Provision for Income Taxes is a line item in a company’s Income Statement which tells investors how much a company pays in taxes for a given Fiscal Year.

By looking closer in a company’s Notes to Financials, the investor can get clarity on additional details of the Provision for Income Taxes—such as which amount is attributed to U.S. Federal and State taxes, and Foreign Taxes.

Understanding and finding the Provision for Income Taxes in a company’s financial statements is an easy task; the fluctuations of those values is much more complex.

The timing and amount of Income Taxes can vary widely due to:

- Tax credits available

- The geographical split of profits

- When taxes are deferred or recognized

- Changing tax laws

When you get into the changes in cash flow for taxes, these can also vary from the Provision for Income Taxes found in the Income Statement due to the timing in deferred taxes, and any back or forward taxes.

Understanding a corporation’s income taxes is really a wormhole and mouthful, and can require tax experts with years of experience. We should be clear I’m not a tax expert and am not fully attuned with every detail of the modern tax code. This research is based on other blogs and real company financial statements.

That said, as investors we should know the basics of corporate taxes.

If we can decipher the basics of interpreting Provision for Income Taxes and how they affect a company’s effective tax rate, this helps us model Free Cash Flow and Earnings. This is especially relevant for “multinational corporations” with significant amounts of profits and revenues earned outside the U.S.

In today’s post, we will discuss:

- Provision for Income Taxes Example: Amazon

- Provision for Income Taxes Example: Facebook

- Corporate Tax Implications of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)

- Two Ways Companies Are Currently Handling TCJA

Let’s start with a simple company’s financial statements: Amazon.

All of these examples will use a company’s latest 10-k, which I like to use bamsec.com to pull up, but you can also find at sec.gov.

Provision for Income Taxes Example: Amazon

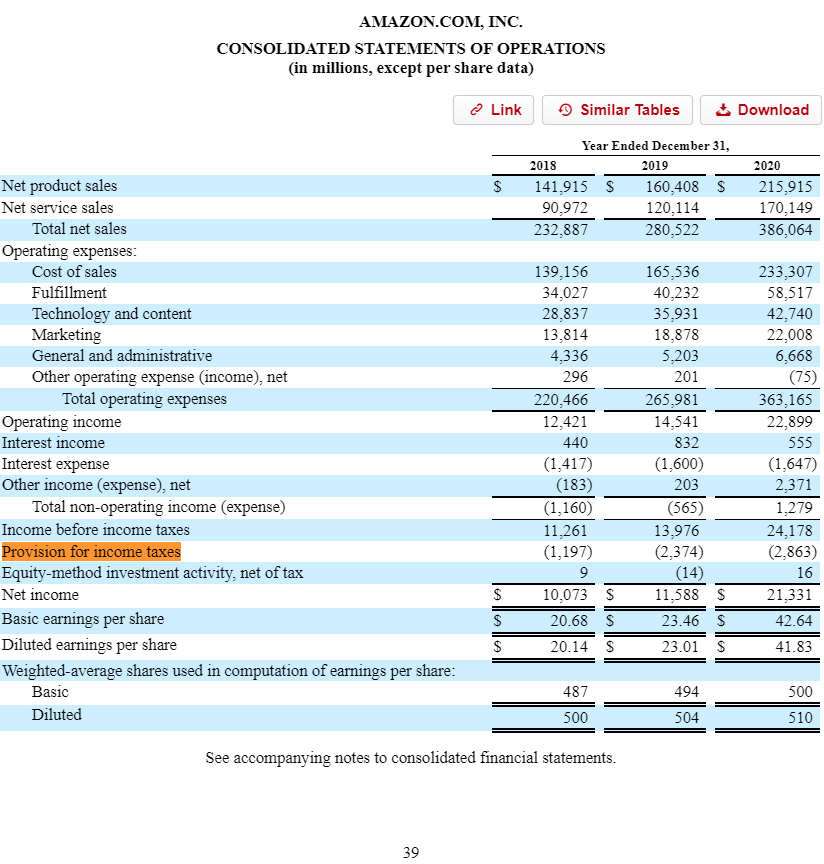

Using the “ctrl+f” search function for “Provision for Income Taxes”, we can quickly see the metric disclosed directly in Amazon’s Income Statement:

We can see the company has deducted the following for taxes in each fiscal year (in millions)

- 2020: $2,863

- 2019: $2,374

- 2018: $1,197

Using this data we can calculate the company’s effective tax rate, which is the ratio between Provision for income taxes divided by Income before income taxes:

- 2020 Effective Tax Rate = $2,863 / $24,178

- 2020 Effective Tax Rate = 11.8%

- 2019 Effective Tax Rate = $2,374 / $13,976

- 2019 Effective Tax Rate = 17.0%

- 2018 Effective Tax Rate = $1,197 / $11,261

- 2018 Effective Tax Rate = 10.6%

If we were to model the company’s tax rate for a FCFF Discounted Cash Flow model, or to project future Net Income from Operating Income, it would make sense to use an average of 3 years or 5 years of the company’s effective tax rate to make that estimate.

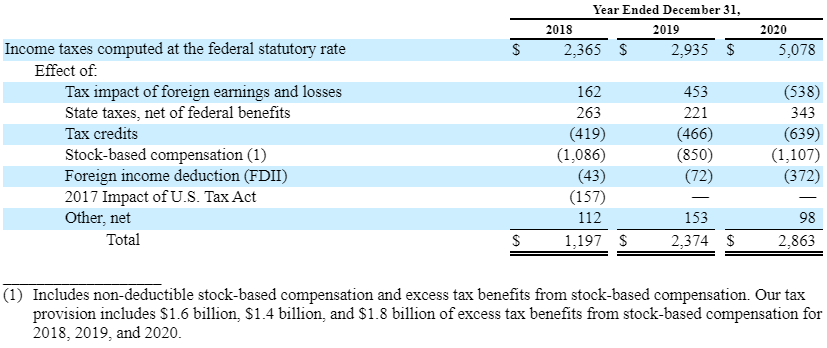

You may notice that the effective tax rates for Amazon in this time period is much lower than the current U.S. Federal Corporate Tax Rate of 21%, as well as lower than the combined U.S. Federal and State taxes that U.S.-only businesses are subject to.

This is because the company earns a significant portion of their revenues and profits overseas. Examining the Provision for Income Taxes further shows us the extent of that.

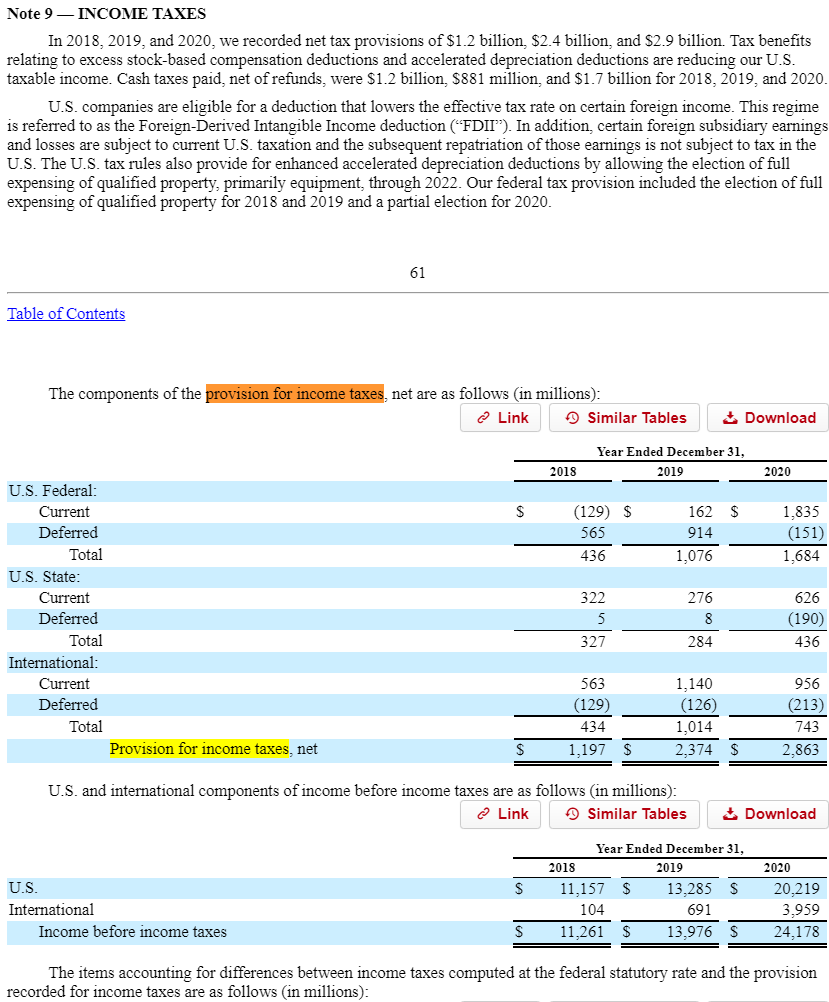

Continuing to scroll through the instances of Provision for Income Taxes using our handy “ctrl+f”, we can find the footnote for INCOME TAXES as follows:

And in additional detail:

We can see in the first screenshot the components of income tax provision that are both current and deferred for each aspect of taxes: U.S. Federal, U.S. State, and International.

Some taxes are deferred and some are expensed in the current fiscal year based on a variety of factors, which as the company explains in their 10-k can include:

“Our effective tax rates could be affected by numerous factors, such as changes in our business operations, acquisitions, investments, entry into new businesses and geographies, intercompany transactions, the relative amount of our foreign earnings, including earnings being lower than anticipated in jurisdictions where we have lower statutory rates and higher than anticipated in jurisdictions where we have higher statutory rates, losses incurred in jurisdictions for which we are not able to realize related tax benefits, the applicability of special tax regimes, changes in foreign currency exchange rates, changes in our stock price, changes to our forecasts of income and loss and the mix of jurisdictions to which they relate, changes in our deferred tax assets and liabilities and their valuation, changes in the laws, regulations, administrative practices, principles, and interpretations related to tax, including changes to the global tax framework, competition, and other laws and accounting rules in various jurisdictions. In addition, a number of countries have enacted or are actively pursuing changes to their tax laws applicable to corporate multinationals.”

I’d say that calculating or estimating all of the various factors and their impacts to income taxes would be basically impossible for almost all investors.

That said, just even considering Effective Tax Rate and its differences between companies based on their revenue locations could provide you with great advantages towards understanding the likely trends of future growth, earnings, and cash flows.

This is especially true if you are investing in companies with substantial revenues and profits abroad, and especially in times like today when international tax laws are being debated and potentially changed.

We will focus on that aspect next, with another multinational corporation as an example: Facebook.

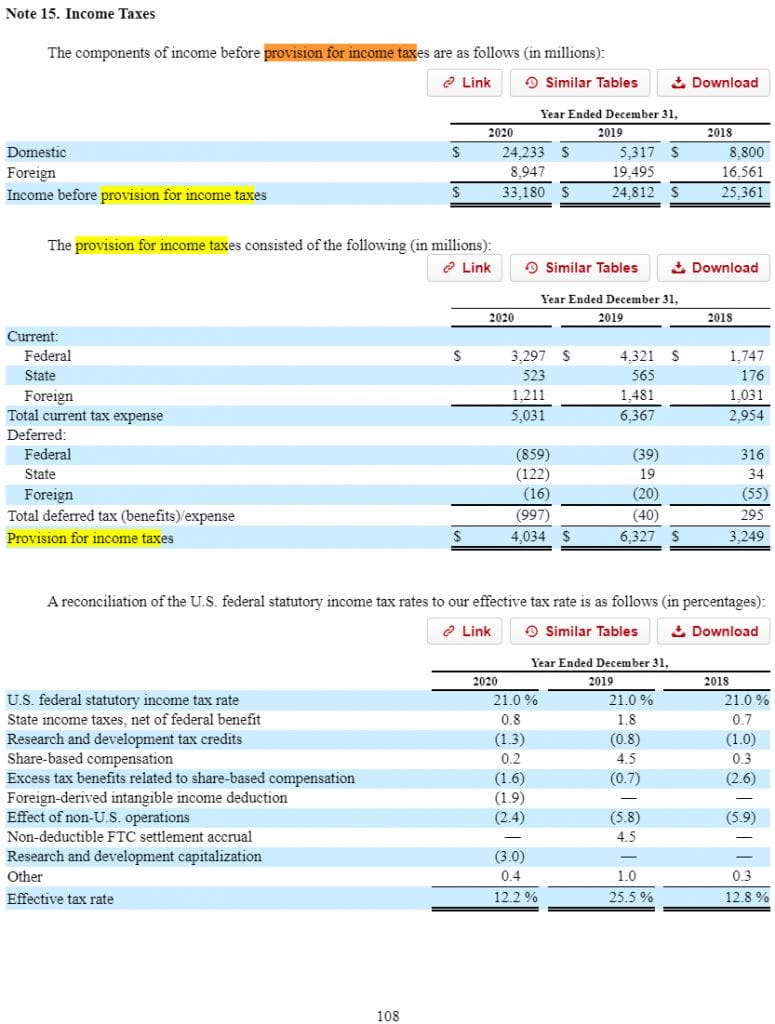

Provision for Income Taxes Example: Facebook

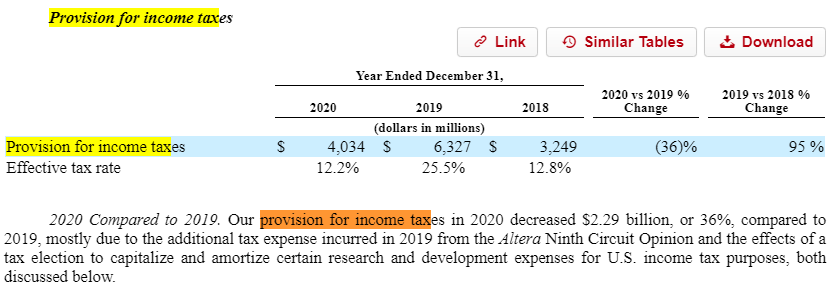

Using “ctrl+f” again to search for “Provision for Income Taxes”, we can see that in Facebook’s case they include a section which automatically calculates the Effective tax rate of the company for us:

Let’s dig further to find the footnotes on Income Taxes.

The company includes a similar breakdown as Amazon did, but also included in the first table a breakdown between what percentage of profits came from Domestic vs abroad in each fiscal year:

The percentage change impact of various line-items on the company’s effective tax rate as seen in the 3rd table is also a table that’s pretty common among various company 10-k’s.

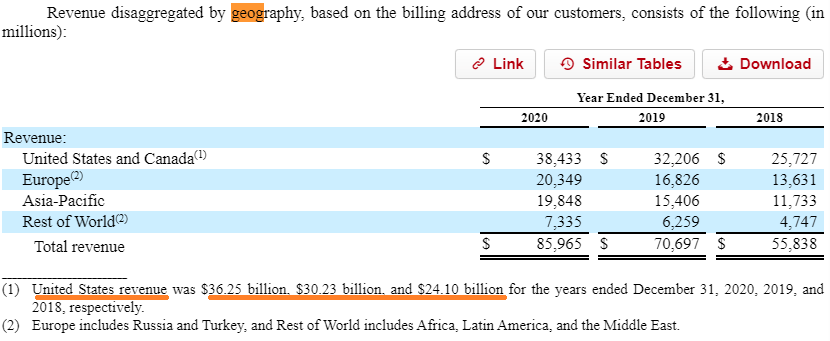

Here’s a table showing the differing geographies that represent Facebook’s revenues:

We can see that in 2020, for example, U.S. revenue made up about 42% of total company revenues.

But contrast that to the components of income before provision for income taxes again, in the table above:

- 2020

- Domestic = $24,233

- Foreign = $8,947

- Total EBT = $33,180

So while only 42% of revenues for the year came from the U.S., fully 73% of income before taxes came from the U.S.

It makes you wonder if the company is heavily reinvesting those foreign revenues into growth, or if U.S. users are simply more profitable than their foreign counterparts.

The actual taxes provisioned by Facebook are low for 2020, but 3% came from R&D capitalization, and 2.4% is related to the lower tax rates internationally.

To understand how international taxes affect U.S. multinationals, it might be beneficial to go back to Amazon’s financial statements as well as the history of foreign corporate tax.

Corporate Tax Implications of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)

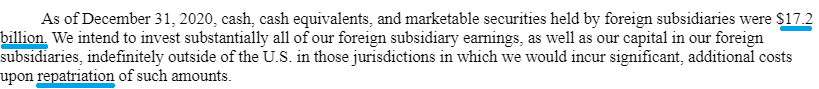

There’s a little blurb in Amazon’s 10-k, inside of their Critical Accounting Judgments regarding Income Taxes, where the company states their strategy towards international taxes:

It’s repatriation which is the magic word which was previously a huge problem to politicians, because it was a way for U.S. multinationals to effectively escape U.S. Federal Taxes.

To try and explain it in layman’s terms—before the TCJA (the 2016 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) there was a loophole in U.S. international taxes which stated that U.S. companies did not have to pay corporate taxes on profits earned abroad unless they were repatriated, i.e. brought back into the United States.

If foreign profits were instead reinvested abroad rather than repatriated, then companies could defer U.S. taxes on these.

As explained brilliantly in this post back in 2014, companies found a way around the repatriation problem by using corporate debt and other means to effectively access the cash that was not repatriated while still deferring the tax on them indefinitely.

The TCJA tried to fix this loophole by requiring companies to take a huge one-hit Income tax provision on all previously accumulated foreign earnings which were not repatriated.

This caused companies like Apple, Google, and Cisco to temporarily report extremely low earnings in 2016, 2017, or 2018 because they had to pay this one-time repatriation tax, on which the actual cash payments could be spread out over many years.

International taxes can be tricky, not only because they change, but also because depending on the scenario (and which country’s policy you are talking about), they can be charged based on:

- Where goods and services are produced (territorial)

- Where a company is headquartered (residence-based)

- Where goods and services are sold (destination-based)

As the Tax Foundation explained, the new TCJA has aspects of all 3.

As it relates to the repatriation issue, here’s how they outlined several of the new tax considerations for foreign earnings.

Let me also try to explain these in layman terms:

- Participation exemption

- Foreign profits sent back to U.S. (repatriated) are exempt from U.S. tax (but must pay foreign corporate taxes)

- Capital gains in securities inside foreign subsidiaries do not get this exemption

- GILTI, or Global Intangible Low Tax Income

- Certain percent of excess profits (ROI on foreign assets) are taxed by U.S. but generally at a lower effective tax rate due to deductions

- FDII, or Foreign Derived Intangible Income

- Certain percent of excess profits (ROI on intellectual property used as an export) are taxed by U.S. but generally at a lower effective tax rate due to deductions

- BEAT, or The Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax

- Effectively a minimum tax on multinationals with $500m+ in gross receipts

- Limits what expenses can be deducted for taxes when making payments to foreign-based companies

The combinations of these new laws are supposed to close the former loopholes around repatriation which were seen to be abused before TCJA.

It is also supposed to provide additional U.S. tax revenue to the Federal Government through the GILTI and FDII requirements, while also disincentivizing massive outflows of intangible assets (and IP) to foreign countries to take advantage of lower international Provision for Income Tax outcomes.

The Tax Foundation summarizes this effect brilliantly:

“Under the taxation of GILTI and FDII, U.S.-based multinational companies face roughly the same tax rate on intangibles used in serving foreign markets regardless of where those intangibles are located. If intellectual property is located in a foreign market and is used to sell products to foreign customers, it faces a minimum tax rate of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent through GILTI. If that same intellectual property is located in the United States and is used to sell products to those same foreign customers, it faces a tax rate of 13.125 percent through FDII.”

As you read through different company 10-k’s with significant profits from international operations, you’ll likely see references to GILTI and/or FDII, and how the company is reacting to each.

It is not the investor’s job to make these decisions for the company; rather it’s to observe what the company is doing, how that action affects Provision for Income Taxes, and if there’s anything down the pike which could permanently alter Effective Tax Rates moving forward (and then adjusting your models accordingly).

Two Ways Companies Are Handling TCJA

1—One strategy is to locate manufacturing and distribution facilities in Ireland, where the corporate tax rate is currently 12.5%. You’ll see many of the big multinationals using this strategy, as they’ll often disclose in their annual reports.

These foreign profits will be taxed by the foreign government but not the U.S. when “repatriated”, but because Ireland’s is much lower than the U.S. corporate tax rate, the effective tax rate comes out to be much lower for the company.

While they might not pay exactly 12.5% on foreign earnings due to other factors (like GILTI or FDII), the final Provision for Income Taxes comes out to be lower on these foreign profits rather than profits earned domestically, which has a noticeable impact to earnings and free cash flows.

2—Another strategy is to simply continue to reinvest foreign earnings abroad instead of repatriating, as we saw with the Amazon example.

In this case, a company would still be subject to FDII or GILTI, but might see the benefits of reinvesting internationally as outweighing any costs through Provision to Income Taxes which are now required because of TCJA.

Investor Takeaway

The nuts and bolts of Provision for Income Taxes can get messy, especially when you throw international taxes into the mix.

That said, understanding corporate taxes and their general effect on earnings and cash flows is a very worthwhile attempt.

Hopefully by getting a good sense of where these metrics can be found in a company’s 10-k, and what some of the jargon means around foreign taxes and TCJA deductions/credits, you can get a better sense of how a company’s Effective Tax Rate has been influenced and where it could go in the future.

Related posts:

- Simple Income Statement Structure Breakdown (by Each Component) Updated 8/7/2023 The income statement is the first of the big three financial documents that all public companies must file. But what do we know...

- Operating Leverage Formula: How to Calculate It with the Income Statement Updated 9/3/2023 “For a fundamental investor, anticipating revisions in expectations is the key to generating attractive returns. Sources of those revisions include fundamental outcomes (typically...

- Other Comprehensive Income, OCI, AOCI: The Basics, with 10-K Examples Edited for clarity: 9/21/22 As a company creates income, this changes its shareholder’s equity. Add investment securities and it can get hairy. The Statement of...

- Deferred Income Tax Liabilities Explained (Real-Life Example in a 10-k) Deferred income taxes in a company’s consolidated balance sheet and cash flow statement is an easy concept in principle, but when deferred income tax liabilities...