With hindsight, the Circuit City bankruptcy looked like a similar story to Blockbuster’s. It was innovation, new concepts and businesses, defeating the old.

However, there were clear red flags before this sudden collapse. We can see them by looking deeper at the accounting and financial statements of Circuit City.

Circuit City collapsed very, very quickly.

Within two years, the company went from (1) increasing comparable sales (same-store sales) to (2) decreasing them, to (3) bankruptcy.

Before this, Circuit City’s stock outperformed the S&P 500 from 2003 to 2007. From its fiscal year 2007 high of $31.54, it then crashed to $3.47 in fiscal 2008. It finally went to bankruptcy within 8 months of the filing of their 2008 annual report.

Amazing, management seemed to be in denial throughout the whole process, approving board compensation in the months before the bankruptcy. The CEO did step down, but it was too little too late.

To really understand how Circuit City was sitting on a house of cards, we need more than a surface level education on accounting.

Let’s tackle all aspects of the Circuit City bankruptcy, by breaking this post down into these sections:

- Simple Red Flag: Negative Earnings

- How Circuit City Actually Seemed Healthy

- The Deep Dive into Circuit City’s Financials

- Investor Takeaway- Hubris Before the Fall

Let’s start on the easiest way that I know to avoid many bankruptcies before they happen; it starts with a simple, surface level, yet powerful indicator.

Simple Red Flag: Negative Earnings

As the great investor Warren Buffett says,

“Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

–Warren Buffett

In the case of Circuit City, the company’s house of cards seemed to come out of nowhere to most. In reality, it was because their house was built on sand.

There was little margin for error. This is usually fine in business, until you approach the inevitable economic slowdown. That’s when the weakest businesses fail to survive.

How Circuit City Actually Seemed Healthy

We’ll start by looking at Circuit City’s business strategy. Despite a weak balance sheet and fierce competition, the company was dedicated to expanding their concepts.

A few statistics pulled from their last annual report (10-K) before bankruptcy:

- Superstore openings (domestic)

- 2008: 43

- 2007: 23

- 2006: 18

- 2005: 31

- 2004: 8

- 2003: 8

- 2002: 11

- 2001: 24

Not only was the company growing, but they were growing aggressively.

There’s nothing wrong with that per se, but it should be done while still leaving a safe margin of safety rather than pursuing growth at all costs.

By most shortcut metrics used by investors, Circuit City looked healthy.

In fact, the company’s debt was inconsequential. Using a standard risk metric like the Long Term Debt to Equity, Circuit City was healthy on all accounts in 2008:

- Long Term debt = $57,050 thousand

- Shareholder’s equity = $1,503,175 thousand

- LT Debt to Equity = (57,050) / (1,503,175)

- LT Debt to Equity = 0.04

Anything below 1 for LT Debt to Equity is considered sufficient, so the company appeared very safe here. In fact, if you include the company’s cash and cash equivalents, they were actually net debt free.

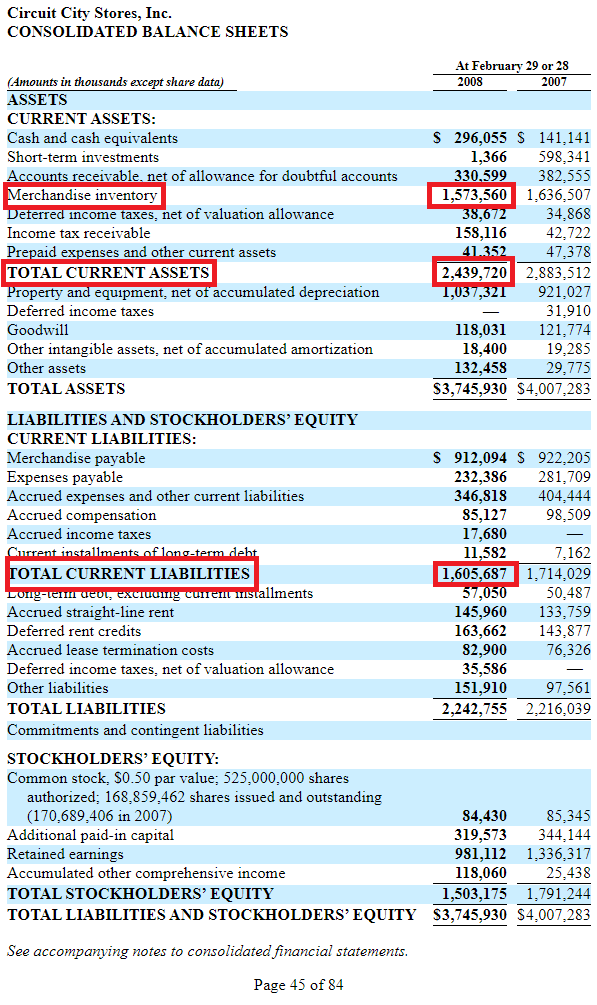

Another simple balance sheet-based risk metric is the current ratio.

This takes current assets minus current liabilities, which is supposed to give investors a picture of the company’s liquidity, because it roughly measures a company’s short term expenses versus what should be readily liquid assets.

Roughly is a key word in that, however, but their current ratio, where anything above 1.0x is good, was pretty healthy:

- Current assets = $2,439,720 thousand

- Current liabilities = $1,605,687 thousand

- Current ratio = (2,439,720) / (1,605,687)

- Current ratio = 1.52x

Finally, a third risk-based ratio on a company’s leverage called the coverage ratio looks at a company’s income statement (P&L) and determines their ability to pay on the interest of their debt.

The formula for this is:

= Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense

Maybe it was this formula that gave the earliest indication of potential troubles ahead.

But, many investors will make exceptions for unsatisfactory metrics. This was no exception, especially for the years of 2007 and 2008. During these years, the economy was really starting to slow down. It’s easy to see how some investors would look at the company’s regular profitability to determine their long term solvency.

In this case, looking at 2006, Circuit City was able to earn an EBIT (or Operating Income) of $214,762 thousand. Compared to interest expense of $3,143 thousand, you get an Interest Coverage Ratio of 68x, which would be outstanding in all respects.

As we continue to investigate this company’s financials, we’ll find that they looked relatively healthy even with a deeper examination.

But we’ll find there’s one tiny detail which outlined for all just how precarious the company’s situation really was.

The Deep Dive into Circuit City’s Financials

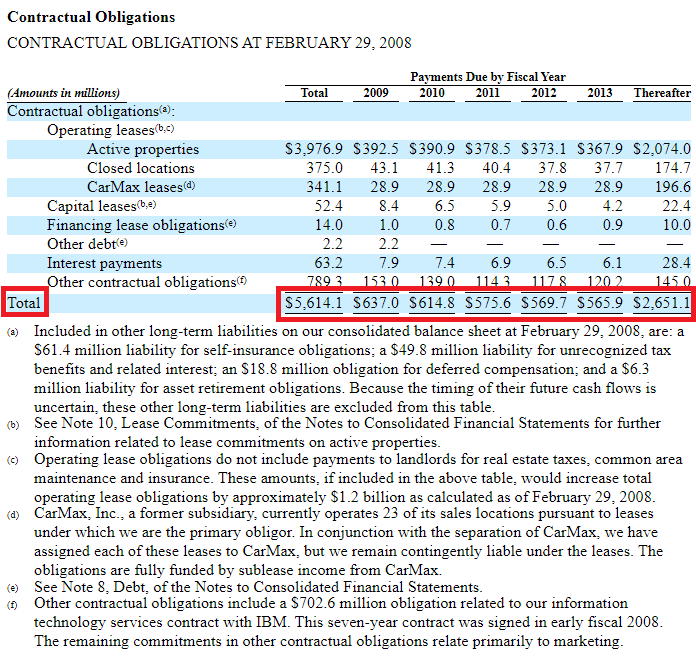

A great section for determining (solvency) risk from a company’s annual report is under Contractual Obligations.

For Circuit City, everything appeared fine and dandy:

Note that these numbers are in millions while the others in the financial statements are in thousands.

Even still, though the company has $392.5 million in Operating Lease expense coming due next year, this is an expense. It does not come out of earnings or cash flows but rather is a regular expense for operating the business.

It’s an expense which comes out of revenues, of which the company regularly records numbers in the $11 billion range.

More specifically, the company outlines these expenses as part of operating expense, after which you are left with Operating Income.

While this section usually uncovers many situations of impending doom for companies, Circuit City was just fine here, again, because it had very little debt on its books and not much coming due soon.

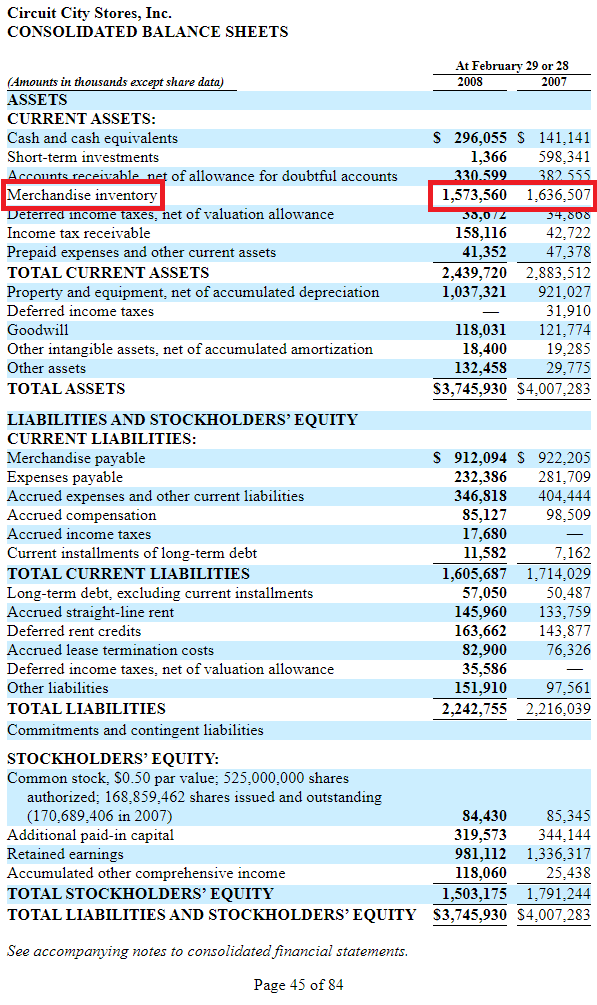

Speaking of its books, let’s go back to Circuit City’s balance sheet again but with a fine-toothed comb this time.

Here’s a screenshot of their entire Balance Sheet, with a few highlights:

I want you to observe the line item Merchandise Inventory, which reveals the big problem for the company.

Merchandise Inventory is very much an asset, because when it is sold, it creates revenues and profits for a business.

Big box retailers such as Circuit City will routinely carry large inventories. This is because, in general, the more inventory around, the higher potential sales you can make.

As retailers anticipate big rushes in sales, they will stock up on their inventory. There’s few things worse in this business than drumming up a bunch of customer demand only to be completely out of inventory. Nobody goes home happy there.

However, inventory is a double edged sword because when it sits, it’s a drag on the business.

The longer that inventory sits on shelves, in general, the less valuable it becomes. Eventually businesses will want to get it off their hands, and so they’ll mark down, or reduce the price, of items. This is done to clear way for some (hopefully) better selling merchandise and at least recover some sort of revenues from those investments.

Where a business can get into trouble is when demand suddenly dries up, and there’s too much inventory sitting around not making sales.

If a business doesn’t have the demand for its inventory, it can’t make sales. Even though at the same time, it still has to pay operating expenses such as employee wages and rent expense.

What should be a liquid asset such as inventory actually does nothing for the business. It’s during times of adversity where businesses without a safety buffer (like Circuit City) can come across serious problems.

Let’s highlight that liquidity situation again, but just focus on current assets and current liabilities.

If we were to take a worst case scenario, which is one where customer demand dries up in a serious way and inventory has to sit, can the company survive long enough for demand to recover?

Assume that zero inventory is sold—can the company still pay its short term liabilities?

In the case of Circuit City, that answer was a resounding NO. If you subtract Merchandise inventory from the company’s current assets, you get an estimate for the assets which are actually liquid during a crisis.

Comparing these to the company’s short term expenses (current liabilities), we’ll see that their liquid assets are NOT enough to cover even 1 year’s worth. That’s how the 2009 slowdown was able to be so catastrophic.

By subtracting inventory from current assets and comparing to current liabilities, we get this number:

= Current assets – inventory = (2,439,720) – (1,573,560)

= Current assets – inventory = 866,160

= Current Liabilities = 1,605,687

= (866,160) / (1,605,687) = 0.54

The fact that this ratio is below 1 tells us a few things. Maybe the biggest is that in worst case scenarios, the company is not likely to pay its short term expenses without help. It would have to sell long term assets or obtain financing (through debt or equity).

This is actually a ratio that’s called the Quick Ratio, and it’s the perfect answer to Circuit City’s demise.

Because here’s what happens during a financial crisis…

Not only do customers tighten their belt, but so do banks and investors. It’s much harder to get banks and investors to lend you money during a crisis. This is true even if your balance sheet is strong; if it’s not liquid, it doesn’t do you much good.

For Circuit City, with $1.5 billion in Inventory and $1.0 billion in Property and equipment (a Long Term asset), there’s a significant portion of their assets which are not very liquid. This isn’t a problem until the markets and economy tighten up (they always inevitably do).

That’s why the Debt to Equity ratio and Current Ratio did not help in this case. Those formulas naturally do not account for assets that can be illiquid (not quickly converted to cash).

You’ll see some companies keep Marketable Securities as Long Term Assets on their Balance Sheets, because at least in cases of crisis they can usually sell some of these off to at least get some infusion of cash.

Circuit City did not have access to assets such as these. Once they started posting heavy losses, they found themselves on a very quick and slippery slope to bankruptcy.

Investor Takeaway- Hubris Before the Fall

I mentioned at the top that management had hubris before the fall, and it’s clear after we really dig-in.

It was hubris that caused management to continue to overextend and overleverage itself. They aggressively opened stores and bought back shares without keeping short term liquidity in mind.

It was hubris that caused the company to adapt to declining conditions way too late. Even $117 million in losses through the first 6 months of 2007 could not convince the company to stop its repurchases. They bought an additional almost $200 million in shares as things were starting to head south.

I don’t want to imply that as investors, we can presciently identify and avoid every single bankruptcy before it happens.

But sometimes it is better to be safe than sorry.

And just because you have many businesses around you with Quick Ratios below 1, doesn’t mean that you, as the investor, have to invest in them.

As fast as recessions and stock market crashes hit, so can bankruptcies.

It’s up to you to really dive into these details, and keep the worst case scenario in mind.

As Warren Buffett’s chief partner Charlie Munger says,

“All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.”

–Charlie Munger

If the story of the Circuit City bankruptcy can tell us anything, it’s that real liquidity matters, and can be the difference between failure and survival during the toughest times.

Related posts:

- The Best Way to Invest in Insurance Companies: How to Analyze Their Stocks Insurance, one of the necessary evils of today’s world, right? We all have to have it in case of that one day you will need...

- 2009 Bankruptcies Feature: Monaco Coach Falls to a Black Swan Event Newsflash—even profitable companies can suddenly go bankrupt. Unlike many of the 2009 bankruptcies, Monaco did not have much debt on its balance sheet. It was...

- A Dive into Walmart’s Supply Chain and Understanding Vendor Management Inventory Having a strong supply chain is important for any retail outlet, but the retail giant, Walmart, has mastered the game and hasn’t turned back. When...

- Homebuilding Industry Breakdown: Revenue Drivers, Business Model The homebuilding industry is easy to understand as a concept. Companies build new homes, and customers buy and live in them. But there are several...