When it comes to franchise risk, there are two sides to the coin—risk for the franchisee and risk for the franchisor. Whether considering operating as a franchisee or investing in a franchisor, it’s important to understand the intricate differences in these risks.

To do that, we will look at two examples of franchise risk gone wrong. In one situation, the franchisor went bankrupt. In the other, over 1,000 franchisees went bankrupt.

More specifically, we will analyze the following two events:

- The stock price disaster for Krispy Kreme Donuts

- The closings of 1,745 Pizza Hut Franchisee Restaurants

Both stories teach valuable lessons about the inherent risks in the franchise model, and that different outside forces contribute to the bearers of these risks and have distinct implications.

In this post, we’ll cover all of the following, and take lessons from history in order better understand the inherent risks with franchising:

- The Basics of the Franchise Model

- Basic Risks for the Franchisor

- Basic Risks for the Franchisee

- General Franchise Risk Can Vary Greatly

- Massive Franchisee Failures: Pizza Hut

- Franchisor Failure: Krispy Kreme Donuts

- Takeaway

First let’s review the basics of the franchise model, which is critical to understanding both the risks and drivers of success for both parties.

The Basics of the Franchise Model

Franchising is simple to understand when you examine its utilization in the restaurant industry; it is a very popular arrangement particularly in the QSR (Quick Service Restaurant) market.

In this model, a company such as McDonald’s holds the trademarks and intellectual property associated with their brand, McDonald’s, and is the franchisor. McDonald’s then allows other businesses to license their brand name and operate their own restaurants, and these businesses are the franchisees.

Franchisees will pay the franchisor fees for the right to license the brand name, typically as a percent of revenues (also known as a royalty).

Other common requirements to the franchisees include:

- A standardized menu

- Minimum quality standards

- Contribution to marketing

There can be variations to the above requirements—for example localized menus is common especially internationally and marketing arrangements can include varying mixes of franchisor spending and franchisee spending.

Most franchisees tend to be small business owners, but it is also common for a franchisee to be a large, even publicly traded, corporation. This is also particularly common in international markets.

The franchise model is a generally mutually beneficial arrangement, with each side taking own its own unique set of risks.

The franchisor benefits from not needing to operate restaurants to profit on its brand name. This greatly reduces expenses for the franchisor and can provide very good returns on capital for the company and its owners/ shareholders.

The franchisee benefits from being able to open a restaurant with an already established and successful brand name. Many times franchises have national or international recognition and customer demand, which takes much of the start up risk away for a new or established restaurant operator.

Basic Risks for the Franchisor

The franchisor takes the risk that is very common for companies as they grow in size; they risk the loss of control.

When you choose to franchise your concepts rather than operate them internally, you (generally) greatly increase the risk that outsiders will damage the brand you’ve worked so hard to build. Without a strict adherence to a quality control system, things can really get out of hand.

Depending on the franchise agreement(s), a franchisor could see its franchisees really flex their areas of freedom in ways that disappoint customers or employees who expect things to be a certain way.

On the flip side, more autonomy for franchisees can also generate a lot of creativity and spurn new growth avenues for the entire franchise system.

So you have risks and benefits with every franchise which can be specific to the entire franchise umbrella or even within each individual agreement.

And the level of control a franchisor exerts can also greatly differ even within QSRs in the same market. Parent companies like Starbucks choose to franchise some of their locations and directly operate others to close to a 50-50 split, while a company like Dunkin Donuts chooses to franchise out almost 100% of its locations instead.

Part of that decision comes down to the risks that restaurant operators face in each individual location, much of which is usually borne mostly by franchisees.

Basic Risks for the Franchisee

As for any restaurant or concept, just because the parent company (franchisor) has a successful brand doesn’t mean that every location will be profitable.

Franchisees usually are responsible for many of the expenses that accompany operating a location, such as:

- Rent to the landlord

- Paying the employees

- Buying ingredients

- Local advertising spending

And the demand for a concept can vary in many different locations because of things like:

- Demographics trends

- Real estate prices

- The state of the local economy

- Local and state taxes, etc

Some franchise agreements are more restrictive than others—a franchisor might require its franchisees to pay a minimum (or set) wage for its employees, or it may not.

I’ve seen some franchisors who have done a great job of shielding their franchisees from commodity price swings by entering into favorable contracts with suppliers which include hedges against large price swings, while I’ve seen others that leave that cost risk completely to the franchisee.

I’ve seen franchisors who force their franchisees to buy supplies directly from the franchisor or another supplier, while others have given their franchisees complete autonomy.

There’s benefits and risks to both sides of these kinds of supply chain dynamics; a franchisor buying for franchisees may be able to exert greater buying power and as a consequence reduce overall costs for the franchisees, while others may be forced into disadvantaged agreements depending on other factors.

General Franchise Risk Can Vary Greatly

It’s hard to cover every single possible risk for the franchisee but in general, because most franchise agreements today are based on a royalty on revenues, the risk/reward profile boils down to:

- Greater unit profit potential for franchisee

- Greater risk of loss for franchisee

- Less profit potential from individual locations for franchisor

- Less bankruptcy risk for franchisor from failing locations

But, you can’t take these extremes as a blanket statement for total franchise risk, as each agreement will have its variations and this contributes to different outcomes and risk exposures.

The franchisee/franchisor model is very much a symbiotic relationship, and as these parties treat each other well (or not), they generally participate in the spoils together, and fail together.

What risk means for each individual or company can vary, as well as each party’s goals and reasons for being in the business.

Usually a publicly traded corporation as franchisor has returns on capital as a primary focus. However, some publicly traded corporations focus more on empire building and revenue growth.

The same can be said for franchisees and small business owners, some operate purely for the bottom line, some operate for the freedom, and some to instill social good.

That means that the beneficial nature of any franchise agreement or system can be different things for different people and entities, so really diving into the details of each business model should be a requirement to adequately evaluating franchise risk.

Those deep dives into businesses is really what I do best, so we will do that now with two interesting franchising failures in the recent past—the Krispy Kreme Donuts parent company mismanagement and the closing of 1,745 Pizza Hut restaurants.

Massive Franchisee Failures: Pizza Hut

While it might seem unfair to have to have faced a pandemic, particularly if you are a restaurant which depended on foot traffic, these forces outside of our control are part of the risk of doing business.

Through no fault of their own, many restaurants and businesses across the world had to shut their doors completely as the pandemic and forced lockdowns eviscerated consumer demand for some places.

As many franchisees found out, this is the direct risk you take as a restaurant operator.

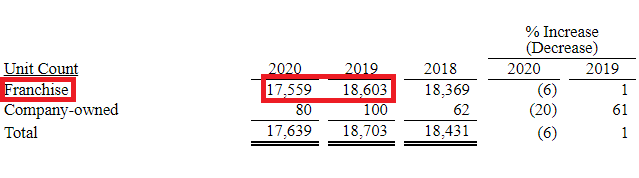

We can pull some stark data from Yum Brand’s annual report covering Fiscal Year 2020, which is the parent company/ franchisor for 4 popular concepts: KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and the Habit.

Showing the discriminatory and brutal nature of the pandemic, here are the statistics for number of stores between 2019 and 2020, in contrast to a concept like Taco Bell which actually saw an increase in total restaurants:

They further elaborate: “Pizza Hut experienced a net new unit decline of 1,064 restaurants in 2020, largely due to 1,745 global closures, including 867 closures in the U.S., nearly 300 of which were stores operated by NPC International, Inc. (“NPC”) as discussed in the following paragraph.”

You’ll notice in the screenshot that company owned stores closed down too, so it wasn’t like the franchisees were the only ones to take the fall here.

But in a telling truth of the franchise model itself, the operating profit for the Pizza Hut division of Yum Brands (the Pizza Hut franchisor) only lost -9% YOY, which is a stark contrast to having your whole restaurant go out of business.

While the pandemic was a freak black swan event, it highlights the sometimes uneven risks in franchising as it relates to the franchisee and franchisor.

The Pizza Hut brand itself is going to be just fine, and its shareholders taken aback with minor wounds, mostly because their Pizza Hut concept was 99% franchised and thus shielded from much of the bankruptcy risk.

However, that’s not to say that investing into a franchisor is a riskless adventure guaranteed of success, as we’ll see in the massive failure by the Krispy Kreme franchisor in operating its side of the business.

Franchisor Failure: Krispy Kreme Donuts

Krispy Kreme was one of the hottest IPOs in the new millennium, dazzling investors at a time that the stock market was undergoing a spectacular collapse after the dot com bubble.

On March 10, 2003, MarketWatch reported that the company’s stock was up 545% since the NASDAQ’s all-time high of 5,048 on March 10, 2000.

While this was a divine time for early Krispy Kreme shareholders, the party did not last.

On August, 26, 2004, the Street wrote that “Krispy Kreme’s transformation from growth stock to deep-value play made giant steps Thursday”, as the stock careened to $13.67 after almost reaching $40 earlier in the year.

According to publicly available company filings, Krispy Kreme (trading at the time as $KKD) saw its stock at a high of $39.99 in the Q1 for the fiscal year ending January 30, 2005 only to drop to a low for Q4 for the year ended January 29, 2006 at $3.35.

There are stock splits and stock dilution throughout the rocky history of Krispy Kreme’s publicly traded adventure, but eventually the company was taken private at around $1.35 billion in 2016.

Keep in mind that the $39.99 high in FY2005 Q1 represented a market capitalization of almost $2.5 billion, so essentially shareholders lost almost half of their investment over a decade+ long time period, with that rocky peak-to-trough period in 2005 representing a loss of 75%-80%.

That’s a huge failure even in a place as naturally volatile as the stock market.

So what happened?

To try and really dig out a detailed investigation, we will examine the last publicly filed annual report before the company’s stock collapse, which covered the 2004 fiscal year.

At the time, KKD had 357 total stores—141 were company operated and 216 were operated by franchisees.

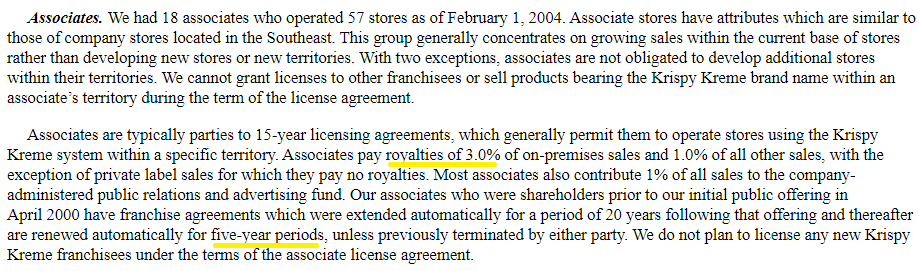

To understand the franchise agreements, we’ll turn to the Business overview of the annual report. Herein, their franchisees are referred to as “associates” and “area developers”.

The agreements with the associates looked pretty favorable for these franchisees, as we can see here:

The royalties there are pretty low, and the 5-year contract periods provide a decent time of stability for both parties.

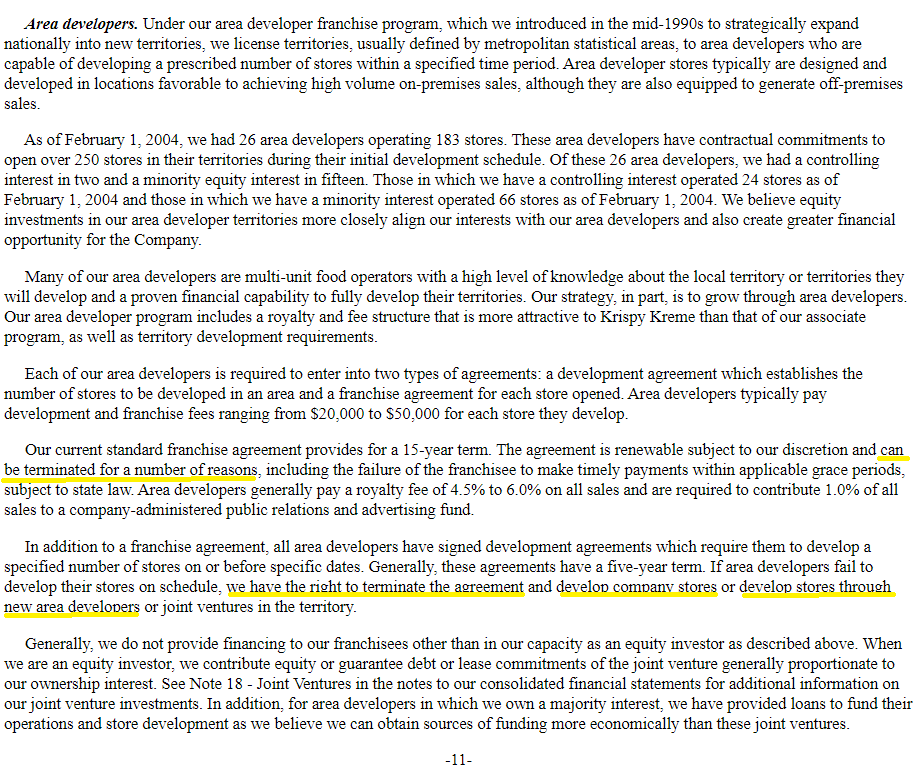

The area developer program on the other hand appears a little more suspect, at least potentially:

I highlighted a few key areas which made me raise my eyebrows. The disclosure of multiple termination clauses and strict adherence to a specific number of developments makes it seem like the franchise risks for these franchisees are tipped more on their side than the parent. The language makes them sound easily replaceable, which doesn’t sound like a true symbiotic partnership.

With 183 stores in operation by area developers, representing 51% of the parent company’s total stores, I’d find myself as an investor focusing on this aspect of the business, as it’s likely a huge driver to the franchisor’s future success.

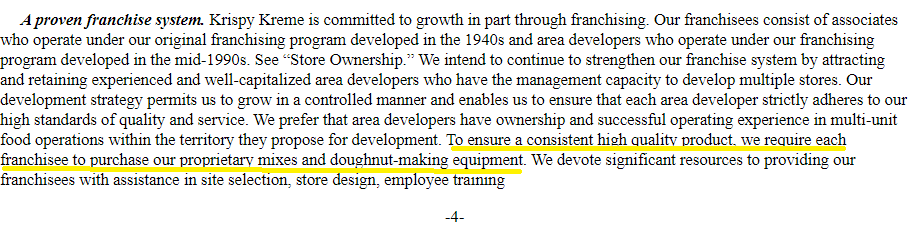

Another telling feature of Krispy Kreme’s franchise model was disclosed here:

Like we talked about earlier, this requirement by franchisees to have to purchase materials from the franchisor has its pros and cons, and by itself doesn’t necessarily mean the company or franchisees were doomed.

The franchisor reports these sales in their KKM&D segment, which management believes provides value to the system by providing the following competencies:

• Strong product knowledge and technical skills;

• Control of all critical production and distribution processes; and

• Collective buying power.

They admit to only having a single supplier for their key, unique glaze flavoring, and they did report working on finding another. Their raw materials are purchased on long term agreements using the commodity markets.

With all of this on its own, I don’t think a prospective investor in the KKD parent would necessarily have all the information to avoid such a growing company such as this (other than its expensive stock price).

Everything about the company looked healthy—from growing cash flows, revenues, profits, number of stores and system-wide sales.

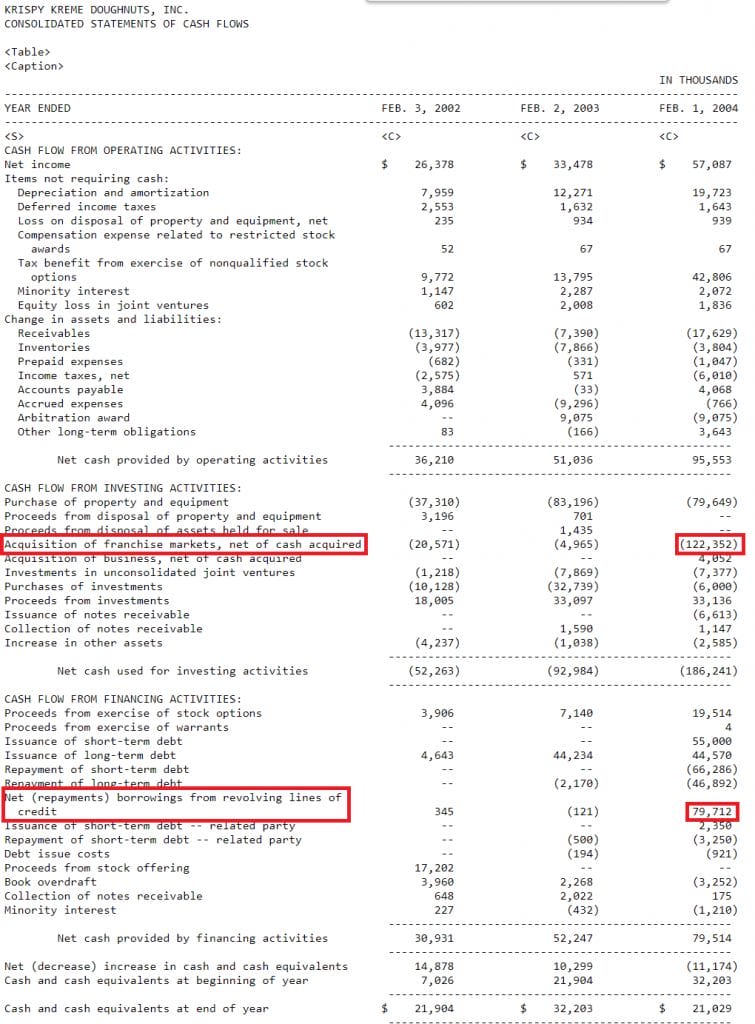

However, one little detail (from Exhibit 13 of their 10-k) provides what I’d consider a red flag, showing a very aggressive management (which became obvious later):

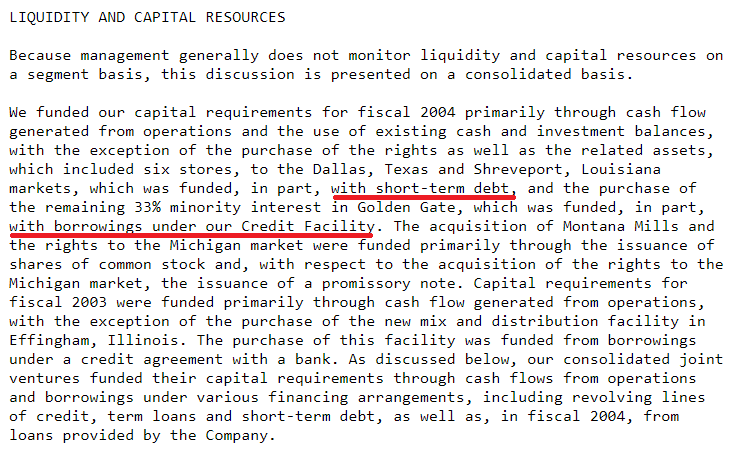

This takes some of a more advanced knowledge of accounting to catch this one, but notice the large acquisition and how the company chose to fund it.

For a company that generated around $15 million in free cash flow for FY2004, an acquisition of $122 million is pretty substantial. Not that this would necessarily be a problem if funded by attractive long term debt or share issuance, but the fact that they used a revolving line of credit is very concerning.

Why is a company growing at such a rapid pace so eager to aggressively expand that they would take out short term debt, likely at a huge interest rate, just to get rich faster?

Like the prudent and wise Warren Buffett once said, “Sound investing can make you very wealthy if you’re not in too big a hurry.”

By going to the MD&A, we can get more clarity on the situation:

They used this short term and revolving line of credit debt to acquire stores, but not just any stores, but stores from franchisees.

As they explained under operating results,

Additionally, eleven Area Developer and six Associate franchise stores became Company stores as a result of the Company’s acquisition of certain franchise markets in Kansas; Missouri; Dallas, Texas; Shreveport, Louisiana; Charlottesville, Virginia and Michigan…

The company also stated that a big portion of their huge sales and earnings growth for the year was attributable to these acquisitions.

It makes you wonder though.

- Why was KKD, the franchisor, acquiring stores from franchisees so aggressively, using high interest short term debt in order to get it done?

- What does that signal to franchisees?

- If the stores were obviously doing well that their acquisition contributed to such high growth for the parent, why become a franchisee if the franchisor is just going to take away your successful store?

With hindsight, it’s pretty obvious how short sighted a strategy like this is for the entire franchise model, which is a risk both investors and operators should’ve been aware of. Turned out that the CEO and CFO left the company shortly after the cookie started crumbling, and they were later found to be part of an accounting fraud which greatly contributed to the stock price collapse.

PR for the company was spinning on overdrive and blaming factors out of their control like the new low-carb diets of the time, but I think the truth was closer to short term gain for long term pain.

Companies that pillage their employees or franchisees will not usually have sustainable success, because when interests don’t align there are big roadblocks for long term success.

Takeaway

At the end of the day, no businessperson can completely eliminate the risks that come with operating, running, and investing in businesses.

However, some are more preventable than others, and many great falls and failures can be directly attributed to the people running the show.

When it comes to risk management, greed and overconfidence can cause businesspeople to throw caution to the wind, which works until it doesn’t.

You’ll see over and over again with business failures and bankruptcies that it was companies who were not conservative enough with their financial decisions who end up on the failure side of the list more often than not.

I think that makes for a fine lesson about risk for all of us…

Simply put, a lot of times, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Related posts:

- Systematic vs. Nonsystematic Risk Systematic and nonsystematic risks are pervasive concepts in the CFA curriculum and understanding them is critical to portfolio management concepts. The take away from this...

- How to Make Money with Stocks by Understanding Risk vs. Reward Myth #8 that Tony Robbins outlines in his book is that “You gotta take huge risks to get big rewards”. I’m sure that many of...

- Should Investors Care if a Stock gets Delisted? With all the fanfare going on in the news about Chinese stocks being delisted from U.S. exchanges, many investors are currently wondering what will happen...

- Investing in Biotechnology Companies: Pros and Cons Andrew and Dave recently talked about investing in Biotechnology Companies on their podcast and it was by far, one of my favorite episodes that they...