Deferred income taxes in a company’s consolidated balance sheet and cash flow statement is an easy concept in principle, but when deferred income tax liabilities (or assets) change from year to year, that’s where it can get more confusing.

The reason for deferred income tax liabilities and assets in the first place is because of the basics of GAAP accounting—meaning that sometimes accounting on a GAAP basis doesn’t match the actual cash transactions.

Said more simply, GAAP accounting isn’t always the same as business accounting.

GAAP is one method to try and understand a business’s financials and accounting, but can differ materially from a business’s cash outlays or inflows, which is why it’s important to get an intuitive feel for the relationship between the income statement and cash flow statement, or balance sheet, or any combination in between. It doesn’t need to happen all at once, and it won’t always apply, but comprehending deferred taxes is another step towards that important mastery for fundamental analysis.

When it comes to taxes and accounting, those also don’t always reconcile. The IRS doesn’t care about GAAP, they just want their money, and their rules can be different from GAAP.

Let’s take 3 examples of that:

- A real-life example using personal finances and taxes

- An example of deferred tax liabilities differing from GAAP accounting

- How to find (cash flow statement and footnotes) with $CVX

Understanding the IRS vs GAAP in Real Life Personal Finances

Those of you who’ve had a mortgage before know the significant tax benefits that can accrue as you pay back on the loan.

(While less applicable in recent days due to the increase of the standard deduction, those who itemize or have itemized in the past should get this reference).

If you itemize, any interest you pay on a mortgage is tax deductible.

So as an example:

If you made $75,000 in a year and paid $6,000 in interest on your mortgage, you would be taxed on an income of $69,000 instead of $75,000 because of the $6,000 interest deduction.

Now, that’s not a savings of $6,000 of taxes, but rather, a savings on the difference of taxes of paying on an adjusted $69,000 income instead of your real $75,000.

Let’s say you were planning a monthly budget—one form of accounting.

According to the budget, if you were an astute tax shrewd, you could allocate a smaller withdrawal from your paycheck withholdings to adjust for this planned mortgage deduction, to get your cash immediately instead of waiting for the annual tax return.

The reality is that this kind of a monthly budget is more of a “real time” accounting.

Since you don’t owe the taxes until the April tax season, you can increase your cash flows in the short term to maximize your deduction instead of wait. Your “GAAP” or monthly accounting method is different than what really happened with the IRS—the IRS got paid once in the year, not every month—but because you understand tax laws and the benefits of immediate cash you could make a plan.

An Example of Deferred Tax Liabilities Differing from GAAP Accounting

In the same token, how businesses treat tax deductions and how the IRS treats them (or gets paid) can also differ. Sometimes by a lot.

One example is the tax deduction on a large capital expenditure.

Capex is when a business buys an asset—like plant, property, or equipment—to fuel future growth and earnings. As investors know, new assets must be depreciated over time in GAAP. Depreciation is required on assets that are known to eventually decrease in value over time, and for GAAP, is done over time to smooth out earnings.

However, for the IRS, they’ll take your depreciation all upfront. Meaning, the IRS will place a deduction on the expense (Capex) in the same year it’s transacted (Code Section 179).

The implications for the business are that the taxes they pay during a large capital expenditure reduce their taxable income in that same year, while on a GAAP standard their income is reported much higher because the expense to the income will be depreciated over the life of the asset.

So, that means that future income will be higher than GAAP income, since the IRS deduction was taken up front—which paves the way for deferred tax liabilities.

Deferred tax liabilities simply create a GAAP accounting work-around (and a good one) to represent the additional taxes they will owe from a higher taxable income in the future due to them taking the real (or “book”) depreciation deduction from IRS all upfront.

General takeaway: That means that after a large capital expenditure, you should also see a large increase in deferred income tax liabilities (in the balance sheet) to reflect the short term difference between cash paid for taxes and cash owed for taxes in the future.

That also means that not only should you see an increase in deferred tax liabilities in the balance sheet, but you should also see more cash in the cash flow statement due to that upfront deduction.

It might seem kind of backwards, after all depreciation is usually added year over year in the cash flow statement. The cash gets spent once, a big immediate outflow in the cash flow statement (if financed by cash), followed by additions to the cash flow statement on GAAP expenses (depreciation) that are non-cash.

But because we are talking about a tax deduction, the “inflow” of cash (or cash savings) happens all at once, and then will be expensed from future years as cash outflows as (IRS) taxable income increases.

Real Life 10-k Example: Chevron $CVX

The reasons for a company having the ability to take a deferred tax liability can vary, and can honestly be hard to quantify in detail, let alone predict, as an outsider.

Because companies have entire teams dedicated to taxes and taking advantage of tax deferrals and other beneficial methods of handling accounting, investors should be able to trust the judgement applied in quantifying this assets as a general rule.

At least for our purposes, financial statements should make it clear how the usage of deferred tax liabilities are being implemented, and we should understand those potential impacts to reported free cash flows and earnings.

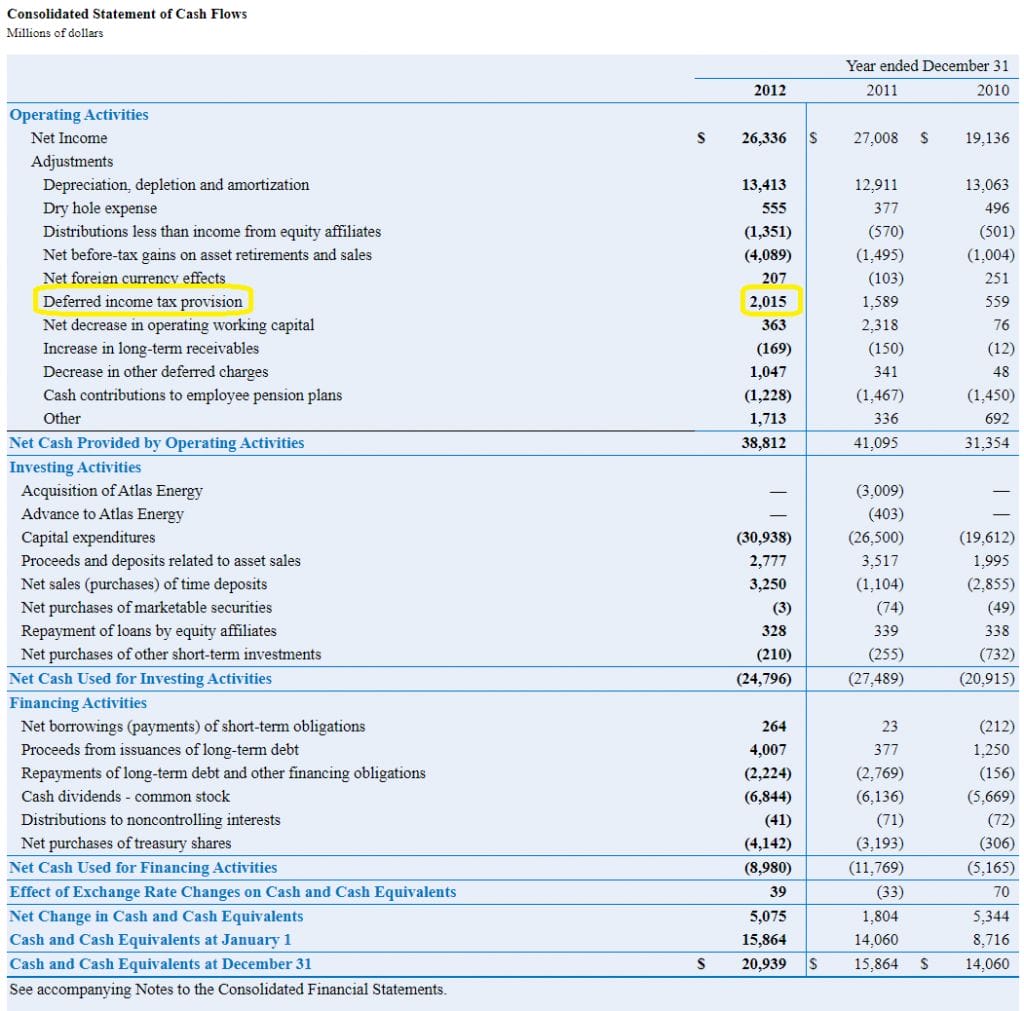

I’ll take a 10-k from $CVX all the way back from 2013, when they reported a somewhat significant tax deferred liability of $2,015 million.

We can see the deferred tax liabilty in the cash flow statement:

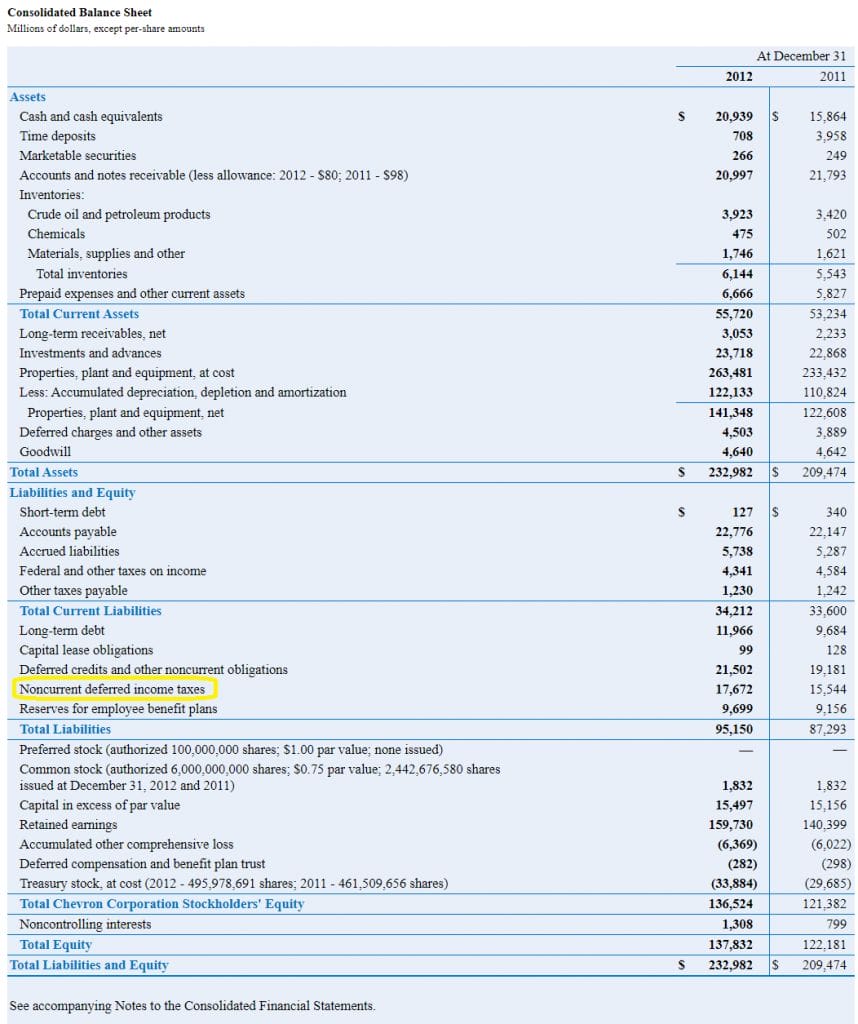

We can also see the total deferred tax liability on the balance sheet, which represents future obligations that will reduce cash flow and is quantified precisely here:

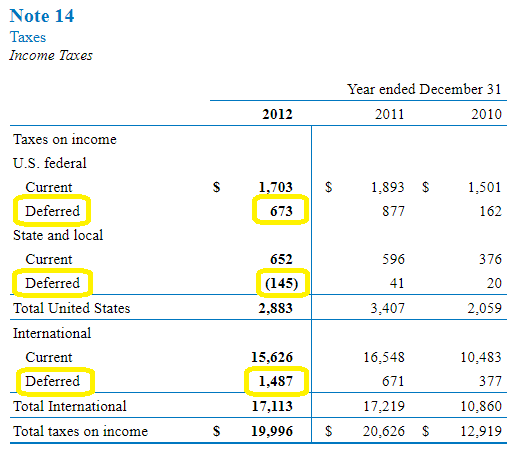

Finally, if you take a look into the footnotes of the 10-k you can usually see a good description of the deferred tax liabilities or assets, as split between U.S. taxes and international taxes, for example:

Summing the deferred liabilities for each of those categories, we also see that they sum to the $2,015 million addition we saw in the cash flow statement: $673 – $145 + $1,487 = $2,015.

Investor Takeaway

As it stands, understanding deferred tax liabilties is another great tool to have under the belt, particularly at times when they make up a larger portion of Cash from Operating Activities, or just Free Cash Flow or Net Income in general.

They could possibly be used in forecasting future earnings or cash flows as well, if used correctly.

Combining this with the understanding of how other footnotes impact financials and a mastery in learning how to interpret a 10-k can go a very long way towards long term success in forecasting and analysis.

Andrew Sather

Andrew has always believed that average investors have so much potential to build wealth, through the power of patience, a long-term mindset, and compound interest.

Related posts:

- GAAP Accounting Rules: The 4 Basic Principles Investors Should Know Most think of Accounting as this dry profession we only need to consider around tax time, but as an investor, understanding how accounting works on...

- (NOL) Net Operating Loss Carryforward Explained: Losses Become Assets In contrast to deferred tax liabilities, a net operating loss (NOL) carryforward is a number that can be used to offset future Net Income, which...

- Deferred Revenue: Debit or Credit and its Flow Through the Financials Basic accounting for public companies can get confusing with different terms that mean the same thing (like deferred and unearned revenue), vs opaque definitions (such...

- Simple Balance Sheet Structure Breakdown (by Each Component) Updated 6/3/2024 “Never invest in a company without understanding its finances. The biggest losses in stocks come from companies with poor balance sheets.” Peter Lynch...