The term “Run Rate” is one that you quite possibly might have heard before, but many people do not know what it means. It is a term that frequently is said on shows like Shark Tank but also oftentimes used in the business world.

Essentially, run rate means that you’re taking the current market conditions for something and extrapolating them out over a future period of time to use as a predictor of what might happen. For instance, a younger company on Shark Tank might say that they’re losing money at a rate of $50K/month.

If they have $300K left in the bank, that would mean that they’re going to run out of money in six months at their current run rate, as $300K/$50K = 6 months.

Run rate can also be used for metrics such as revenues and earnings, and truthfully any other metric where people are looking for a short and simple way of predicting what the future might have in store.

Now, there are some issues, or risks, with using a run rate as the end all, be all for a company.

- It assumes market conditions will stay the same

- The timeframe for run rate can be skewed

- Product releases like iPhone

- One-time sales

Market Conditions Do Not Stay the Same

If anything, I think that this is something that we all learned during COVID. Market conditions are never stagnant and things are constantly changing. While a pandemic might not be something that is necessarily repeatable, per se, market conditions are still everchanging for companies.

For instance, new competitors may enter the market, acquisitions may take place, or potentially even major PR issues might occur with a company. For instance, I think about something with Peloton when they had their holiday ad that caused a lot of controversy and how their stock sold off drastically that day.

Some people might see that ad and have their opinions completely change about Peloton and no longer want to buy one and might even sell their current Peloton, therefore taking away a potential buyer from Peloton as they purchased in the used market vs. new.

A more “market-centric” example would be for oil & gas companies. As we constantly see shifts towards EV and higher-efficiency vehicles, a legitimate argument could be made that using a steady run rate to predict demand going forward would be a flawed argument.

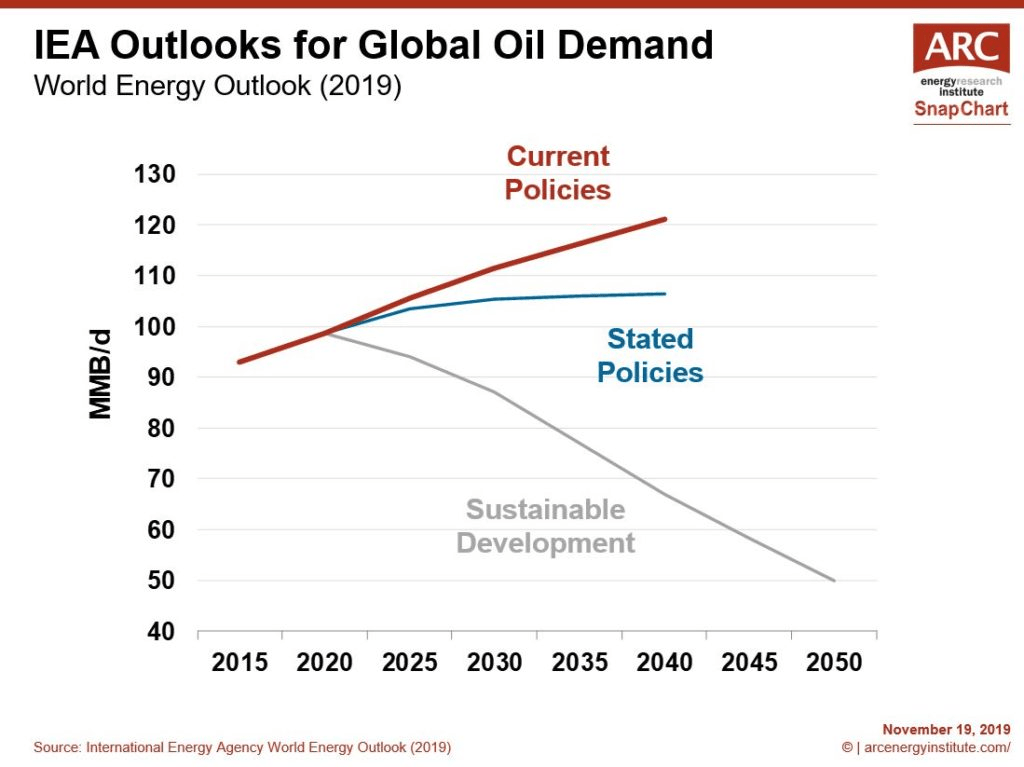

For instance, take a look at the chart below from the Arc Energy Institute:

Global oil demand is expected to increase over the next 30 years under the current policies, essentially remain flat with the stated policies of current leadership, and dramatically decrease with a sustainable development approach.

So – what sort of future estimates should the oil & gas industry use? Well, that’s up to them, but using a current run rate seems like they’re providing the most optimistic approach and not one that might be the most realistic.

The Timeframe for Run Rate Can Be Skewed

Typically when companies are using a run rate for future projections they’re looking at a very short-term timeframe in the past such as the most recent quarter. Well, that obviously can have some major problems.

If the company is a retailer and they use their holiday season then they’re going to be using inflated sales and assuming those will occur over the course of a year when in fact it’s limited to just a couple months of the year.

If Amazon were to use a time period that included their Prime Day then they’re obviously going to have an insane bump in that quarter for a couple days and it would be included in the run rate.

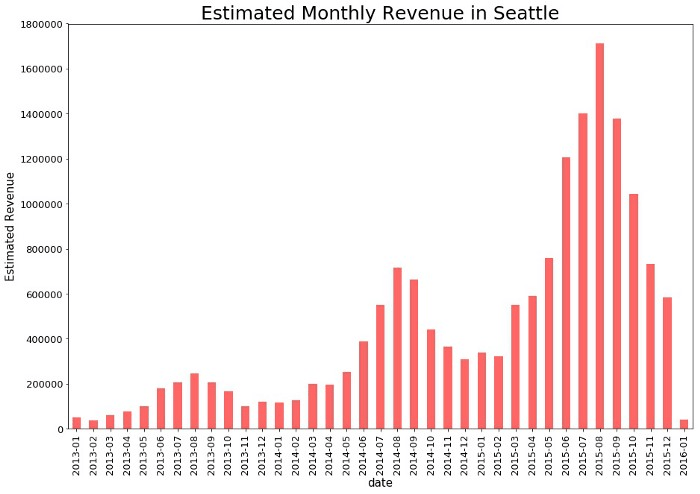

There was an extremely interesting article showing Airbnb sales in Seattle and the most profitable times for people to rent out their homes, and you can see below that the most profitable months are consistently in August:

To me, this shows that the supply/demand balance is the most skewed in August signaling that many people are looking to travel, potentially due to trying to cram in a last second vacation before kids go off to school. If Airbnb were to take this Q3 (July – Sep) and use those sales as their run rate to replicate an entire year, they’d be using a period of seasonality that simply is not representative of their entire market.

I don’t want to say it’s artificially inflated because it’s not, but if you were to take your three highest-demand months and use that as a repeatable baseline for demand over the course of a year, then it would be fake news.

Product Releases

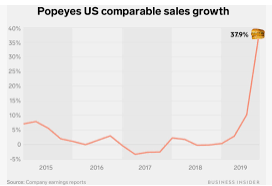

A product release is something that can have a massive impact on sales on a short-term basis as people are extremely excited for the new product. An example that immediately comes to mind for me is the Popeyes chicken sandwich.

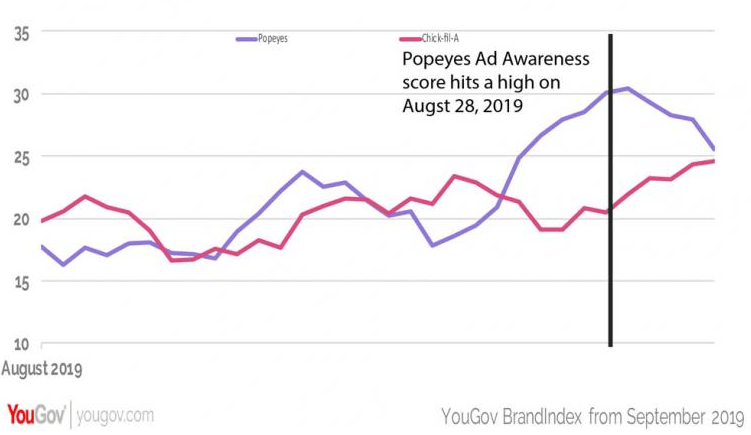

When that sandwich was introduced, the hype that it had was absolutely off the charts. People were losing their mind about it and the organic marketing that it had from people posting pictures and videos online drove the Ad Awareness for Popeyes to insane levels as you can see below:

You can see that the ad awareness was really right in line with Chick-fil-a and then it just ramped up to a new level above Chick-fil-a before quickly falling back in line.

Now, of course it’s a reasonable thought to assume that sales also followed and that the company saw a major uptick on that side as well, but likely just for a short-term.

We have seen many competitors come into the market with their own new chicken sandwiches including KFC, McDonalds, Buffalo Wild Wings and others, all seemingly trying to copy this sandwich that Popeyes has created. Popeyes was first, but may or may not be the best.

The fact of the matter is that they capitalized on this new product launch and really took over the chicken game for a short period, but now they seem to really just be back to being themselves – an average Chicken restaurant with a good sandwich.

If they were to take this quarter of massive growth and use that as their run rate, it would be very skewed. If they were to use this as their run rate to incentivize more marketing dollar spend, or even show that their marketing was working, it would be flawed.

It was really around just one product that had an amazing launch. Honestly maybe a better product launch to the public than I can ever remember. But that’s all the reason why it shouldn’t be used as a baseline for their run rate – it’s inflated!

Another example is anytime that Apple releases a new iPhone. When Apple releases their new iPhones, it’s like a freaking black friday deal is going on. People seem to absolutely lose their mind.

And while I am a huge fan of Apple and their iPhones, I do not fall prey to this, and instead I actually prefer that Apple pays me with their steadily increasing dividend.

But I think I am in the minority with this as I know many people will literally line up to get the newest phone despite a lot of times the phone seemingly being essentially the same as the most previous change, with a bit faster system and a bigger screen.

If Apple were to include these new product rollouts in their revenue run rate projections then they would be artificially increasing their projections as they realized higher revenues than typical during this new product launch.

One-Time Sales

The last major risk that I see with using run-rate is if someone was going to use a one-time sale in their projections. This might seem similar to the other examples that I have given, but I am more-so referring to if a company were to have been awarded a big contract that will inflate their numbers.

For instance, I think about a young company that is really working to get their foot in the door and latch onto some major customers. For instance, if a new EV company was working to get someone to order a lot of their vehicles and they finally got a fish on the hook, that would be a huge win for the company, right?

Say that they finally got their first order to take them from pre-revenue to actually having sales. Or, maybe they just went from having some small fish to capturing a new customer that was going to make up 25% of their revenue.

Again, amazing things for the company!

But if they took these growth rates and used them as their run rate baseline to imply that it was going to be repeatable to keep growing this way, it would be grossly misleading.

On the other hand, this can work in the exact way if a company were to lose a major customer. Let’s flash back to last year with an example from a cloud computing company that I like, Fastly.

Fastly, as many “newer” companies will do, had a large majority of their revenues concentrated on one customer – TikTok. TikTok accounted for 10.8% of their sales the first nine months of 2020 and you might recall a lot of political drama regarding TikTok during the 2020 election in the US.

Well, long story, short – it was bad news for Fastly to have so many eggs in the TikTok basket with all of this drama occurring.

So, what if Fastly were to take the last nine months of sales and use it as their run rate for future outlook? Well, they certainly can’t do that because they literally just lost 1/9 of their revenues due to political reasons.

On the other hand, do you think Fastly was going to simply just remove them and say, “hey this is our run rate going forward with 11% less revenue?” No!

Companies are always in the business of communications and saying things in a way that makes them always sound positive to investors and analysts. They’re well trained and have their PR teams aligned to make sure that they’re packaging everything to give a very rosy image and make things seem perfect.

The reason that I really am diving so far into the weeds on this is because I think it’s absolutely imperative that you do more than just listen to analyst opinions and management outlook on what the company is doing. Nobody is going to say, “hey, we sucked and lost a massive customer”.

I do want to be very clear here and say that I am not telling you that companies are going to intentionally mislead you. At the end of the day, any sort of guidance that the company gives is guidance that they’re going to be held to in the future.

If they mislead the analysts then they’re simply creating a messy bed that they eventually are going to have to lay in.

All that I am saying is that it’s imperative that you do your own research and come to your own conclusions. You should make sure to understand the ins and outs of the companies and form your own opinion about if that company is one that has a sustainable business model and is primed for many years of success.

This might sound overwhelming but it’s not. Start with a company that you already know some about, invest a little bit to get some “skin in the game”, and then just start to research a bit to understand the company.

Andrew, Dave and myself are all keen on reading a 10k before investing too much in a company, and it’s something that you should work to train yourself into. Don’t let the company dictate their run rate – you will then be able to decide for yourself what projections to use!

Sounds like too much work? It can be overwhelming at first, for sure. If you’re struggling to get started, head to the Sather Research eLetter. No better way to start your investing journey with your real money than following the same exact stocks that Andrew invests his real money in as well!

Related posts:

- “Knowing Your Numbers” Like the Sharks = Understanding Unit Economics Unit economics – what a boring topic amiright? No – I am not right. And chances are, you also agree that unit economics aren’t boring...

- Analyzing Greenblatt’s Magic Formula Strategy without Backtesting It seems that every argument supporting Joel Greenblatt’s magic formula examines some flavor of a backtest to prove its effectiveness. The problem with backtests is...

- Avoid Value Traps by Understanding Various Valuation Multiples by Industry! One of the hardest things to do when investing is figure out the proper value for a company. Sure, “buy low, sell high” sounds easy...

- Understanding Buffett’s Owner Earnings for Beginners As we continue to get more and more into the weeds with Warren Buffett in his book, ‘The Essays of Warren Buffett’, he focuses on...