over the past ten years, considering coming off the last recession and a global pandemic?

Costco, the leading retailer, has returned 17.1% CAGR over the last ten years while trading above 30 P/E the entire time.

The above examples offer two great companies that have given shareholders great returns over the past ten years while trading at “higher” prices.

But, price does matter because companies such as Cisco and Microsoft took many years to return to their former glory. For example, Cisco, once the largest market company in the U.S. before 2000, has still not returned to those levels 22 years later. And Microsoft took 13 years to return to its former levels.

Holding through those periods would have been tough; I honestly don’t think I could have done it.

So, we can’t buy any old company; we need a framework to determine which companies offer quality at a fair price. As Buffett has mentioned before, we must understand valuation before starting to invest.

What Does a Quality Company Look Like?

Let’s create a checklist to help us find quality companies at a fair price. We will use a variety of metrics and models to help us find these diamonds.

Here we go:

- High gross margins > 50%

- Returns on equity > 15%

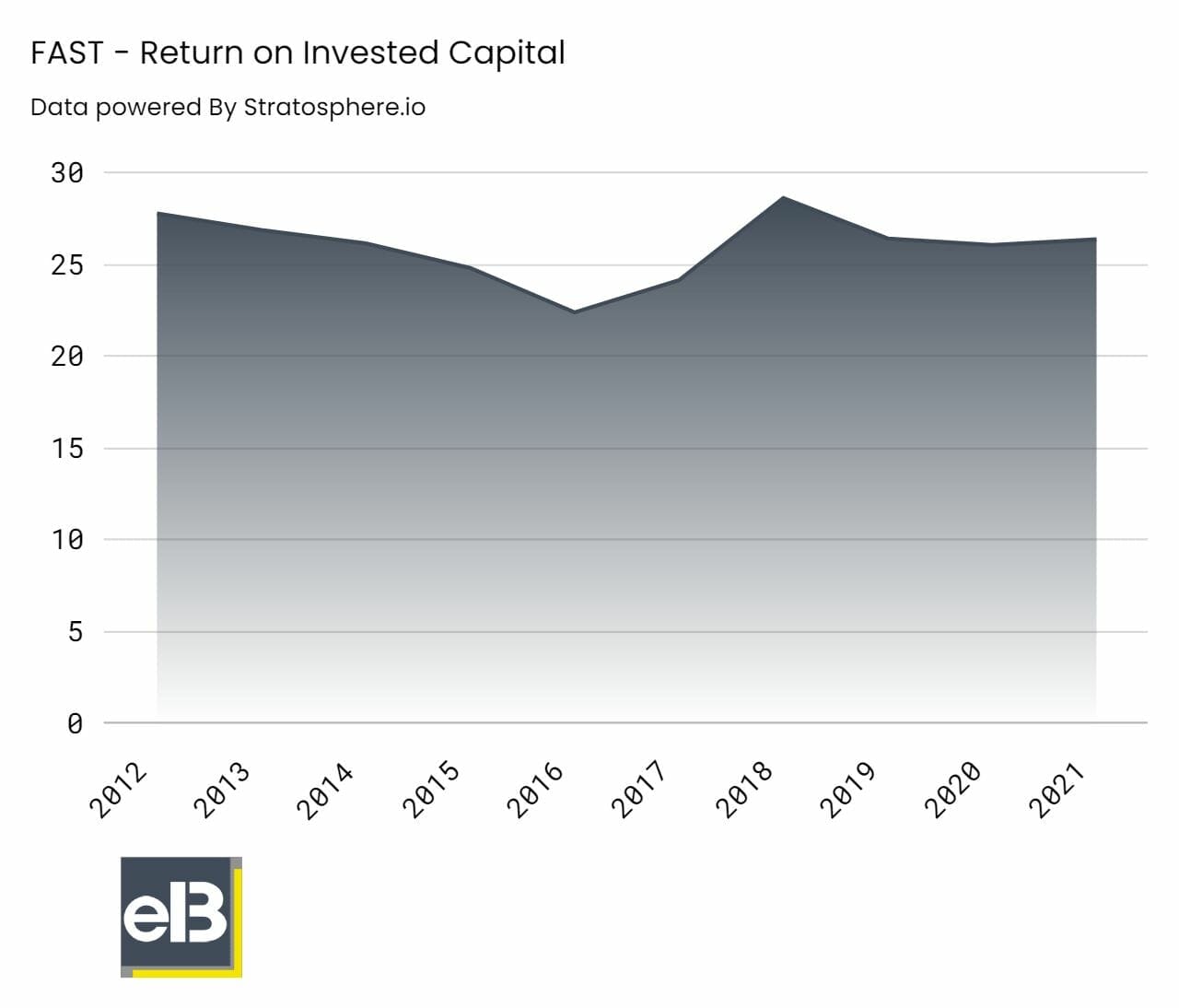

- Returns on Invested Capital > 20%

- Revenue growth > 10%

- Earnings growth

- Dividend growth

- Debt to equity < 2

- Valuation metrics such as P/E, P/FCF, and DCF

These qualities make businesses ideal for long-term purchases and hold investing. A prolonged holding time enables the high ROIC to compound, increasing the value of the enterprise (like rolling a snowball in the snow).

Remember that these suggestions remain subjective and must change depending on the industry or sector you analyze. For example, looking for a bank to generate consistent 10% revenue growth doesn’t seem fair.

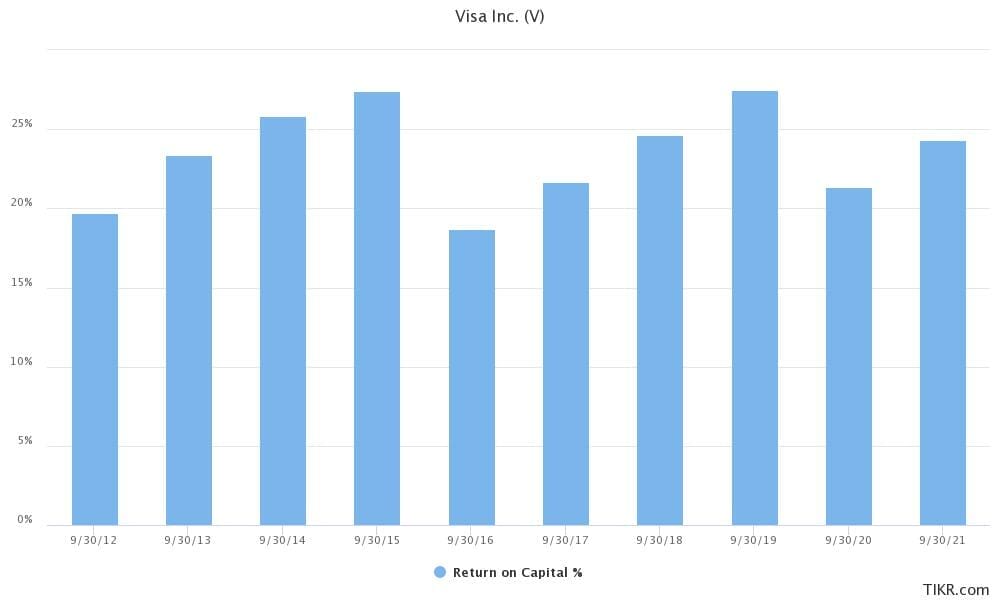

If we look at Visa’s return on invested capital, we can see a strong correlation to the stock returns compared to the ROIC.

Impressive, 18.1% CAGR return over ten years, while the ROIC hovered around 20% or higher during the same period.

I chose return on invested capital (ROIC) for a reason. Studies have shown this one metric helps investors choose quality companies far better than any other.

“Leaving the question of price aside, the best business to own is one that over an extended period can employ large amounts of incremental capital at very high rates of return.”

–Warren Buffett, 1992 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter

Return on invested capital is the component that sets a quality company apart from the competition. ROIC is more of a three-dimensional indicator of how much money a firm makes compared to the capital invested in its operations.

By dividing an organization’s operational profit by its operating capital, ROIC is determined (physical assets plus net working capital). The return on operational capital increases as operating profit as a percentage of operating capital increases, and vice versa.

A growing ROIC is a sign that a company is doing better since the more money it can make, the more it can invest in the company annually.

Businesses with a high ROIC might make more money while spending less. They don’t have to rely on huge physical assets, which cost more money.

For instance, mining businesses depend on their physical assets, their mines, to make money. However, the costs of purchasing, digging, and maintaining the mines must be covered by operating cash flow, placing a heavy burden on the company’s financial resources.

Companies carrying higher ROICs tend to have moats.

Why is this important?

Here’s an excerpt from a recent Pat Dorsey interview that I think highlights it perfectly:

“When people are thinking about how to value a moat, and when a moat is really valuable and when it is less valuable, the key to think about is the length of the runway. What are the reinvestment opportunities that a company has? So Visa or MasterCard or a Chicago Mercantile Exchange [CME] or a C.H. Robinson [CHRW] or Expeditors [EXPD], these are all companies that are in growing markets or in mature markets with very small market shares. There’s a lot of opportunity to reinvest capital at a high incremental rate of return. That moat and that ability to reinvest for ten years before someone really wanted to steal your competitive lunch are incredibly valuable.

Contrast that with a Microsoft [MSFT] or a McCormick [MKC], both of which have very strong moats, but the volume of Windows isn’t going up much year to year; the volume of spice consumption in the U.S. is not increasing much year to year. McCormick’s moat doesn’t really add a lot of economic value; it adds stability and predictability, but it’s not worth paying a ton of money for because it doesn’t allow the company to grow all that much.

Whereas the moat for a business that has reinvestment opportunities is very, very valuable. That’s often how I think about the “when do I want to pay up for a moat” question, is whether that moat is actually going to allow the company to reinvest a lot of capital at a high rate of return, or does it just add stability and predictability.”

Example of a Quality Company Selling for a High Price

For our guinea pig, let’s look at Fastenal (FAST), the wholesale distributor of industrial and construction supplies. They sell nuts and bolts for a wide range of uses.

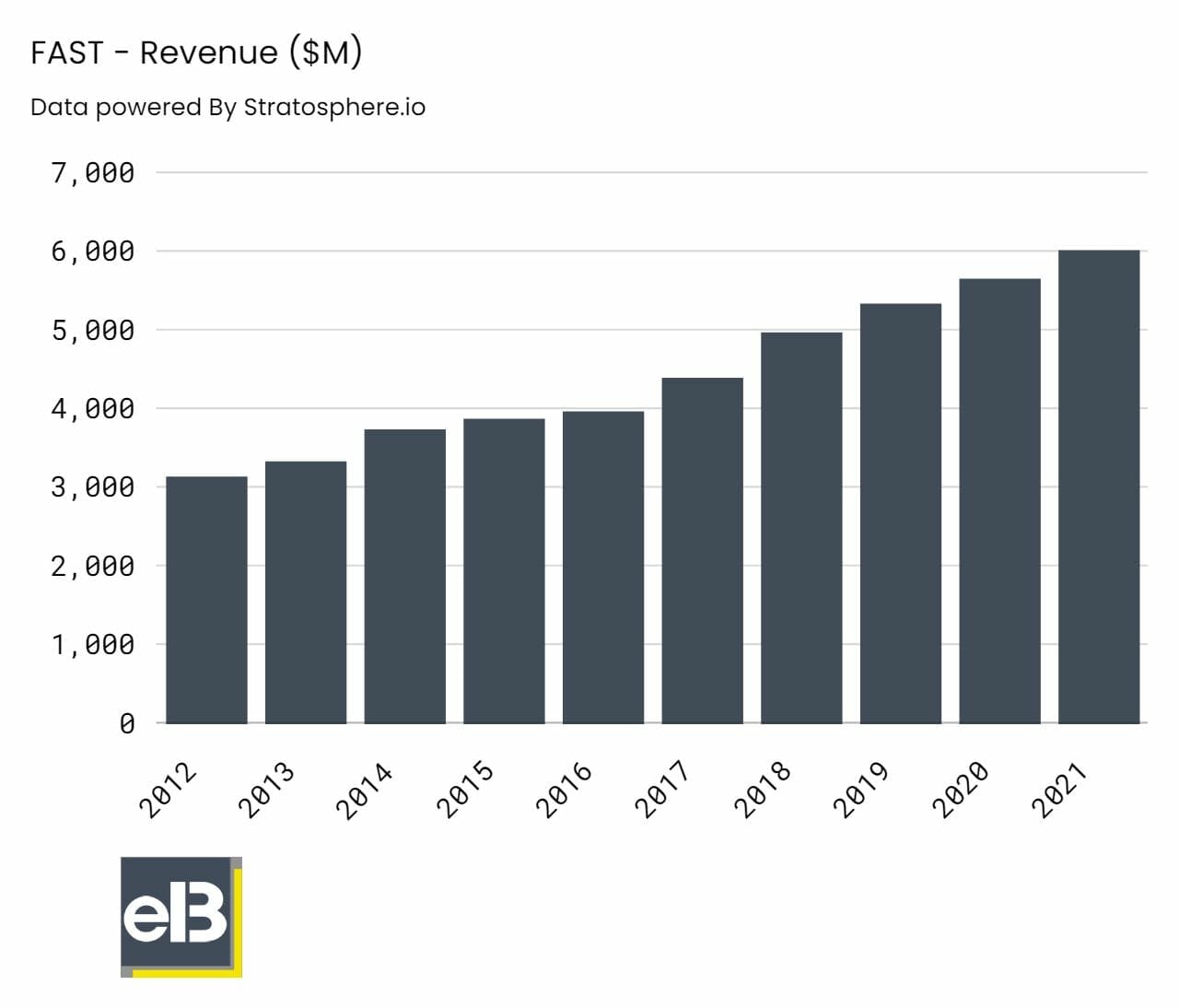

The company exhibits all the signs of a strong company with a moat. We can see from the following charts the company generates strong returns. Over the past five years, the company has compounded returns at a 15.85% CAGR, and for the last ten years at an 8% rate.

If we look first at revenues, we see:

Considering the industry, overall revenue growth of 6.74% meets our goal of growing revenues over a longer period. The company occupies a single-digit market share, with plenty of runways ahead.

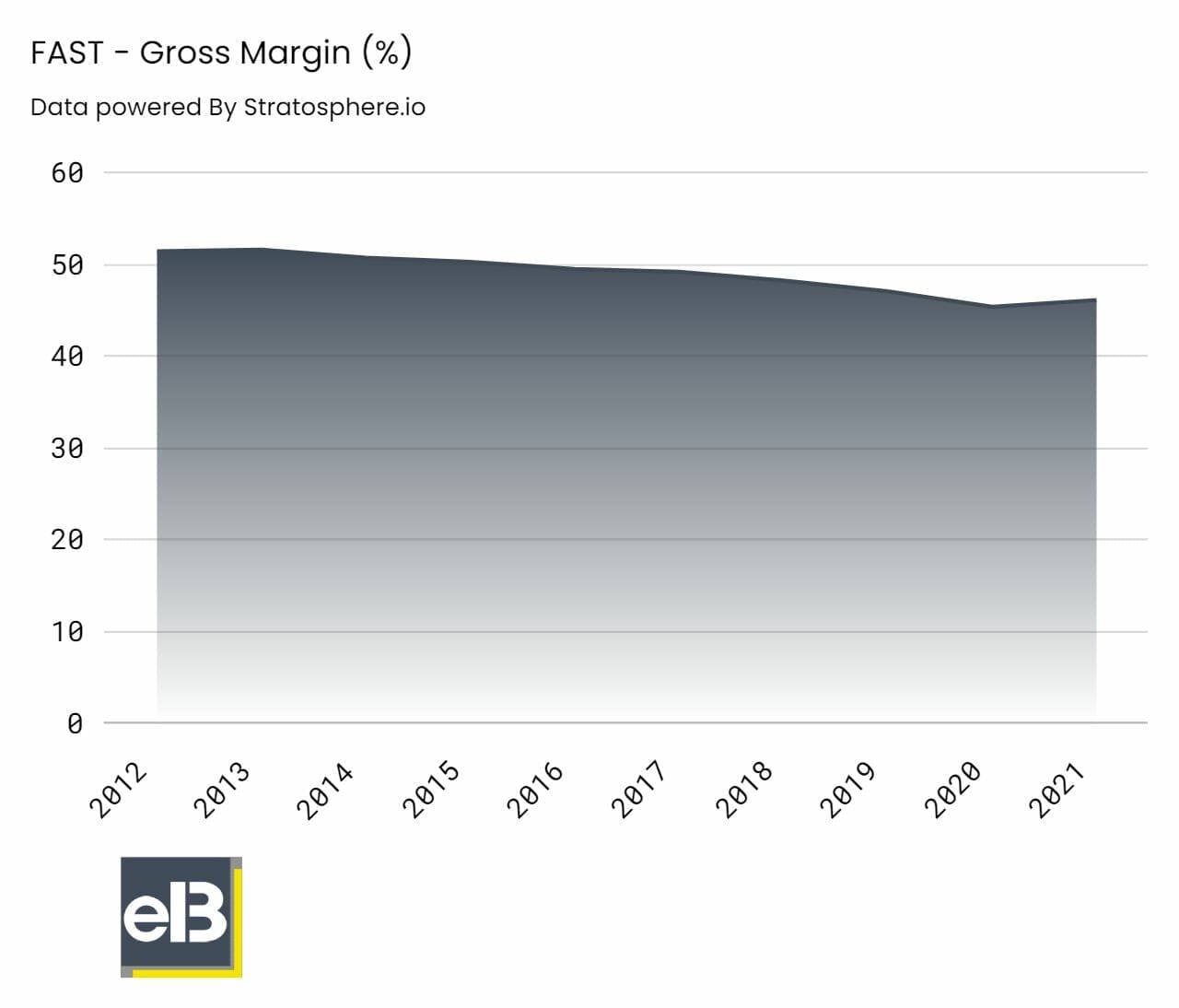

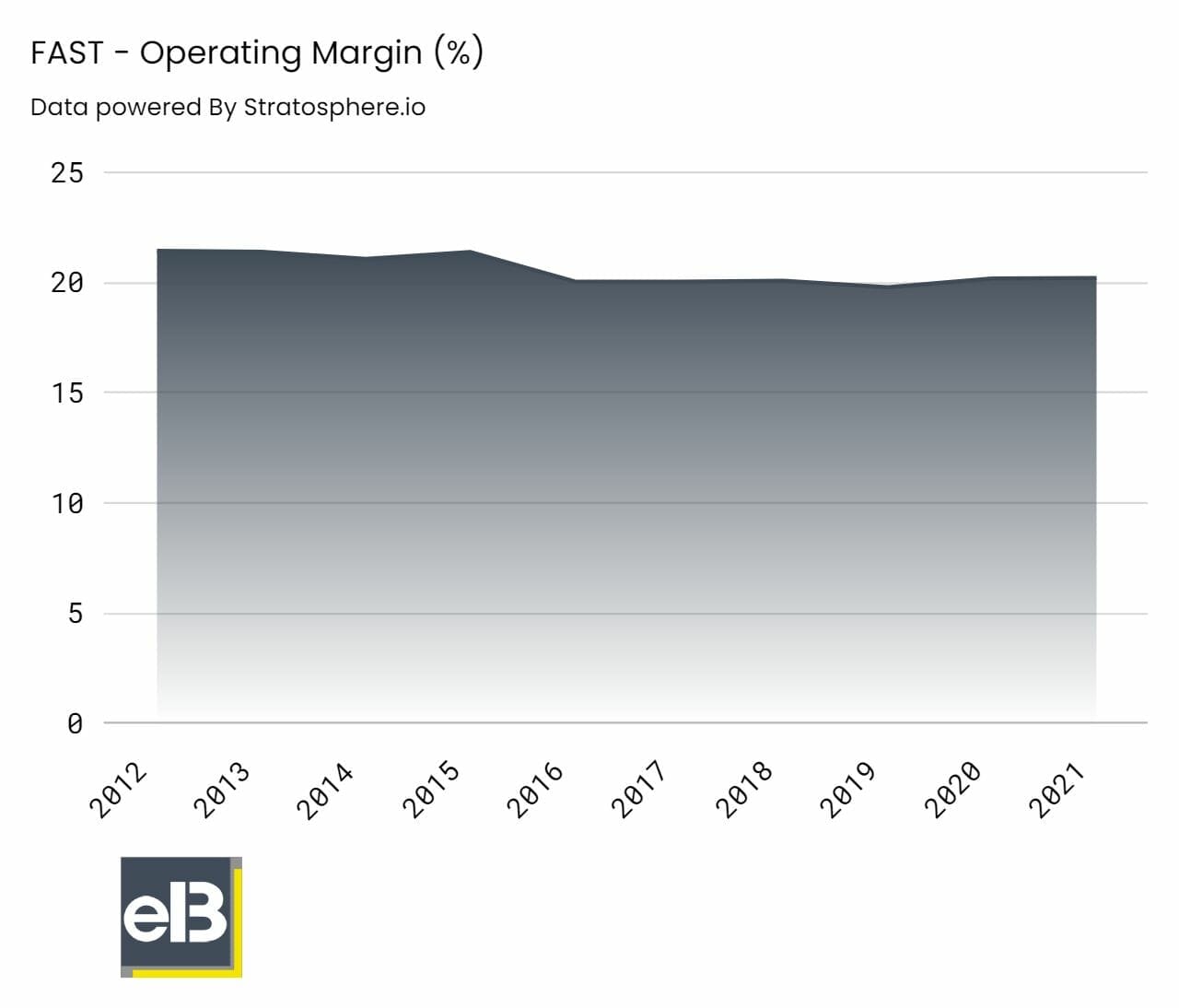

Next, we can see the company generates plenty of profits from its revenues, the costs of goods, and operational costs.

Both gross margins and operating margins continue growing in lockstep with revenue growth. This indicates Fastenal contains operating and cost leverage, meaning as they grow revenues, they improve profitability, which indicates a strong business with great management.

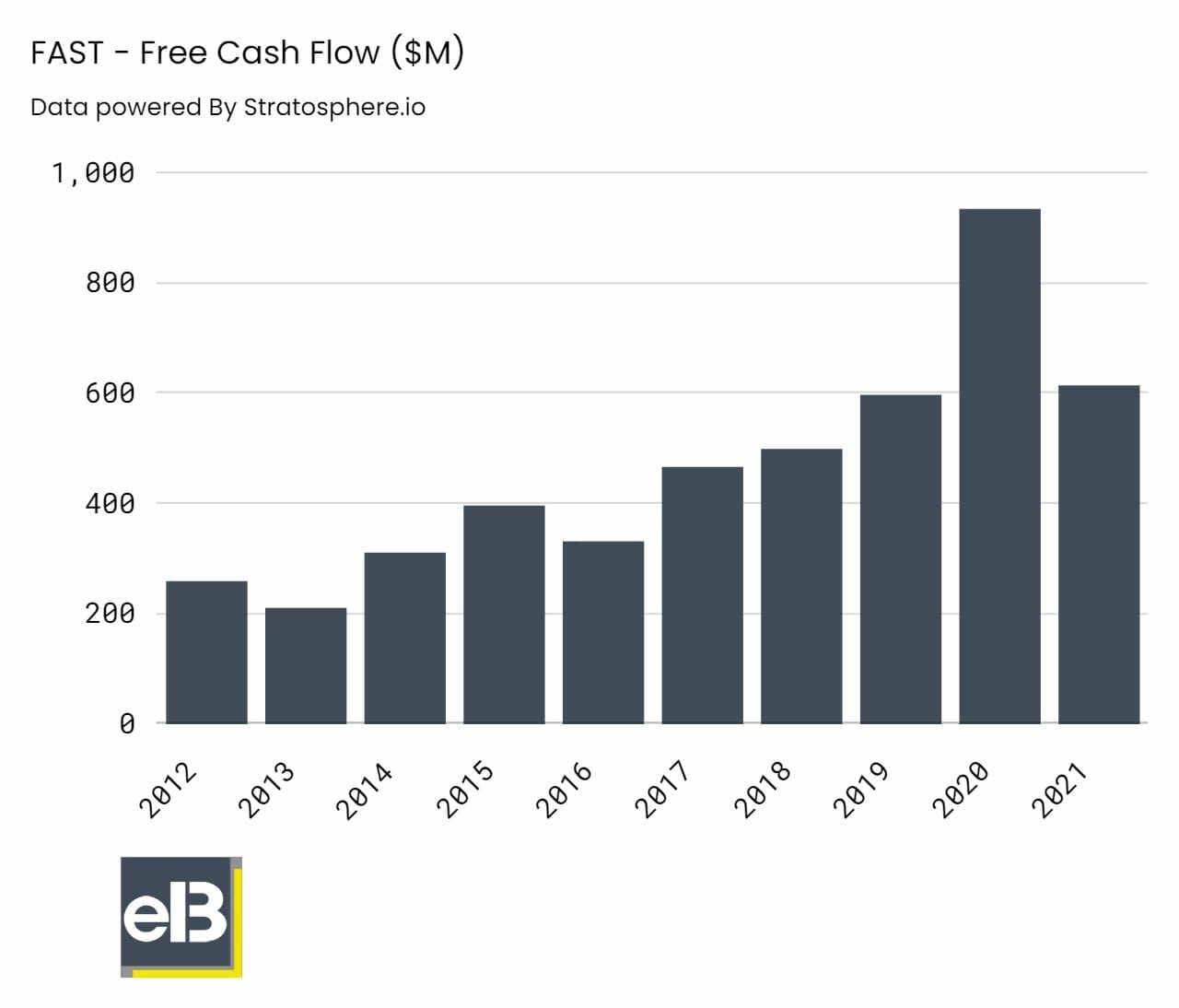

As the company grows revenues and margins, these flow to generate growing cash flow, the lifeblood of any great business, allowing Fastenal to reinvest to continue growing.

The free cash flow growth leads us to the return on invested capital. Fastenal has generated great returns on invested capital over the past five years, with over 33% average returns. These investments and efficiency in investments allow Fastenal to continue reinvesting in the company without diluting or taking on additional debt.

Those returns on capital far exceed Fastenal’s cost of capital or WACC. The greater the gap between ROIC and the cost of capital, the more efficient the company is and more profitable over the long run.

Looking at Fastenal’s balance sheet, the company carries only $764 million in debt. The debt levels hover around the free cash flow generation, indicating a strong balance sheet—the debt to equity ratio functions around 0.2, well below the levels we like to see.

Finally, we arrive at the valuation of the company. We can see from a relative basis, Fastenal trades at elevated levels.

P/E ratios ranged from 37 to 24 over the past five years, and P/FCF (price to free cash flow) levels were 50 to 27 over the same period. All of those remain elevated levels and indicate the market continuing to pay higher prices for Fastenal earnings and free cash flows.

Running Fastenal through a DCF valuation, we get a fair value of $30, compared to the current market price of $47.

All of this tells us Fastenal sells for an elevated price compared to the “fair” value of the company.

Our objective is to determine whether those predictions are accurate and determine what kind of runway Fastenal has to continue growing and taking market share.

This is where the hard work starts; before buying a fantastic company like Fastenal, we need to determine whether it is “worth it” to pay up for the company or move on.

Buying a great company like Fastenal takes diligence and insights into the industry. We must move beyond the numbers and determine whether the company’s great ROICs will continue and if it can continue to grow into its long runway.

If indeed they can, then an investment in Fastenal might make sense, but we must make those determinations first. Buying strictly because it has great ROICs and other metrics will lead to many heartaches.

These insights and ability to “see” into the future are some of the many traits setting investors like Buffett, Munger, and others apart from us mere mortals.

Investor Takeaway

Buffett outlines his investment style using four filters to find great companies. Those filters are:

- Businesses he understands

- Favorable long-term financials

- Able and trustworthy management

- Fair price tag

These simple but not easy filters can help us find great investments. And as Buffett and Munger have both espoused, sometimes paying a fair price for a great company far exceeds waiting for those companies to come to you.

Because, frankly, they may never fall to a price we like.

I am not advocating you go out and buy any company at any price. Instead, we need to do our due diligence and investigate the company and its long-term prospects before we consider paying a fair price for a Costco, for example.

We cannot buy because a group of metrics or ratios tell us a company offers us a great opportunity. The price has to offer a fair deal for us too.

And with that, we will wrap up our discussion today.

Thank you for reading today’s post; I hope you find something of value. If I can be of any further assistance, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Until next time, take care and be safe out there,

Dave

Related posts:

- Stock Buying Checklist: Essential Part of Evaluating Stocks (Example Checklist) The stock buying checklist is one of the essential tools to any investor, in my opinion, and to most, an underutilized tool. Using a checklist...

- Does Tesla Pay Dividends? Updated – 10/16/23 One question that I think is imperative that any investor knows the answer to is whether or not the company that they’re...

- Stock Pickers: 8 Vital Questions to Answer for Your Bottom Up Investing Approach A bottom up investing approach is different from a top down strategy because it focuses on a business rather than the greater economic picture. Where...

- What the Berkshire Hathaway Owner’s Manual Says About Buffett’s Approach Ever wonder what blueprint Warren Buffett uses? Or how he manages his company or decides what companies to invest in or buy outright? Well, we...