The theory of dividends has long been disputed. As interest rates have declined, dividends have become less attractive. As growth stocks have reigned supreme, dividends have taken the backseat.

In today’s fast, high, and big tech world, we need to reconsider dividend theory.

Shareholders need to push companies, like the big 4 tech companies, to pay dividends as their moral duty.

I’m not saying this altruistically—this ongoing movement away from dividends is sowing the seeds of value destruction for many years to come.

There are several moving parts which are making this clear:

- Company lifecycles

- The undeniable upper limits on:

- Reinvestment

- Entrepreneurship

- M&A

- Stock buybacks

But shareholders aren’t focusing on these.

People, it’s about time to wake up and think about dividends again. My theory on dividends is that there’s a morality about them. Dividends are good. And big tech needs to starting think about them.

To understand why, let me take you through the dreaded upper limits in business.

Company Lifecycles and the Upper Limit

Companies MUST pay dividends at some point because of two universal truths:

- All companies have a life cycle

- The sky is NOT the limit

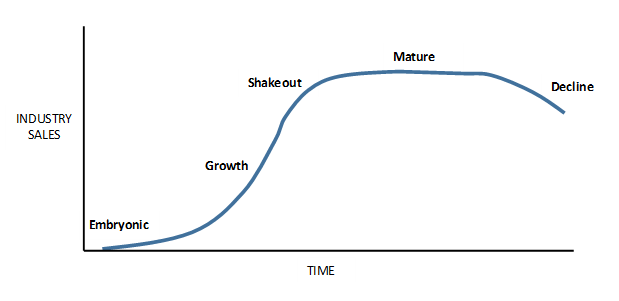

Every company has a lifecycle which relates to the industries or markets in which they transact business. As business schools teach (and our contributor Cameron Smith so eloquently described), industries follow the following predictable lifecycle:

And the primary reality, as described above, is that the sky is NOT the limit. There are only so many people in the world, and only so many potential clients/ customers.

A market can grow as the population it serves grows. A market can also grow through pricing power. However, the upper limit to pricing increases is generally constrained to actual value added, which presumably also has its own limit.

These two limiting factors contribute to a company’s Total Addressable Market, and creates an upper limit on its growth, forcing growth to saturate and slow.

This maturation in growth of a Total Addressable Market is experienced as a new market displaces an old. Older more mature markets are likely to have hit a saturation of growth long ago. As the new market displaces the old, exponential growth is experienced, as seen in the Embryonic and Growth stages.

Few markets create entirely new spending channels, and even those that do must eventually saturate to the dual upper limits of population and pricing growth.

This maturation of markets makes it way down into an industry, which makes its way into the individual companies within those industries.

Here’s the key—the reason you might see a company continue a high growth path despite a matured industry is twofold, either:

- The company is a new disruptor and takes market share exponentially from incumbents

- The company enters a completely different market and experiences exponential growth there

No company can grow market share above 100%. The more market share a company attains, the less incremental growth is possible from taking additional share.

And by the way, no company can grow its prices to infinity either. Price increases will be rejected by the market at a certain point, no matter how attractive a product or service. At its most extreme, a company’s growth is constrained by overall GDP, as no company can grow above this.

This reality, of a company reaching matured growth eventually, is the first reason why dividends must be on the table.

Reinvesting capital to try and capture growth rates above maturation are likely to be value destructive, which is the second reason for the morality of dividends.

Reinvesting Capital vs Paying a Dividend

“Companies that reinvest capital and earn extremely high returns on that capital should reinvest all capital into the business for future growth rather than pay some of it out in a dividend”.

–Everybody, circa 2021

This argument makes logical sense and does apply to many businesses, particularly those in the growth stage.

The logic is not hard to follow—a company that can earn a 20% return on its capital would be foolish to return that capital as a dividend to investors who might be lucky to earn 10% on it; the increase in value accretive to the company does more to the shareholder rather than the cash received, which maybe earns 10% instead of the 20%.

The problem with this statement is that it does not consider the lifecycle reality of companies.

Companies that have historically earned 20% on their capital are not guaranteed to earn that forever.

Past success doesn’t guarantee future success.

The fact of the matter is that the (consumer/b2b) market doesn’t care about your (the company’s) historical rates of return. If demand for a product or service has an upward limit, so do the returns on capital for businesses in that industry.

Take Facebook as an example.

At a certain point, the majority of the world will eventually all own smartphones. At a certain point, the majority of the world’s population will probably have considered a Facebook account. At a certain point, the majority of businesses will have already tried, or will be, advertising on Facebook.

The upward bounds on Facebook’s growth are the population growth of the world, the population growth of the number of businesses in the world, and the aggregate spending of businesses in the world.

As long as Facebook is far away from any of those three constraining upward limits, the company is likely to earn high rates of return on its capital by gaining share of potential customers.

Competition aside—it would likely be able to continue its ability to earn the same rates of return as it historically did, at least for the most part.

However, once that point of maturation approaches, reinvestment in lieu of dividends is more and more likely to start to become value destructive.

Rates of return on capital must come down as a company’s growth matures.

If those rates come down enough, then dividends (or share buybacks) would’ve been better stewardship of capital for shareholders.

You might say that Facebook should just reinvest in adjacent markets to sustain high growth.

That is where the next problem arises, another reality of the business world which speaks to the moral imperative of dividends.

Capital and Entrepreneurship

Many businesses continue to learn the hard way that’s it’s very hard to buy your way into new markets.

In a market where incumbents are not interested in being acquired, it can be very hard for a new entrant to aggressively take share, even with huge infusions of capital.

If you don’t believe me, then why is success rate of venture capital is so overwhelming poor?

You can argue that most VC investments are directed at young and emerging industries… fine.

But even stealing market share in matured industries is particularly difficult even with huge amounts of capital.

You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

If your company has such a high rate of return on its capital, it’s likely because of a strong economic moat.

To achieve similarly high rates of return on capital in other matured industries, it’s likely that the incumbents also have their own strong economic moats.

Many moats, especially today, are not strong because of the amount of capital invested or supporting the business—rather from some intrinsic and unique factor.

Big businesses, especially in tech, have embarked on many expensive ventures and had nothing to show for it.

These are value destructive, and likely would have been better paid as a dividend to shareholders.

If you must have an entrance in a new market to sustain high rates of return on capital and explosive growth, and a successful entrance proves to be difficult and probabilistically unsuccessful, then returning the capital to shareholders provides a better probabilistic outcome for these shareholders.

I’m not saying that companies shouldn’t innovate into new markets. They should… but with a healthy balance and while allowing shareholders to participate in the fruits of past labor… through dividends. It’s most definitely a fine balance.

The problem is that high powered founders and executives carry with them the hubris of past success, and this can lead to arrogant allocation of capital.

Rather than properly distribute cash to shareholders in recognition of the reality, that their growth path is saturated and the prospects of new ventures uncertain, these winners go on to destroy capital. Naive shareholders only exacerbate the problem, standing behind them and cheering them on.

Example in Fintech

From the outside looking in, I think Square’s entrance into P2P transfers with the Cash App could be a good example of this.

It is no question that Venmo has been the undisputed leader in convenient P2P transfers on a smartphone.

I’m 32. Around the time I first started using Venmo, it was only those older than me who didn’t already have the app. Everybody around my age and younger had Venmo, except 1 person I can think of.

Anytime I needed to give a friend money, I used Venmo, because everybody else uses it too.

Venmo has a strong network effect as a moat around it.

The added friction of potentially having myself or another friend needing to download a different app instead of Venmo makes a switch away from the app highly unlikely, especially because it is free as long as I don’t need to use their extra services.

No matter how much capital Square puts into marketing their Cash app, they cannot get around this reality with consumers for as long as this point remains true.

They might have impressive growth numbers now, which is easy when you start with a small base, but to overtake Venmo with significant market share would be increasingly difficult.

If Square had a rational shareholder base concerned with prudent capital allocation, and was seeing symptoms of maturity in its core business, then they should demand a return of some capital to shareholders—rather than see the company destroy all of it in a market that is unlikely (probabilistically) to succeed.

It’s akin to the gambler on a hot streak, rather than pocket some winnings he doubles down again and again, until he leaves empty handed.

M&A Versus Dividend Payments

The next logical argument is that companies should use bolt-on acquisitions to grow their business and continue earnings high rates of return on their capital through M&A.

There are certainly master acquirers throughout the business world—those who opportunistically scoop up businesses at great prices and/or with synergistically with their core businesses.

However, these high rates of return through M&A necessarily have their own upper limit.

Of course you have the whole trouble with fair trade and antitrust. But there’s also a shrinking number of opportunistic acquisitions available the more and more capital you accumulate. Just as Warren Buffett or Bill Ackman and they’ll wax poetic about it.

And then you have the fact that probabilistically, M&A is a poor choice for reinvesting capital.

As my business partner and co-host Dave Ahern has uncovered, most mergers and acquisitions actually destroy capital rather than prove accretive. The number has been determined to be as high as 70%-90% from reputable sources.

Continually doing M&A rather than paying a dividend has another natural upper bound to it.

At a certain point, the sky IS the limit. And at a certain point, with decreasing supply of good opportunities, M&A becomes the gambler’s demise.

And it’s likely for humans, with our infinite optimism and hubris, to expect that upper limit (as shareholders and management) to be farther into the future than reality is dictating.

Good managers have the humility to recognize that, and pay that “kiss of death” dividend, where you “kiss and say goodbye” to your company’s youth and growth.

Just Buyback the Shares Then. After All, it’s Tax Efficient

The anti-dividend rhetoric might be the strongest among those who argue that the tax advantages of buybacks make dividends a less sophisticated, and so obviously less attractive, way of returning capital to shareholders.

I’m not going to argue against the tax implications. Those are undeniably obvious.

I also do not want to dismiss the accretive value to growth in earnings (and other) per share metrics. I’m unabashedly bullish about buybacks in general.

However, I don’t think enough people think about the upper bounds of buybacks.

At a certain price point, particularly as a company’s stock trades at higher and higher valuations, stock buybacks begin to become value destructive.

You don’t need a DCF to understand this. Returns on capital from buybacks generally reduce as the valuation at purchase increases.

Those companies with high returns on capital are the ones most likely to trade at higher valuations.

And in this sense they are more crippled than their less successful peers.

But because buybacks reduce both shares outstanding AND invested capital, the insidious destruction of capital to shareholders from expensive buybacks is less obvious.

Any return of capital to shareholders, whether through dividends or stock buybacks, help a company keep its return on capital metrics propped up precisely because they reduce the capital base.

Blindly screaming for reinvestment, acquisitions, or buybacks at any price doesn’t fully consider Total Return for shareholders over the long term.

Each one of these factors play a role in demonstrating times where dividends should be preferred, but because they don’t make their way to financials in different ways, they don’t receive much attention.

And because the seeds of value destruction do not sprout until years down the line, hindsight bias will lead investors to blame some outside factor for a company’s eventual underperformance, rather than the underlying destruction of capital that occurred behind the scenes for years.

And because investors today abhor dividends, management’s only logic is to give what investors scream for—the capital destruction that only dividends could’ve saved.

The Morality of Dividends

You could forget about all of the intense business and accounting analysis which makes up my defense of dividends and instead conceptualize it in this way.

Unbridled greed is at the root of the general distaste for dividends.

It sounds paradoxical, but perhaps the titan John D. Rockefeller had his greed in check when he said,

“Do you know the only thing that gives me pleasure? It’s to see my dividends coming in.”

At the root of it, the payment of dividends is a moral obligation of companies.

Investors see dividends as unattractive because they perceive it as sacrificing future growth. Perhaps they don’t realize that their expectations are flawed. The great growth ship has already sailed.

Managements see dividends as waving the white flag on their abilities and ambitions.

But at what point do businesspeople say, “enough is enough”?

What is the endgame of business? Is it solely the pursuit of profits, with no regard for fellow man?

The ideas of the past don’t always serve well the realities of the future. At a certain point, businesspeople need to accept the responsibilities that come with success.

We hold politicians and tyrants to high moral standards. We expect them to make decisions for the wellbeing of society.

But why does the buck stop with the leaders of great businesses?

At a certain point, the top businesses which dominate the world’s markets need to recognize that at a certain point, you’ve made it. It’s time to give back. It’s time to smell the roses.

And for the greedy capitalists, that means enjoying the unexciting fruit of dividends.

Businesses which overextend themselves and destroy capital do no good to no one. Flexing huge muscles powered by flush coffins just to wreak havoc on steady markets only hurts all of the players, employees and investors—those who worked hard to build a strong moat just like you did.

And this winner-take-all, zero-sum mentality has a pervasive effect on society.

We’ve seen how an unrestrained pursuit of profits can do irrevocable damage to nature.

What about the effects of unlimited ambition within the biggest business empires we’ve ever seen?

It’s true we’ve seen big business before.

The Nifty-Fifty. Ma Bell. Standard Oil.

But have we ever seen businesses so big, growing at such high rates to make disruptors blush?

We all see how today’s technology has made things better, faster, easier.

But the seemingly unrestrained potential to growth could have dire consequences which we’ve never experienced yet.

Why let those lessons be painful ones?

Why not get ahead of the ball before it’s too late?

Big Tech and a New Dividend Theory

Facebook is throwing around narratives about building a metaverse, or one app to rule them all. Maybe they are seeing the writing of maturity on the wall. How much money are they willing to throw at a solution which might not generate even an inkling of consumer demand? What’s so wrong about at least starting a habit of giving back with dividends?

So, businesses… big businesses. Big tech businesses.

Stay in your lane. Reset the unreasonable expectations of investors in a strong bull market and pay a modest dividend.

Smell the roses. Both businesses and investors.

Spend more capital in giving back to society. Give investors liquidity through dividends so that they can donate and do the same. Pay a little in dividend taxes to drive prosperity elsewhere (if, IF, politicians can be good stewards too).

The anti-dividend rhetoric has potentially dreadful consequences if it continues to get louder.

From both a capital allocation, and moral, side.

As the world stands today, we need more dividends, not less. We need more investors advocating for a new theory about dividends. Moral dividends.

Unfortunately, as more money continues to be minted in crypto, NFTs, SPACs, and speculative IPOs, we seem to stray further and further from that light.

Related posts:

- Dividend Ratios Pt. 2: How to Identify Sustainable Dividend Growth As we discussed in part 1 of this dividend mini-series, there is much focus on the past dividend growth of a stock– yet this doesn’t...

- Dividend Ratios Pt. 3: Measuring a Stock’s True Dividend Payout Ratio Measuring how much a company is growing in size, and how much it has grown its dividend, is only one part to finding great dividend...

- Dividend Ratios Pt. 1: Evaluating the Dividend History of a Stock One of the most disturbing trends on Wall Street that I’ve noticed over the last 100 years is the movement away from an emphasis on...

- The Importance of Stocks with Dividends- Even Small Dividends One of the biggest hurdles to stock market investing is a mindset shift. Many beginners can’t get their heads around the reasons to buy stocks...