Some of the greatest value investors of all-time have used special situation investing to attain superior returns in the stock market. The average investor can also find opportunities in special situations, usually by combining it with stocks that are cheap.

I mentioned Warren Buffett, and I think most people actually aren’t aware that he used special situation investing throughout his time managing Buffett Partnership Ltd, where he achieved 31.6% CAGR and beat the Dow by over 20% annually.

We’ll get into those specifics later. In this post, we’ll cover the following:

- Background: Major Corporate Actions

- The Basics of Spinoffs

- Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A)

- Warren Buffett’s Special Situation Investing Strategy

- “Undervalued Generals” and “Work-outs”

Personally, I think investing in special situations should be a strategy implemented primarily by value investors instead of growth investors, but let’s cover the basics either way.

Background: Major Corporate Actions

As corporations grow and create profits, they also involve themselves from time-to-time in financial transactions that are seen as creating shareholder value to the firm.

I think it’s easy to think of special situations in relation to the major services provided by an investment bank.

One type of transaction involving investment banks that most every public company today has participated in is the IPO, or Initial Public Offering.

In these transactions, companies employ an investment banker like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley to issue shares of equity in order to raise capital for early investors. This access to capital is what makes the wheels of capitalism run smoothly, and is how companies have been able to scale and grow so spectacularly in a very short period of time.

What Are Special Situations?

Special situations are simply some of the major transactions that create foundational shifts in corporate and ownership structure. These are usually seen as unlocking shareholder value and/or catalyzing growth. Two very common ones include:

- Spin-offs

- Mergers and Acquisitions

In both of these special situations, company ownership is undergoing drastic change. In the first, ownership is fragmenting into two separate companies; in the second, two companies and ownerships are combining.

The Basics of Spinoffs

In a spinoff, a company essentially takes part of its company and spins it off into a completely new one, divesting assets, liabilities, and earnings and revenue streams. The spun off company becomes its own company, with its own management and publicly traded shares.

When a company announces a spinoff, there will usually be a “parent company” and its spinoff (or “spin-co”). Shareholders of the parent will receive shares of the new company and the spin-co, at which point they can decide to hang on to both, sell both, or sell one or the other.

Interestingly, the two separated companies can actually sort-of share the previous company’s brand name as the transition takes place.

For example, when the Hewlett-Packard Company split its server manufacturing and services company with its printer and desktop company, the two new companies maintained parts of the HP/Hewlett Packard name. The server/cloud company got to keep the Hewlett Packard name rebranded as Hewlett Packard Enterprises, or HPE, and the desktop and printer company got to keep the HP as simply, HP Inc.

When a spinoff is announced, it is usually revealed in the parent company’s press release (8-K). From there, the company will file an S4 and 10-12B, after which the separated companies will each file their regular financial documents (10-K, 10-Q) in the fiscal periods to follow.

These documents can contain valuable snippets of information on whether special situation investing opportunities exist within the securities offered or about to be offered.

Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A)

Companies will frequently use acquisitions as a long term strategy for growing a business.

You’ll often see the frequency of M&A increase as the market for an industry matures, as a matured market usually leaves less opportunity for high returns from reinvestment, and so industry leaders will have to look to buy their way into new growth.

When one company acquires the other, they gain ownership of all aspects of the acquired company’s business—the assets, cash, profits, trademarks, etc.

Acquirers can pay cash, issue debt, or issue shares in order to buy another business outright.

Shareholders in the acquired company will get paid out either in cash, or in shares of the acquiring company, or some combination of both.

At the end of the transaction, the acquired company’s shares will cease trading while the acquirer goes on with its business with a shiny new (and hopefully growing) addition to its umbrella.

An acquirer can involve itself as minimally or maximally into the operations and financials of an acquired company as much as it pleases. After all, the acquired company is now the property of the parent (acquirer).

We can look to Warren Buffett again as an example of how an acquirer might act in this process. With basically all of the businesses which are acquired under the Berkshire Hathaway umbrella, Buffett allows the former management to stay in place and for the underlying businesses to remain exactly the same, with their only requirement to direct their profits to the parent (Berkshire).

Other ways that companies have treated their acquired companies involve gut wrenching staff reductions, management overhauls, and even complete changes to their ways of doing business. Unfortunately, that’s just the nature of business, and it can lead to significant synergies and advantages to the parent company.

M&A can tend to happen at a price premium compared to a (would-be) acquired company’s value in the market.

So, when acquisitions are announced, there tends to be a jump in the (about-to-be) acquired company’s share prices—to match the offer at hand.

Even if all shareholders don’t like the deal presented, there’s a market full of arbitrage traders who can find quick stock market gains by exploiting an undervalued share price compared to a proposed deal price.

In order for an M&A to be approved, a majority of shareholders with voting power need to approve the deal (at least as most corporate governance systems are set up).

Also, there will often have to be approvals by regulators such as the Federal Trade Commission, who needs to ensure there are no anti-trust or monopolistic consequences of an acquisition, conflicts of interest, or any other good reasons to invalidate the proposed transaction.

An example of a proposed acquisition in recent history which was not approved was the hostile takeover bid of Qualcomm by rival Broadcom.

Two Important Aspects of M&A

Noting that an acquirer can do what it pleases once an acquisition deal has completed, an acquirer can take on the name of its new subsidiary, such as what Avago Technologies did after acquiring Broadcom– changing the name of the parent company to Broadcom Inc while keep its original ticker ($AVGO).

Transactions involving these types of organizational changes can be tricky to the bypassing observer, which is why it’s important to read the Business Ownership section of a company’s 10-K when analyzing special situations to get the background knowledge of a company’s structure.

Note also that a “merger” is not really a merger in the sense that the new company is a 50-50 joint venture. In a merger, there is always an acquirer and an acquired, even if the companies are close to the same size.

One company and its shareholders will always retain ownership of the parent company, and one will be acquired, though the names can be changed as we learned from the Avago example above.

But, when a merger is completed using shares (where an acquired company’s shareholder receive shares in the acquirer as payment), there can be a major shift in the final ownership percentages. A major shareholder in the acquired company can remain a major shareholder in the post-transaction parent company, though probably to a reduced extent due to the dilution from the combination of shareholder bases of the two companies.

Warren Buffett’s Special Situation Investing Strategy

There are other special situations which I’m sure that investors have used to generate alpha (outperformance) in the market, but we’re just going to focus on these two major ones today.

Going back to Warren Buffett, it’s not widely shared, but a huge part of his portfolio in the 1950s was comprised of the types of companies (“undervalued generals”) which were likely to experience special situations such as spinoffs and/or M&A (Buffett called it “coattail riding”). And his second biggest portion of his portfolio throughout the late 1950’s was also explicitly comprised of special situation type stocks, which he referred to as “work-outs.”

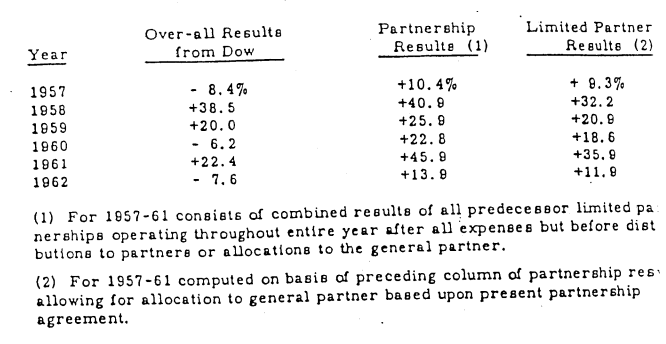

Look at Buffett’s performance against the Dow during the partnership days to see how powerful his special situation investing strategy was:

The reason why I’m so jazzed about this particular time period for Buffett is that he was able to create outsized returns in years where the market did not perform well.

Sure, we all know about his great performance with Coca-Cola, GEICO, and other great picks like American Express, the Washington Post, and lately Apple—but most of these investments were made at a time when interest rates were falling and the stock market was zooming (before the word zooming was even a verb).

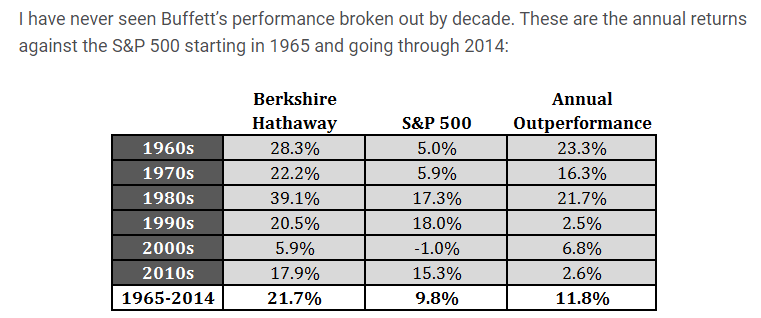

I like this illustration by Ben Carlson, CFA showing just how different the decades were:

I’m fascinated by the 1950s and 1960s period of Buffett’s career because these were times where interest rates were going up, and the Dow averaged well below 5% annually.

From about 1987 on, when Buffett famously loaded up on Coca-Cola stock, interest rates have been on a steady decline and growth investing strategies have performed really well in the interim.

Looking at a period like today, where I’m writing this in 2021 and interest rates on the 10 year US treasury are trading around a ridiculously low 1%, it seems inevitable that interest rates will have to experience a rising trend eventually, even if the Fed is committed to keep rates low through 2023.

“Undervalued Generals” and “Work-outs”

So how did Buffett do it?

In the “Ground Rules” sent out as a letter to partners in 1963, Buffett revealed two types of investing strategies which ended up making a significant part of his stock allocations over the life of the partnership:

- Undervalued generals

- Work-outs

Note that near the end of his partnership, Buffett switched to a more concentrated portfolio approach (holding American Express as a 40% position), and continued a concentrated approach with other more growth-type stocks like Coca-Cola and GEICO.

Both undervalued generals and work-outs, on the other hand, were more focused on value-type stocks that were later fondly termed “cigar butts”—wherein an investor finds a free cigar butt on the ground with one or two puffs left, and then discards it.

And interestingly, these value-type stocks relied heavily on special situations in order to unlock the value of underutilized assets and make a cigar butt type approach effective.

#1 – Undervalued Generals

From Buffett’s own words on the undervalued generals (bolded emphasis mine):

“Many times generals represent a form of “coattail riding” where we feel the dominating stockholder group has plans for the conversion of unprofitable or under-utilized assets to a better use. We have done that ourselves in Sanborn and Dempster, but everything else equal, we would rather let others do the work.”

Note that “dominating stockholder group” is what we call “activist investors” today, and oftentimes these activists will pressure companies to embark on special situations—such as mergers, spinoffs, or divestitures—in order to unlock hidden shareholder value and propel higher stock prices.

Ironically, or maybe not so ironically, Buffett became a corporate raider himself as he bought up the stock of Berkshire Hathaway, eventually pushing out management and selling low return assets.

Investor Application: We can use a value investing approach while also searching for major investors with large stock positions, and hope that they will pressure management to unlock value for us sooner rather than later.

Simply watching for these types of activists and when they accumulate stock can increase the chances that a company will mean revert in the months, rather than years, to come.

Not only can activists advocate for mergers or spinoffs, but they can also pressure a company to butter up its operations for a takeover bid, which as explained earlier, tends to come with a significant price premium for the shareholders of acquired companies.

#2 – Work-outs

Now, as Buffett describes “work-outs,” we can see an obvious application of special situation investing:

“Our second category consists of “work-outs.” These are securities whose financial results depend on corporate action rather than supply and demand factors created by buyers and sellers of securities. In other words, they are securities with a timetable where we can predict, within reasonable error limits, when we will get how much and what might upset the applecart. Corporate events such as mergers, liquidations, reorganizations, spin-offs, etc., lead to work-outs.”

Note that Buffett had up to 40% of his portfolio in work-outs at certain times of his partnership, but those opportunities became less prevalent as time went on.

Investor Takeaway

The benefits to this kind of special situation investing is that, as Buffett put it, the gains can be relatively stable when you know what you are doing.

By digging into deeper research—by reading the 8-K’s, proxy statements, and the 10-12B for spinoffs—we can find companies with deep hidden values which might not be showing up in the balance sheet or income statements.

While there’s no doubt an intense focus on special situation investing by institutional investors and other professionals, there’s also a lot of algorithmic trading and ETF theme investing going on at high transaction volumes where hidden value is not being looked for past the financial statement figures.

Diligent investors looking to implement a value investing approach, particularly if related to the traditional Benjamin Graham “cigar butts,” can increase their chances of finding quick mean reversion rather than years of “dead money,” in the minefield that can be deep value stocks.

Post updated: 1/14/2023

Andrew Sather

Andrew has always believed that average investors have so much potential to build wealth, through the power of patience, a long-term mindset, and compound interest.

Related posts:

- How to Find Acquisition Candidates – Two Perfect Real Life Examples M&A can be a huge value driver for both the acquiror and acquired if it unlocks larger future growth or leads to synergistic cost efficiencies....

- Franchise Risk: Two Public Failures Explain the Two Sides of the Story When it comes to franchise risk, there are two sides to the coin—risk for the franchisee and risk for the franchisor. Whether considering operating as...

- Here’s the Optimal Dividend Policy According to Warren Buffett As I continue to read (and fall in love with) The Essays of Warren Buffett I can’t help but urge you to buy this book...

- My Thoughts After 10 Interviews on a Prudent Buy and Hold Strategy If there’s one thing many investors can all agree upon, it’s that buying stocks and holding for the long term is the best way to...