Benjamin Graham classifies the difference between the lay investor and the security analyst in order to give some direction to the “layman”, or average investor.

He saw a concerning trend within the security analysts of his day—more and more were using sophisticated math in order to justify high valuations on growth stocks.

Graham had a simple problem with this.

In order to justify high valuations, security analysts had to project growth far into the future and/or project high levels of growth in the future.

Notice the common theme there: both rely on the future.

Graham found it interesting (and concerning) that precise mathematics was being used on the very imprecise future. Any deviation from these projections could lead to a big discrepancy in the final valuations, which could lead to great losses on valuations where this error existed.

Perhaps it was within this problem that Graham saw an opportunity for the lay investor. At the very least, he wanted the lay investor to know this was going on and resist following the trend.

Before diving deeper, Graham lays out 2 important questions for the lay investor:

- What are the primary tests of safety of a corporate bond or preferred stock?

- What are the chief factors entering into the valuation of a common stock?

Security Analysis of Bonds

Ben Graham saw the general valuation model of bonds and preferred stocks to be more reliable from security analysts of his day because they relied on past earnings data.

He identifies the general approaches for security analysis of this kind:

- An earnings coverage test using past earnings data

- Minimum size requirement for the business

- A “cushion” stock/equity ratio comparing junior issues’ price and total debt

- Sufficient number of assets for utility, real estate, and investment companies

Then, Graham talks about some of the recent bankruptcies among railroad companies that didn’t pass some or all of the tests above. These examples showed how past financial data clearly outlined railroad companies that were “overbonded”, and thus risky investments.

This also happened in public utilities during the 1930’s, and the same safety tests could’ve been used to avoid the bad apples.

Security Analysis of Common Stocks

In this section of the chapter, Ben Graham outlines the way that security analysts generally make their analysis so that the lay investor can get an idea of the thought process involved.

He recognizes the ideal form of the security analysis of common stocks which some of you might recognize from the dcf formula, that is:

The valuation depends on (1) future cash flows and (2) a capitalization factor.

To make future estimates, the analyst takes a look at past data. Not only are past earnings considered, but also deeper metrics such as the operating margin, and industry specific metrics such as physical volume.

What I found surprising on this re-read of this chapter was that Graham looked at the difference between projections and results, specifically the Value Line forecast made in 1964 compared to 1968 results), and concluded that the projections were generally in-line.

He concedes that the forecasts for individual companies were often inaccurate and unreliable, but over an entire group the forecasts were more or less dependable.

It is for both of these reasons that diversification is practiced. Graham seems to support this, going on to say:

“For it is undoubtedly better to concentrate on one stock that you know is going to prove highly profitable, rather than dilute your results to a mediocre figure, merely for diversification’s sake. But this is not done, because it cannot be done dependably.”

–Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Capitalization Rate

After thinking about past earnings and projecting future earnings, the next step for both the lay investor or the security analyst is to determine the quality of the business. Graham offers 5 ideas for doing this:

- Having good long term prospects. High P/E doesn’t mean high future growth.

- Whether management is good. Most useful after a recent change.

- Having a strong balance sheet. Identified by looking at debt, cash, and assets.

- Great dividend track record. 20 years of consecutive dividends preferred.

- Providing enough dividends to investors. Not yield, but a payout ratio of ~67%.

Graham Valuation of Growth Stocks

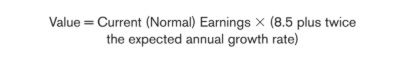

One of the lesser known Graham formulas is found in this chapter, and it’s how he attempts to put a valuation on a growth stock. Here it is:

Keep in mind that Graham expects an expected annual growth rate of 7- 10 years, not what’s projected for next year or the immediate short term future. He also posits that no business can grow indefinitely, which would value a stock as never too expensive (a value of infinity).

Instead: use a margin of safety with these calculations.

Finally, a key quote that’s overlooked by many value investors (in my opinion):

“We should point out that any “scientific” or at least reasonably dependable, stock evaluation based on anticipated future results must take future interest rates into account.”

–Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Industry Analysis

The summary of this short section is that basically, industry projections are generally not very practical. It’s hard to find an analysis that’s against the grain, meaning a bearish outlook on an industry that has done well lately or a bullish outlook on an industry that has struggled.

Wall Street is notoriously fickle.

In this section Graham also tells the lay investor that you’ll have to pick a side.

Either be happy with conservative calculations with a margin of safety that’ll lead to missing out on big opportunities, or have aggressive estimates and run into stocks that fall severely. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Wrapping up this Chapter Summary

Graham finishes by recommending a two part appraisal process:

- Past performance value assuming the past will continue into the future

- Adjusting the valuation based on expectations of future catalysts or changes

I think this is a great way to wrap up how the lay investor can look at making analyses of individual stocks for a portfolio.

There should be:

- A look at past performance and analysis of that financial data

- Broad projections on a company’s future which can adjust the valuation

- A great margin of safety—from both a price paid to valuation standpoint and on adjustments made based on projections or future expectations

Related posts:

- Defensive Investors: Rules from the Classic Book, The Intelligent Investor Updated 4/21/2023 In the 14th chapter of Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham outlines his seven criteria for defensive investors. The Intelligent Investor, considered by many as...

- The Intelligent Investor: Is it Outdated? Is it for Beginners? Should I Read it? Edited 3/24/2023 Warren Buffett started learning about investing when he was seven or eight. I know a late bloomer. Buffett’s father started a small investment...

- The Enterprising Investor Portfolio Policy – Ch 7 of The Intelligent Investor Benjamin Graham defines the enterprising investor as someone who will “devote a fair amount of his attention and efforts toward obtaining a better than run-of-the-mill...

- Irrational Exuberance: A Book Review Updated 6/24/2023 Irrational exuberance refers to extreme behavior enthusiasm, often compared to the stock market and investor behavior. Typically, it means investors are excited and...