Edited 3/24/2023

Accounting for stock based compensation expense can be tough. The numbers don’t always line up from the income statement to the cash flow statement.

Also, stock based compensation (SBC) is either automatically included or excluded, depending on which Free Cash Flow formula you are using (FCFF or FCFE).

Over the long term, the real SBC expense impact to FCF makes a big difference to compounding. We should understand this impact if we want to make good long term investments.

And, seemingly more and more technology companies are looking to attract top talent through stock options such as RSUs. The impact of SBC to the long term cash flow of a business may become increasingly important over time.

Let’s try and make this as simple as possible.

Here’s the structure for today [Click to Skip Ahead]:

- What is Stock Based Compensation Expense?

- How is SBC Calculated in a Company’s Financials?

- Why You Should NOT Add Stock Based Compensation back to FCF

- Issued, Vested, and Unvested Stock

- The Obvious Reason to Account for SBC

- Average Stock Based Compensation Percentage by Industry [S&P 500]

Hopefully after reading this post you will learn the exact ins-and-outs of stock based compensation. It should provide better clarity towards how you see company valuations.

What is Stock Based Compensation Expense?

First, we have to know that SBC is not something we can just ignore just because it is a “non-cash expense.”

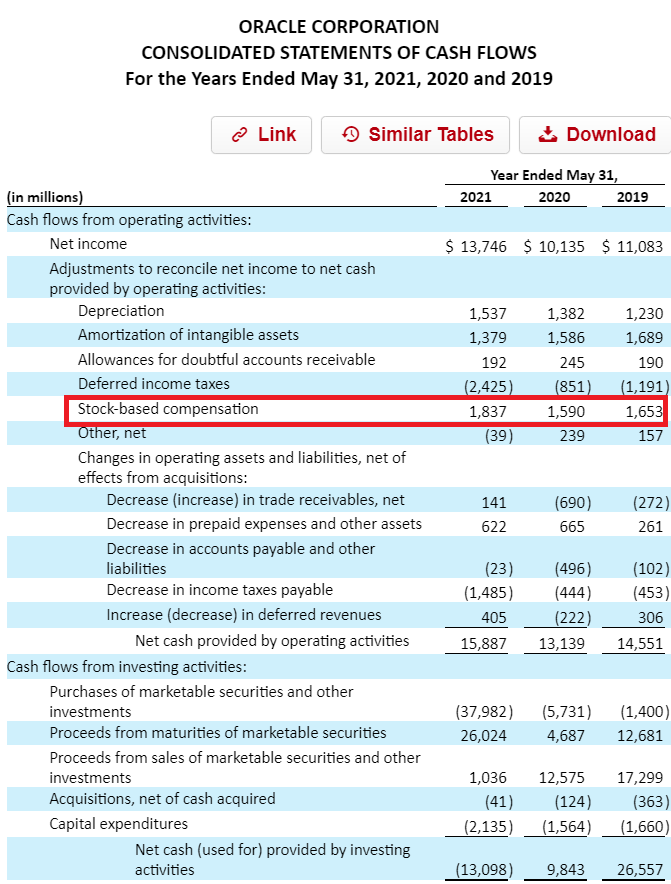

The fastest and simplest way to find stock based compensation expense for a company is in its cash flow statement, under the Cash from Operations section. Here’s an example from Oracle’s annual report:

You can see that stock based compensation is added to cash flow from operations, and because some analysts compute FCF using the cash flow from operations, it shows up as an addition to FCF.

This version of FCF should also be recognized as FCFE (free cash flow to equity), and is often simplified to:

FCFE = Cash Flow From Operations – Capital Expenditures

There’s a very good reason that non-cash expenses like Depreciation and Amortization, and Stock Based Compensation, are added to Net Income to create Cash Flow from Operations. It is because these expenses don’t represent literal cash coming from a business.

Non-cash “expense”: Depreciation

Remember that Depreciation expense is an accounting measurement. Its goal is to smooth out large capital investments in the income statement.

A company may very well have to burn significant cash flow in a given year to build a factory, for example. In the years to follow, there might be little in cash outlays for that plant. But from the income statement side, that cash outlay is spread as an expense over many years rather than just one.

The reason for this spreading out, or depreciation, is so the impact of a large investment doesn’t mis-represent the true earning power of a business.

Non-cash “expense”: Stock-Based Compensation

Stock based compensation expense is similar but different. A company can issue shares to pay its employees as bonus compensation, and this does not come out of cash from the business.

Instead, shareholders are essentially footing the bill to compensate employees inside the company. Often, SBC doesn’t make up a big portion of FCFE, and so its dilution effect to shareholders is generally close to nil.

And, many stock options which are granted/vested will be accounted for in (diluted) shares outstanding. Which is why there are basic shares outstanding and diluted shares outstanding formulas. We recognize those as used to calculate basic EPS and diluted EPS, respectively.

The sticky part about SBC is that certain stock options will be accounted for in diluted shares outstanding while certain other ones won’t.

Depending on the company, this can make a big difference in dilution to shareholders, which affects the real cash flows available to shareholders over the long term, and can affect total return.

As the great Warren Buffett once said about SBC:

If options aren’t a form of compensation, what are they? If compensation isn’t an expense, what is it? And if expenses should not go into the calculation of earnings, where in the world should they go?

Warren Buffett

How is SBC Calculated in a Company’s Financials?

Warren Buffett’s great quote occurred during a time when the idea of adding stock compensation as an expense to the income statement was being debated.

Today, that controversy is largely over, and we have some effects to financial statements from it.

Here’s how SBC shows up in a company’s financials today.

- Income statement

- Cash flow statement

The bottom line is that you should see stock based compensation expensed in a company’s income statement, as a part of the calculation for Gross Profit or Operating Profit. Then, it is added back to the Cash Flow Statement under Cash From Operations like we discovered above.

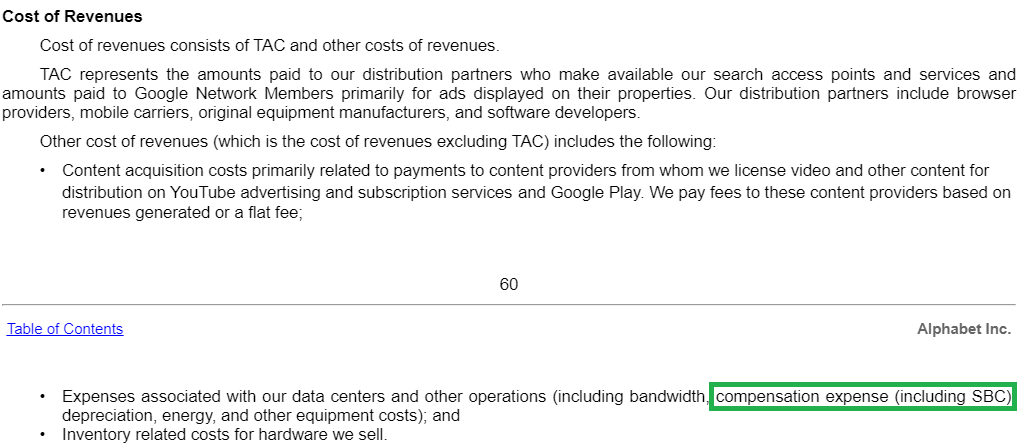

Take Google as an example. Here’s a quote from their 10-K, explaining how they account for stock based compensation:

This tells us that the company includes SBC in their income statement as part of Cost of Revenues (also called “Cost of Goods” with other companies). This means it will affect Gross Profit and Gross Margin.

We can also observe that Stock-Based Compensation gets its own section in the 10-K. Google states that the expense (for RSUs) is recognized using the “straight-line attribution method.” They also provide additional information on PSUs.

If you’re unclear on some of the basic forms of SBC’s, such as RSUs and PSUs, I’d highly recommend Dave’s post on locating share based compensation in the 10-K. It’s a really great introduction to this whole topic.

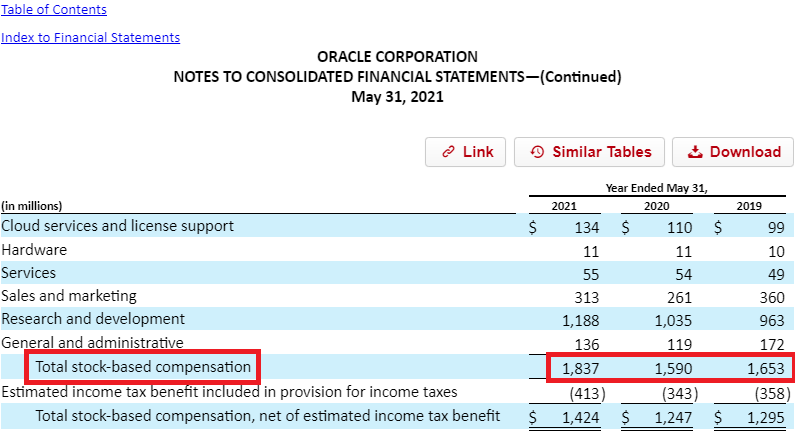

Going back to Oracle, they also provide interesting details on their SBC expense through the notes to the financials. In there, the company breaks it down by operational category:

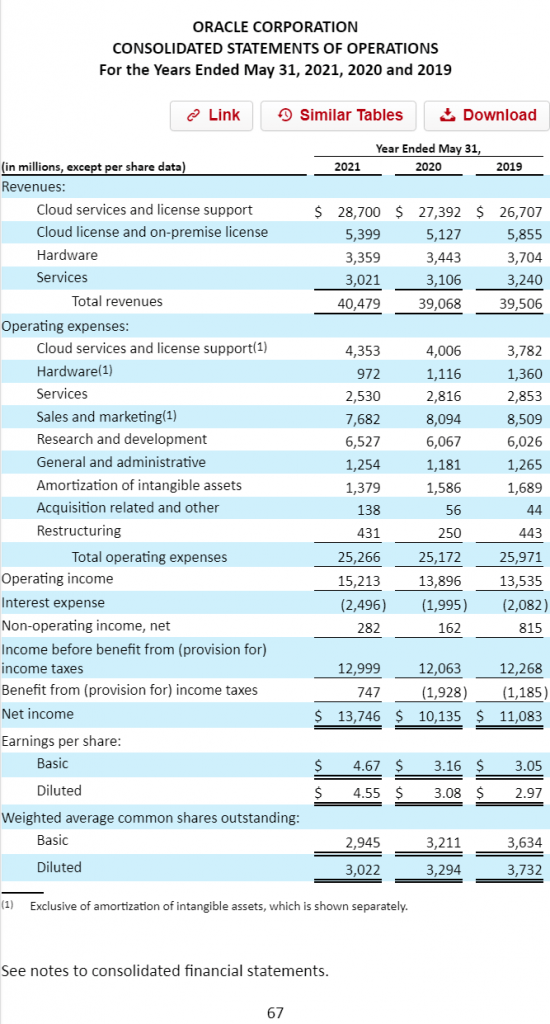

Checking with the way that the company reports its income statement, we can see why they’ve classified it like that:

That these SBC expenses are included in R&D and SG&A implies that some of their Stock Based Compensation expense is part of Operating Expenses rather than only Cost of Revenues or COGs (like Google’s was).

It shows that there’s probably some flexibility on how companies choose to report SBC for GAAP purposes.

Again, though calculated as an expense in the income statement, SBC does not describe “real cash” from a business. Therefore, it gets added back in the cash flow statement.

These two statements, the income statement and cash flow statement, should reconcile from year-to-year, in theory. But, many companies won’t disclose SBC as a line-item on the income statement, which makes it hard to double check.

Why You Should NOT Add Stock Based Compensation back to FCF

Returning back to the financials, the reason that stock based compensation can often be forgotten is because it can often get lost with the other moving pieces of the cash flow statement.

However, just because the direct cash effect of SBC is vague doesn’t mean it’s non-existent.

This fantastic post by a writer from Wall Street Prep argues that point, stating:

Investment bankers and stock analysts routinely add back the non-cash SBC expense to net income when forecasting FCFs so no cost is ever recognized in the DCF for future option and restricted stock grants. This is quite problematic for companies that have significant SBC, because a company that issues SBC is diluting its existing owners.

Professor of Valuation Aswath Damodaran also teaches that this real cost to shareholders should be reflected in a valuation model. He believes that SBC should NOT be added to Net Income in order to reach FCFE.

In other words, SBC expense should be subtracted from Cash From Operations when calculating FCFE from the Cash Flow Statement.

However, you don’t have to do anything with SBC expense when calculating FCFF (great guide about the FCFF formula here).

The reason why you don’t have to worry about stock based compensation expense in a FCFF calculation is because, remember; it is already included in the income statement.

Recall the Google and Oracle examples; one company had SBC expense as part of Cost of Revenues and the other as part of operating expenses. Since FCFF is generally calculated by starting with Operating Income and moving to NOPAT, the FCFF formula will account for SBC expense, all through Operating Income.

Issued, Vested, and Unvested Stock

Not all of the SBC expense in the cash flow statement represents the total potential dilution to shareholders.

There are several categories of stock options/RSUs/stock compensation at any given time:

- Stocks issued (this year) but not yet vested

- Stocks issued (this year) and vested, but not yet granted

- Stocks issued (this year), vested, and granted

- Stocks issued (previous years) but not yet vested

- Stocks issued (previous years), and vested, but not yet granted

- Stocks issued (previous years), vested, and granted

I’ll be frank. This stuff is above me at this time.

According Wall Street Prep, SBC expense in the cash flow statement represents stocks issued. It will be reflected (as potential dilution) in the future. Additionally, footnotes to the financials should disclose the number of shares that are granted, issued, vested or unvested.

In theory, you should include those additionally issued stocks which aren’t already included in diluted EPS into shares outstanding for FCF.

In practice it can be difficult.

From what I’ve seen, companies tend to expense SBC over a straight line, implying a spreading out of the expense over multiple years. Because you have a constant stream of old stock options and newly issued stock options, all expensed and/or diluted at different times, it can get messy.

It can be difficult, if not impossible, to “check your work” because of this factor, among others. So you might not want to include these classifications in your valuations.

The Obvious Reason to Account for SBC

That said, I don’t think there’s much of a sound argument for not subtracting SBC from FCFE.

True — there is not a “real” cash draw from the operations of a business when it issues stock as an incentive for employees. It’s doubly true if it takes multiple years to vest.

However, shareholders are paying for it out of free cash flows one way or the other.

Though it might not take “real cash” from operations, it most certainly must take “real cash” from financing activities.

Because some companies do massive stock buybacks, you might not see the impacts of the dilution of SBC expense to shares outstanding. The amount of stock bought back can be so much greater than that issued for employee bonuses.

And a company’s stock price can fluctuate between when they buyback shares and issue them, making the actual “cash drain” better or worse.

Regardless of where stock based compensation expense comes out from, whether through an increase in diluted shares outstanding or through cash spent in financing activities to buyback those shares, those are real dilutions to shareholders. It represents real cash obligations that never make it back to the owners.

In other words, SBC expense represents cash that is not really “Free Cash Flow,” defined as the stream of cash attributable to shareholders.

Whether you’re trying to mitigate the effect of SBC expense as it has caused dilution now or is likely to cause in the future, having some method to account for it in a free cash flow estimate should be a priority, especially for companies with larger percentages of stock based compensation expense compared to its Cash From Operations.

Average Stock Based Compensation Percentage by Industry [S&P 500]

I’ve included some data on the average SBC expense percentage compared to Cash From Operations for the S&P 500 over the last 10 years, from 2012-2021.

Here are charts showing both the averages for the entire market by year, and by sector:

| S&P 500 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE | 9% | 7% | 6% | 7% | 66% | 7% | 6% | 9% | 95% | 4% |

| MEDIAN | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% |

Note that like my other historical datasets, for ease of research this includes only the current constituents of the S&P 500 and not past ones who have dropped off.

| SECTOR | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Services | 18% | 8% | 8% | 7% | 10% | 10% | 13% | 71% | 1877% | -12% |

| Consumer Discretionary | 11% | 10% | 5% | 7% | -9% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 6% | 5% |

| Consumer Staples | 4% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 4% |

| Energy | 1% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 2% |

| Financials | 7% | 6% | 5% | 4% | 5% | 8% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Health Care | 9% | 4% | 7% | 9% | 20% | 13% | 11% | 14% | 27% | 3% |

| Industrials | 6% | 10% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 4% | 8% | 6% |

| Information Technology | 18% | 12% | 14% | 23% | 405% | 14% | 12% | 12% | 1% | 12% |

| Materials | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% |

| Real Estate | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Utilities | 0% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| TOTAL (AVG) | 9% | 7% | 6% | 7% | 66% | 7% | 6% | 9% | 95% | 4% |

It seems that the sweet spot for “SBC expense/Cash from operations” has been 4% (median). At its current pace, it is not appreciating enough to be a noticeable trend, which I found surprising.

If a company you’re investigating is much higher than this 4% mark, then the dilutive effect of SBC expense should be more closely examined. Period.

Andrew Sather

Andrew has always believed that average investors have so much potential to build wealth, through the power of patience, a long-term mindset, and compound interest.

Related posts:

- Share Based Compensation Expense – How to Locate it in the 10-k Today, share-based compensation issued to employees continues as one of the more disruptive finance topics, and some C-suite managers have abused their positions. Those behaviors...

- Basic Cash Flow Statement Breakdown (by Each Component) Updated 4/21/2023 Cash is king, and finding companies that generate cash is the holy grail of investing. The basic cash flow statement provides answers to...

- Simple Income Statement Structure Breakdown (by Each Component) Updated 8/7/2023 The income statement is the first of the big three financial documents that all public companies must file. But what do we know...

- Depreciation Expense: How to Decode Updated 8/7/2023 Depreciation is an accounting term that has a big impact on a company’s future profitability. It is a controversial topic because, as Warren...