A bond indenture is simple in theory. It’s a document outlining the terms of a bond; what the issuer’s (or borrower’s) obligations are to the bondholder (lender).

A common application of a bond indenture today is with publicly traded corporations who issue bonds to investors through investment banks like JP Morgan or Bank of America. This document will precisely outline things like the amount owed, both principal and interest, and at what cadence (or times due).

Examining the bond indenture document itself (rather than reading a summary) is important because it could contain certain covenants, which potentially restrict future actions of the issuer and could impact a company’s financial performance for equity investors.

Unfortunately bond indenture documents tend to be filled with legalese, making them hard to translate even for the most willing CFA graduate or candidate. We’re going to tackle this today with the following sections:

- Why are Bond Covenants there in the first place?

- How to Find a Bond Indenture from a Company’s 10-k

- Should I read all of a company’s Bond Indentures?

- Other Indentures to Be Cognizant Of

- When Bond Indentures Are Violated

Hopefully this post will make that task easier by providing context through a real-life example and its publicly filed bond indenture documents. But first, let’s start by talking about covenants.

Why are Bond Covenants there in the first place?

Covenants can be an important part of a bond indenture especially if the issuer has more of a default risk, because as you might learn in Corporate Finance 101, the financial incentives of bondholders and equity holders don’t always align.

For example, equity holders might like to see a company lever up a very conservative balance sheet in order to spurn additional growth opportunities in the future for free cash flows and earnings.

But since bondholders are generally paid only on fixed principal and interest payments and receive no benefit from the growth of a business (other than potentially reduced default risk), an aggressive levering of a business might benefit equity holders (or owners) of a business while potentially endangering bond holders to greater risk.

To protect against this potential of a conflict of interest, bondholders might demand covenants to reduce the ability of the company to lever in the future, either by requiring the company to adhere to minimum levels of solvency as measured by certain metrics, or requiring prepayment before accruing additional debt.

Keep in mind that bond issuances and pricings are a negotiation just like the buying and selling of bonds or stocks is.

A more credit-worthy issuer might get away with a bond indenture with no debt covenants because of its strong financials and track record, or an issuer might pay a higher yield in lieu of more restrictive debt covenants, or vice versa, just as an example.

How to Find a Bond Indenture from a 10-k

Now let’s get to the meat and potatoes through a real-life example of a bond indenture. I’m going to take a publicly traded company called Casey’s General Stores ($CASY), a company who disclosed their bond covenants as a risk factor in their 10-k.

I’ll use the company’s latest 10-k from a great website called bamsec.com.

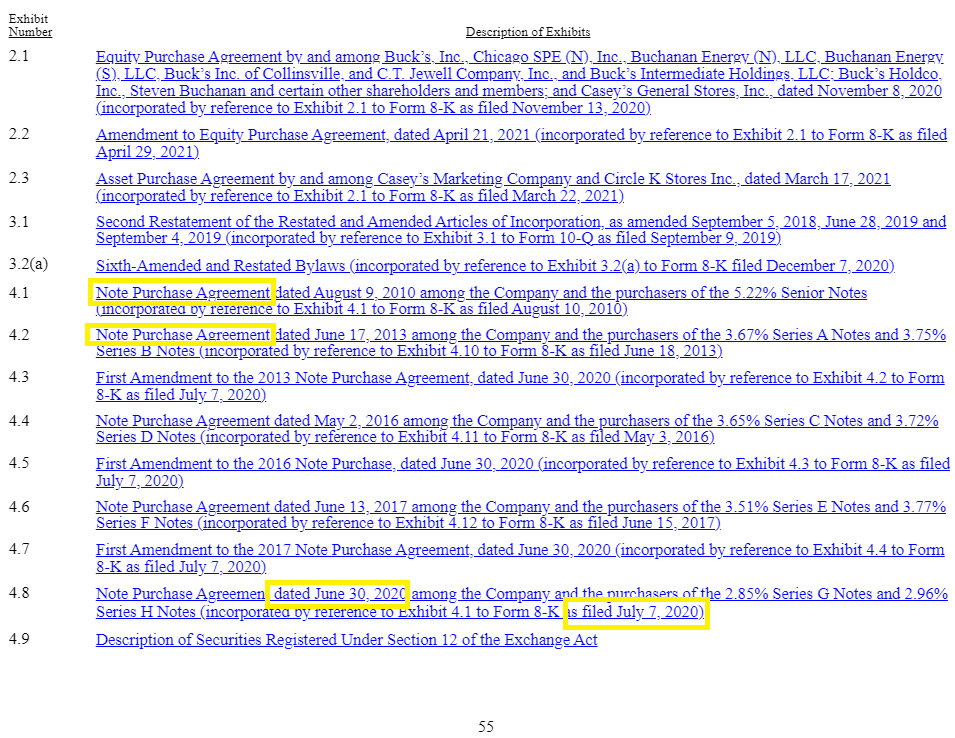

Usually you’ll find bond indentures and other related documents in the “Exhibits” of a 10-k, which are usually found at the bottom of the document. If you’re having trouble locating a particular bond indenture, you might want to look at the Debt section of a company’s Notes to the Financial Statements and see which exhibit the company references to explain their debt terms (it might direct you to an 8-k, for example).

For Casey’s, we can see various “Note Purchase Agreements”; since bonds are often referred to as Senior Notes we can think to start here.

I’m going to click on the latest one first, dated June 30, 2020 and filed July 7, 2020.

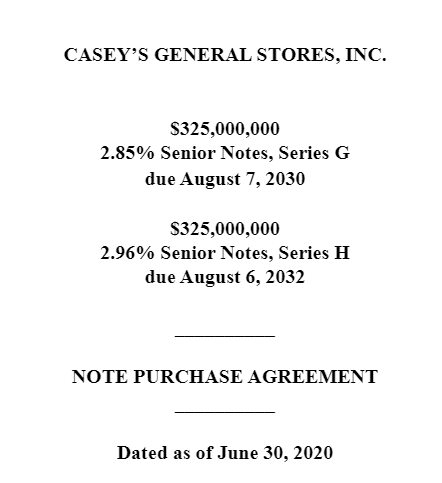

Right at the top, we see the following terms:

If you scroll through the table of contents, you’ll see sections such as 8. MATURITY OF THE NOTES; PREPAYMENT, which will tell you whether the $325,000,000 principal and interest is due in installments or all at once at the due date (known as a balloon payment).

What I’m interested in, and any stock market investor should be, is any restrictive debt covenants. In this case, we can see the following sections which look interesting:

- 9. AFFIRMATIVE COVENANTS

- 9.10 Excess Leverage Fee

- 10. NEGATIVE COVENANTS

- 10.1 Financial Covenants

- 10.2 Priority Debt

- 10.5 Merger, Consolidation, Etc.

You could certainly read every section and use an extensive knowledge of legalese to do so; I’m not a lawyer and so I have to make best estimates instead (as I think most investors should do with all parts of fundamental analysis).

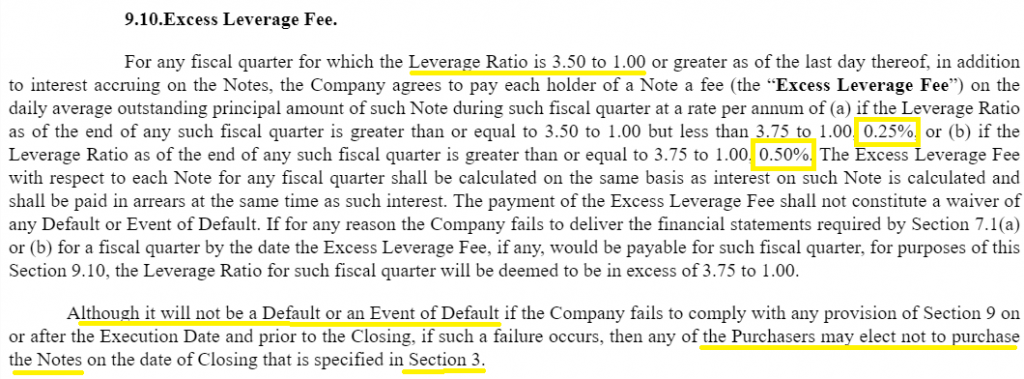

Here’s what this indenture document describes under Excess Leverage Fee (with all highlights mine):

Here we can see pretty clearly that there’s a sort of maximum Leverage Ratio that would behoof the company to stay under. I highlighted at the bottom how it does not indicate default, but it does limit some of the other conditions, which could be further investigated in Section 3.

In this case, we need to understand that “Leverage Ratio” can be defined differently depending on who you’re talking to, so we need to find how Leverage Ratio is defined in this bond indenture.

We could certainly search (“ctrl+f”) the document to find where Leverage Ratio is defined; I’m skipping to section 10 because I know we’ll see the definition there.

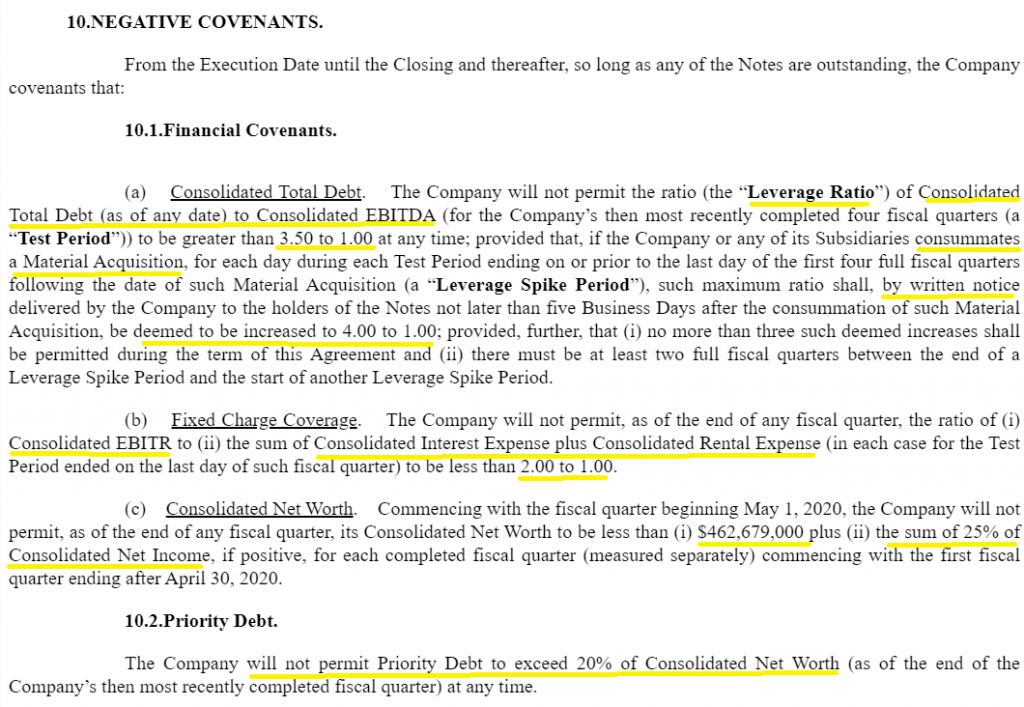

Here’s section 10.1 Financial Covenants, also clear for the most part (highlights mine). Section 10.2 Priority Debt is a small section, so I included it as well.

Admittedly this section is a little bit more intense, but if we read it closely we should be able to intelligently follow along.

1— First we get the definition that Leverage Ratio is defined as Consolidated Total Debt / Consolidated EBITDA of the last 4 quarters. Like stated in 9.10, this should not increase above 3.5.

But, we see an exception where if the company makes a “Material Acquisition”, it is allowed to be increased to 4x for 4 quarters with enough written notice to the bondholders. This is where we see why 9.10 is there, where the company could go above a Leverage Ratio of 3.5 temporarily after an acquisition but would have to pay the Excess Leverage Fee.

2— The Fixed Charge Coverage is the second covenant to be aware of for this company. We can see the formula is defined as (all values are “consolidated):

= EBITR / (Interest + Rent Expense)

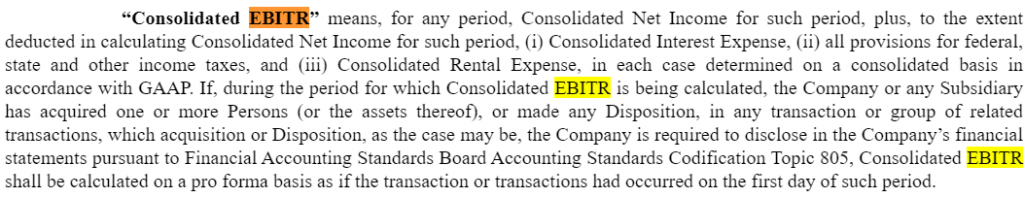

Personally, I’m not really familiar with “EBITR” so let’s dig further. By inputting “EBITR” into a search function, we find it additionally mentioned here (in Schedule B; DEFINED TERMS):

Basically we have Net Income + Taxes + Interest Expense + Rental Expense.

So the EBITR translates to Earnings Before Interest and Taxes and Rental Expense. Makes sense after finding the definition but always good to double check if you’re unsure.

This Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio should not be below 2x. Simple too.

3— Consolidated Net Worth is also defined in Schedule B; it’s simply consolidated Shareholder’s Equity which is what I would’ve guessed.

We have a very specific number that Shareholder’s Equity must stay above, presumably to attain a desired Debt to Equity type ratio you’ll tend to see in balance sheet analysis.

But, this covenant also allows for 25% of Net Income to be added to Shareholder’s Equity in case that equity dips below $462,679,000.

Should I read all of a company’s Bond Indentures?

I would say that the answer to this question should be a yes, but with a stipulation. I think doing this could be very tiring for an investor and all such time consuming efforts should be weighed against finding new and better opportunities or doing different kinds of detailed research on the same company.

Here’s how I approach which some of you might find useful.

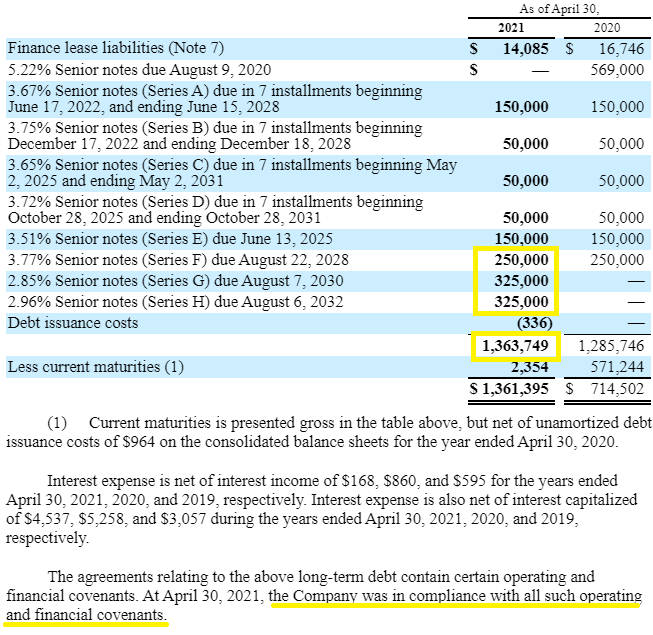

You’ll want to go back to the company’s Notes to the Financials in order to see exactly how many senior notes or other bonds the company has issued up to now.

Here’s what that looks like for Casey’s:

In this case they have quite a number of other notes we could look at, specifically Series A-F since we looked at G and H already.

Just by looking at Series F we could cover over half of the principal value of their notes outstanding, which will paint a pretty good picture for us.

Of course, the fact that the company stated that they were in compliance with all of their covenants (bottom of the screenshot) is something you’ll want to see particularly if these covenants were mentioned at all in the 10-k (such as being a “Risk Factor”).

Another Way to Evaluate Bonds (Shortcut)

Luckily for investors, there are people who analyze bonds and long indenture documents such as these for a living—one of the most prominent firms being Moody’s.

Moody’s actually reports these for free who enters their email and makes a free account with them. You can search a wide range of securities that the company covers, and they cover a vast portion of the S&P 500.

However, Moody’s might not cover the bonds of companies which they find to be too speculative or risky, or might not cover a company’s bonds due to their smaller size. At least that’s what I’ve observed as I’ve used their service to look up various stocks.

Though this kind of a shortcut can give valuable, almost instantaneous insight on a company’s bonds, they should not be used as a substitute for in-depth research into a company’s indenture documents, particularly if their covenants are a known and disclosed risk factor.

If you’re looking for help in translating the ratings profile of Moody’s and one of their peers S&P, Dave did a whole guide on the topic in a great post which you can read here:

Other Indentures to Be Cognizant Of

Keep in mind that a company will also generally have indenture documents for other forms of debt, such as credit agreements which can include revolving credit facilities (similar to a personal line of credit), term loan facilities, and other similar vehicles. An indenture document associated with a bank line of credit is also another example.

These should also be linked to in a company’s annual report, and you should look for terminology which refers to these in the exhibits as well as any amendments to any of the indenture documents, which could possibly change certain terms.

I know that this can all seem like a lot, and it’s hard to imagine an investor who can get through every single document with every single possible condition and violation.

That’s why diversification is key.

You can’t control every single unforeseen event, and that includes violations of indentures just like everything else in the stock market.

In that same light, work smart and not hard.

Don’t read every word in every document just so that you can say that you can, but make sure you read enough to get a sufficient grasp on a company’s major liabilities and covenants. Being ahead of the curve in this regard can be a great advantage, particularly when things get tough.

When Bond Indentures Are Violated

Final note (no pun intended): Remember again that even bond indentures and documents are sometimes negotiable just like the prices of bonds and stocks are. Meaning, just because a company doesn’t fulfill all of its obligations or covenants doesn’t mean bondholders will immediately take action.

You only have to see how bankruptcy proceedings play out to see how debt can be restructured and renegotiated, which of course includes all of the terms in an indenture. Bondholders may choose to do this if they figure that collecting some of their principal back is better than collecting nothing.

But, if you are a long term stock market investor, I would not want to be invested in companies who are close to breaking their obligations and covenants or even doing so already.

That’s a big layer of uncertainty as an investor, and you can’t rely on this kind of a “kindness of strangers” and expect to find consistent, sustained success over many market periods.

Hopefully this blog post has provided you with an added layer of due diligence in the companies you look to invest in long term, or whatever else application you had which drew you to search for help through these arcane documents.

Related posts:

- How to Look Up Debt Covenants: A Real-life Example from a 10-k Out of the many aspects of fundamental analysis, reading debt covenants is probably among the most arduous, discouraging, and ignored part of the job. But...

- Deferred Income Tax Liabilities Explained (Real-Life Example in a 10-k) Deferred income taxes in a company’s consolidated balance sheet and cash flow statement is an easy concept in principle, but when deferred income tax liabilities...

- Types of For Sale Securities and Their Accounting Treatment (AFS/HTM/HFT) Updated 12/19/2023 Have you wondered what all those assets on an insurance company’s balance sheet were? Or why do companies carry such a large mix...

- Pros and Cons: Held to Maturity (HTM) Securities on Companies’ Balance Sheets Updated 3/30/2023 Did you know the majority of financial assets for most companies comprise marketable securities? Did you also know companies such as Microsoft, Amazon,...