Updated 3/20/2024

One thing that many investors will realize throughout their investing journey is that trading in and out of stocks can be extremely expensive due to the amount of taxes you’ll pay. To try to minimize that impact, they’ll try to tax loss harvest but if you do it incorrectly, you’re going to get crushed with a wash sale tax!

Key Takeaways:

- If you buy a stock 30 days before/after selling it, a wash sale tax occurs.

- The wash sale tax effectively resets your basis, therefore disallowing any tax-loss harvesting in that timeframe on those shares.

- Buying “substantially identical” funds will also trigger a wash sale, even if it’s a different security.

- Don’t let the tail (taxes) wag the dog (your portfolio).

In this post, I’m going to cover the following topics:

- What is the Wash Sale Tax?

- Common Scenarios Where the Wash Sale Tax Occurs

- How Does a Wash Sale Affect My Taxes?

- How Can I Avoid Paying a Wash Sale Tax?

What is the Wash Sale Tax?

When you sell a stock and then repurchase it within 30 days, a “wash sale” occurs. What this means is that the basis of your stock isn’t reset like it usually would be, but instead, it’s adjusted to reflect the original purchase and sale that you made.

Essentially, you miss out on the opportunity to use your investment loss to offset any future gains.

Let me explain with an example:

Wash Sale Tax Example

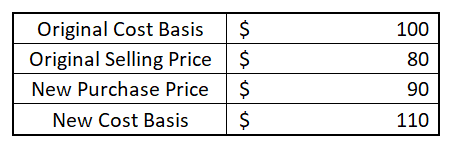

If you were to buy 100 shares of company $XYZ for $100/share, your cost basis/share would be $100. If the share price drops to $80/share and you decide to sell the shares, you will have lost $20/share.

Then, let’s say something comes out that entices you to repurchase those shares at $90/share, within 30 days from when you initially sold the shares. This then triggers a wash sale. You effectively will take the $20/share loss that you had from the initial purchase & sale and then add that to the new cost basis of your shares:

You might be wondering why all of this matters and why you should care, but as you get a little further in your investing journey and try to become a tax-efficient investor, you’ll completely understand the logic! Until then, let me show you a few scenarios to help paint the picture!

Common Scenarios Where the Wash Sale Tax Occurs

Tax-Loss Harvesting

The most common scenario I see with the wash sale tax is when people try to take advantage of tax-loss harvesting. Tax-loss harvesting is when you sell some of your investments at a loss to offset some investments that you have sold that you’ve realized gains that year.

It can be an incredibly impactful strategy when used correctly, but you must also understand the rules. With tax-loss harvesting, you’re essentially going to sell some of your stocks that have lost money within the last year and then offset those losses with some stocks that have done well for you.

You would want to do this because eventually, you will have to pay taxes on those gains if your money is in a taxable account, so you can trim your tax bill a little bit now instead of eating it all in the future. Let me explain with an example:

Example

You own two stocks, both of which you invested $10K into.

Stock A – has lost 40% in the past year – maybe because you were invested in a risky growth stock – so now you only have $6K invested. You’ve decided that you don’t think this company is a good investment anymore, and you want to get out of it.

Stock B – has grown 20% in the past year and is now worth $12K. You like this company, but you think that the valuation might be a little bit stretched.

If you sell all of Stock A, you now have $4K in losses that you would ideally offset with gains. You can sell some of Stock B to completely or partially offset those $4K in losses.

The benefit of this is that if you were to sell $2K of Stock B, you wouldn’t owe anything on those gains since $2K (gains) < $4k (losses). If you didn’t offset the gains, you’d eventually have to pay taxes on all of your gains whenever you sold the stock.

Remember, you can’t simply sell one of these stocks and then buy it back immediately—you have to wait at least 30 days before repurchasing the shares, so don’t think you’re going to pull a fast one on the IRS.

“Substantially Identical” Stocks

The other common scenario in which the wash sale tax occurs is when people think that they can buy a very similar security to avoid it, but that isn’t the case. The IRS not only looks for purchases of the same stock but also purchases of securities that are “substantially identical.”

What exactly does “substantially identical” mean? Nobody knows because there isn’t a formal definition, but we can speculate based on what we deem as substantially identical.

Example

One obvious example to me would be an S&P 500 ETF. There are tons of options out there, like VOO, SPY, IVV, and others. If you own SPY and it’s down 10%, then you can’t simply sell all of your holdings and move everything into VOO or IVV because the goal of those ETFs is the same—to mimic the returns of the S&P 500.

If you try to take advantage of tax-loss harvesting, you’ll be much better off just moving those funds into a security where you know they can’t be misconstrued as substantially identical.

How Does a Wash Sale Affect My Taxes?

A wash sale can massively affect your taxes. If you’re experiencing a wash sale tax, it’s likely either because you’re trying to tax-loss harvest or because you’re a trader and trading in and out of the same security quite frequently.

Either way, you must understand that you won’t gain any tax benefit from selling off losses if a wash sale takes place.

In the previous example, where you sell Stock A and Stock B, if you go back and buy Stock A again within 60 days, you can’t count any of those losses from your initial sale. So now you’re going to be stuck paying taxes on your gains from Stock B rather than them offsetting as you initially intended.

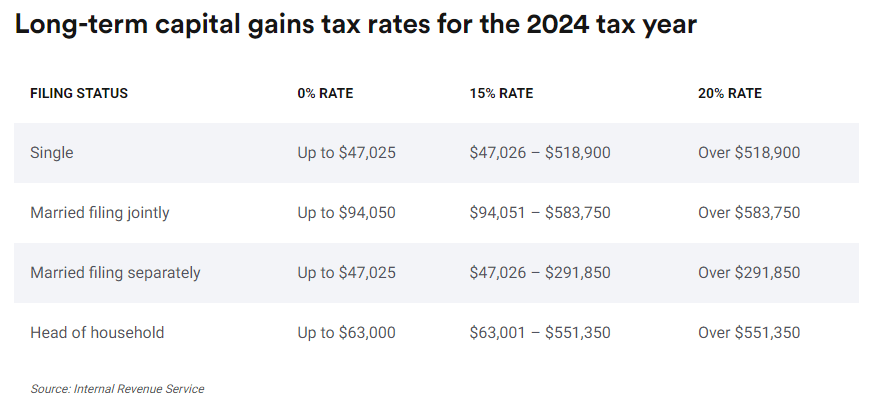

Another major concern is to ensure that when you attempt to lock in gains for Stock B, if you held it for less than one year, you will be subjected to short-term capital gains tax rates. These tax rates are far higher than long-term capital gains tax rates, which take place when you hold the stock for more than one year. You can see how low long-term capital gains tax rates can be below from Bankrate:

The best way to think about the impact that a wash sale might have on your taxes is this – you’re going to pay ordinary taxes despite realizing losses on the security that you bought.

My History With the Wash Sales Tax

The wash sale tax affected me quite frequently when I first started my investing journey because I thought that I could be a stock trader.

I won’t lie—I was someone who had Robinhood and would buy and sell stocks based on what the talking heads would say on CNBC. I was blindly buying and selling based on their recommendations, and while I could go on forever about how dumb the strategy was, the fact is that I was making foolish mistakes and trading in and out of the same few companies all the time.

At the end of the day, I lost a lot of money doing that, but I wasn’t able to write it off on my taxes because I was getting hit with the wash sale tax—the worst of both worlds!

Now, eventually, things will catch up and you can write off the tax in a future year, but the issue is that I was trying to get a tax advantage and sell some winners and offset those gains with some losses.

In other words, I completely messed up my tax strategy, which cost me. But guess what, I learned from it and here I am trying to teach you about the potential pitfalls to look out for!

How Can I Avoid Paying a Wash Sale Tax?

The simple answer is never attempt to tax-loss harvest and buy back into the same or a similar stock within 30 days of the sale.

In addition, don’t attempt to tax-loss harvest with a company that you believe in and want to own in the near future.

Tax-loss harvesting is incredibly powerful, so don’t let the wash sale tax scare you away entirely. Instead, simply see it as a part of the “game” that is investing – a rule you have to play by to maximize your success.

Sometimes, at the end of the year, I’m doing some “cleaning,” and there are stocks I no longer want to own. In that case, I will cut shares of that company instantly because I no longer believe in it. I won’t be in danger of the wash sale tax because I have no plans to buy back into that stock (or a similar one) anytime soon.

In addition, I have the mindset that if I believe in a company in the long term, I won’t sell any shares of its stock. Not only could I fall victim to the wash sales tax, but it would be far more work on my end and complicate my eventual taxes compared to simply holding on.

This all goes back to one of the pillars of the Investing for Beginners philosophy – value investing. Only invest in companies you see long-term value in. If you see that value, hold on through all of the short-term fluctuations in pursuit of long-term success.

Truthfully, I think tax-loss harvesting can be a powerful tool, but if you’re selling investments you want to be in, then you’re just gambling.

Sure, you might think, “I can sell my $AAPL shares now for $150 and hope that when I buy them back in 30 days, they’re not higher than $150.”

I get the thought here, but let’s break this down: If you think a stock is good enough for you to own for a long time, that means it’s going to theoretically go up over time, right? So, the odds of it going up in one month are greater than the odds of it going down, right?

So, if you do this, you’re once again letting the tax tail wag the dog – stop!

Tax-loss harvesting can be a very powerful tool, typically when you’re rebalancing or moving money from like funds into others, but not those that are identical. If you had to do something like this, I’d recommend buying an ETF specific to the stock you’re selling so you can still capture some of the general sector returns, such as selling FSLY and buying WCLD to capitalize on cloud computing.

Summary

The Wash Sale Tax is something that many people are unaware of when they get hit with it the first time, and sometimes many times after that. You might wonder why there’s a little ‘W’ next to the stock that you own when you log in to your broker but just stop worrying about it once you log out. Well, now you know.

And most importantly, hopefully, you should know some good ways to completely avoid the wash sale tax…the best way? Buy and hold stocks for the long term! And to do that, I recommend the Sather Research eLetter!

Related posts:

- A Free Calculator to Help You Calculate Your Dollar Cost Average Investments! Updated: 9/07/2023 One of the most beautiful things about dollar cost averaging (or “ratable lump sum investing”) is that you’re buying on a predetermined timeline....

- How To Best Reduce Investment Risk – A Comprehensive Framework Updated 4/21/2023 After much effort, you have finally mastered value investing. You now know how to identify good companies and value them. You also only...

- Portfolio Risk Management: 6 Strategies for the Retail Investor Risk management is an important element to achieving long-term investment results but it often gets overlooked by investors as generating returns takes center stage. Due...

- What’s the Best Way to Protect Your Investments? Stop Loss vs. Stop Limit Sometimes investing in the stock market can feel a little bit, “frothy”, per se, and when that occurs it’s nice to have something to fall...